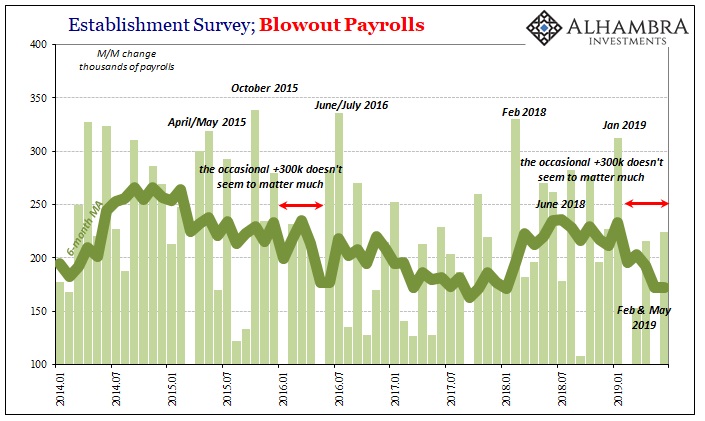

It’s never about a single payroll report. Even still, there’s something significant in how the “good” ones aren’t measuring up the way they used to. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the US economy gained 224k payrolls in the month of June 2019. Well above consensus, the headline is being described as relieving some of the growing economic anxiety.

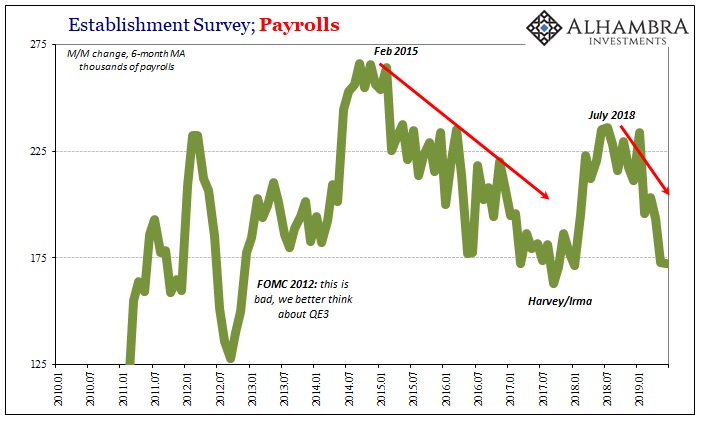

Set aside 224k being anything like good in a wider historical context, it doesn’t even stack up for recent times. Last year, for example, from February to August the monthly payroll change beat 250k in four out of those seven months. This year, dating back to January’s “blowout” above 300k, that hasn’t happened even once during the latest five months.

That’s a meaningfully long time to go without something better. The last time this happened was just prior the 2017 hurricanes when the labor market was bottoming out from Euro$ #3. It also happened during the first five months of 2016 – coincident to the worst overall economic conditions of that period.

When there are more frequent bad months, as in February and May, interspersed with less good good months, the overall message is not one for relief. The labor market, like the economy, is clearly in a slowdown mode.

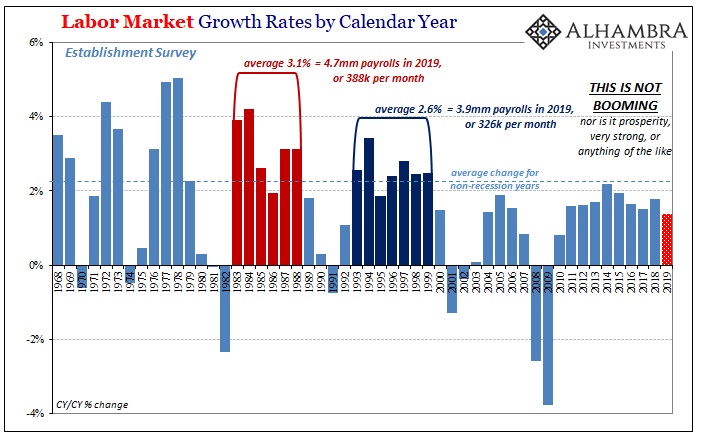

Including June’s estimate, this year remains on track to be the worst one since 2010. The lowest out of continuously subpar growth isn’t a foundation from which the domestic system might avoid all this growing “overseas turmoil.” Rather, what the labor market shows is that the October-December landmine absolutely struck the US economy, too.

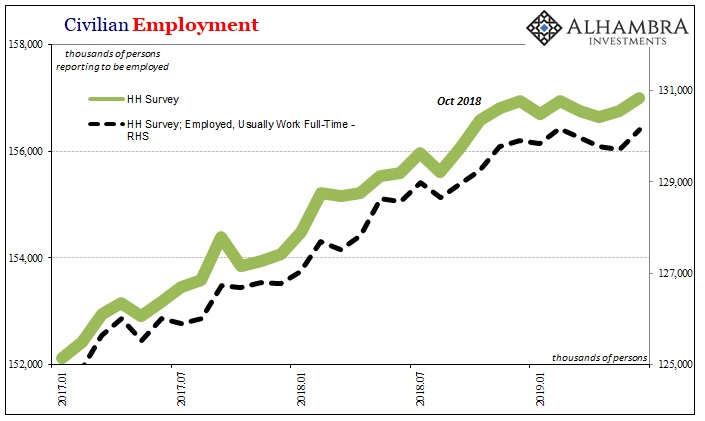

Payrolls and jobs are at best coincident indications if not in more extreme situations lagging. Besides the downshift in the Establishment Survey, the Household Survey has pretty much flatlined – and June was a bounce back month in this alternate view, too.

Factoring the 247k increase in the number of persons reporting to be employed in the Household Survey during June, employment growth since last November is just +202k total. Those reporting having worked on a full-time basis rebounded last month as well, but that number is also barely above November’s.

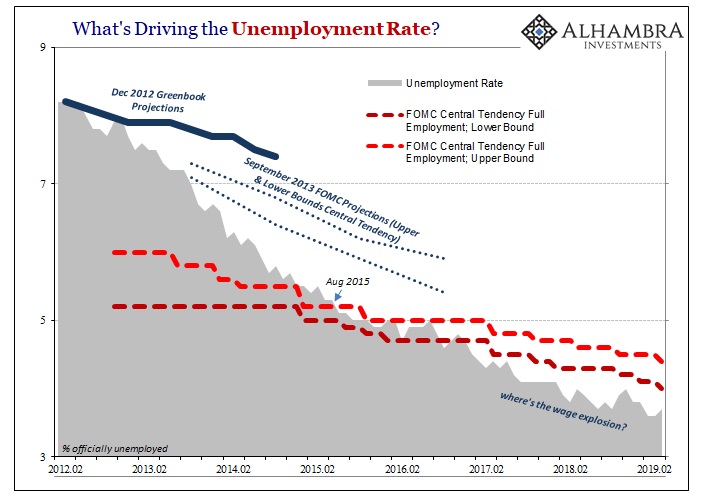

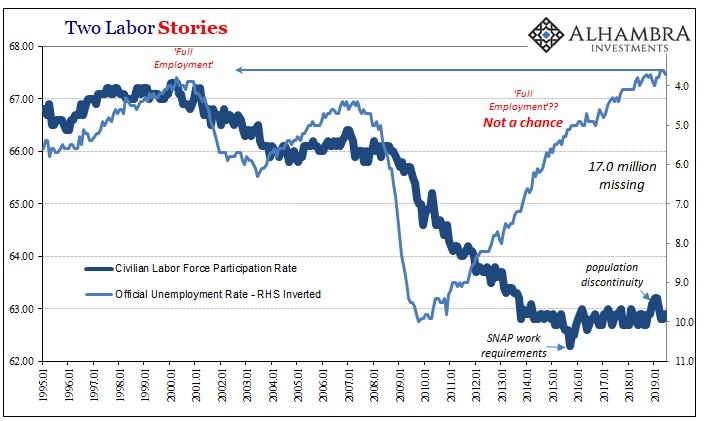

The unemployment rate ticked up to 3.7% since the labor force like the other data points rebounded slightly in June. Even so, for the entire year so far, halfway through, there are a quarter million fewer Americans in it.

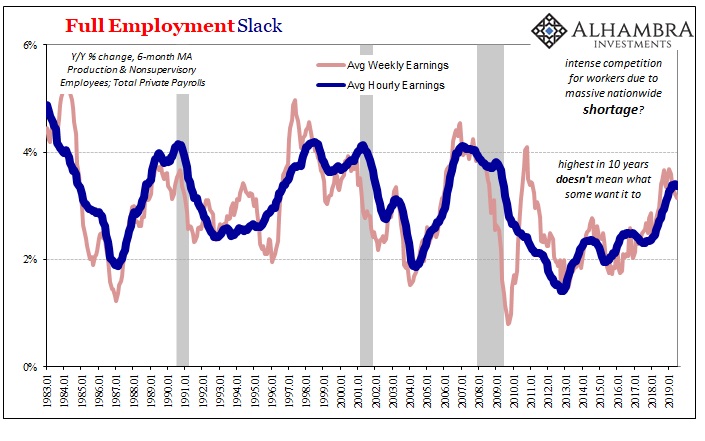

Economic or macro “slack” had been unusually high to begin with, this building slowdown seems to have added back to the pool. Wage growth which had been accelerating (but still well short of a shortage or even tight labor market) has stopped (second derivative) this year. Wages are still growing, no longer at a quickening pace.

In fact, average hourly earnings growth peaked…in December 2018. At 3.5%, it was both the highest in a decade as well as significantly less than what is supposed to happen at or more than “full employment.”

Ever since December, wage growth is stuck at around 3.35% – including June’s increase at exactly that rate.

None of this is sexy enough for our either/or mainstream. Economics only gives us a choice between boom and recession. Unless there is a minus sign, which is what many are waiting for, the boom must have continued. A slowdown, even one showing up right now at this time, doesn’t factor in the overriding narrative the way it should.

The labor market is already weak and for what is shaping up to be a prolonged period – not just a month or two, a decelerating trend remains in place. All the indications post-landmine suggest this is just getting started. American businesses may not yet be laying off workers by the tens or hundreds of thousands, but the chances something like that happens hasn’t been diminished by the June numbers.

If anything, the probability has increased. The month-to-month fluctuations don’t matter; they aren’t meaningful (and barely qualify as statistically significant, and even then only at a 90% confidence). A slowing labor market means the consumer won’t be able to bail out the economy moving forward. More than that, it shows the landmine was real, global, and substantial.

Therefore, unless something meaningful changes before too much longer the chances of a break (minus signs in the labor market) only rise. And this monthly report removes the labor market from the list of possible things which might have been able to do it.

Stay In Touch