Gordon E. Moore had co-founded Intel and so he had unique insight into the growing computer world. The revolution required a lot more (pardon the pun) computing power, which, Moore surmised, wouldn’t be too difficult to deliver. In 1965, he had observed that innovations were leading firms like his to be able to install double the number of transistors on silicon chips every two years (later estimates said 18 months).

Not only that, the price of computers would fall by about half in around the same time. Efficiency.

Our digital age first needed what came to be known as Moore’s Law because the size of silicon chips is limited. Processors had to get better, to be able to do a whole lot more in pretty much the same amount of space.

What does that have to do with sponsored repo? What is sponsored repo?

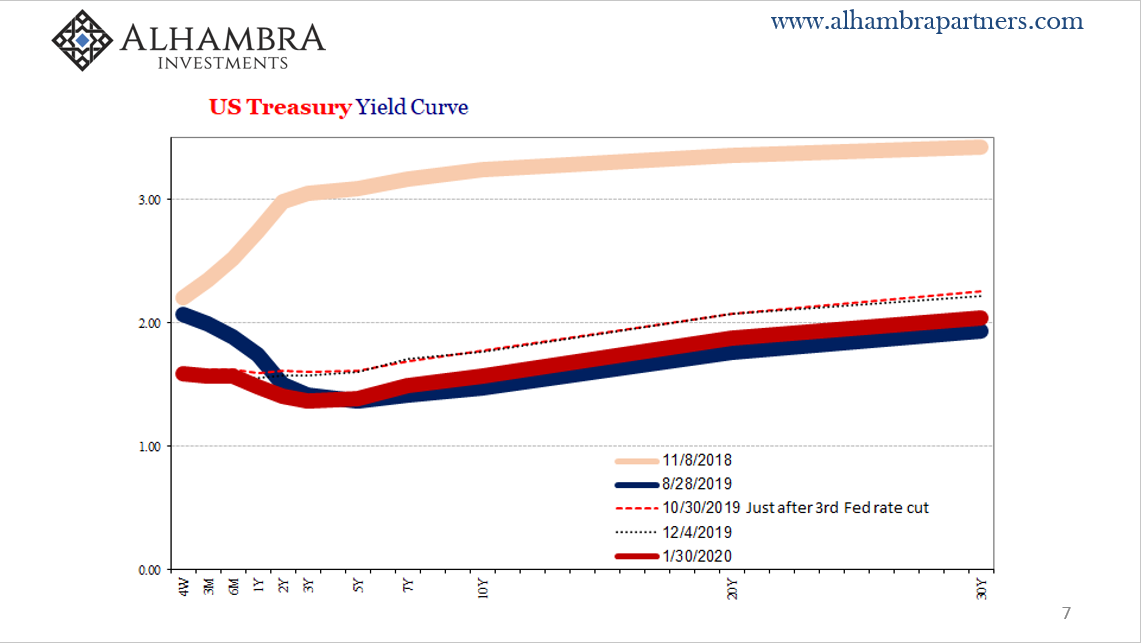

Before getting to those and how they relate to the analogy of microprocessors we’ll first take a minor detour into what the Federal Reserve has been up to of late. You would have thought that what has kept authorities the busiest these past four months was in figuring out what really happened back in September. Not so much.

Four and a half months later, officials still don’t know. This isn’t to say they haven’t provided some guesses; they have. A lot of them. Suspiciously too many.

If you were to pin down Jay Powell and ask him to explain specifically in detail what had occurred and if he answered you honestly, he would have to say he didn’t know. And that’s incredibly odd in a very profound way not the least bit of which is because the Fed’s been very, very busy since October.

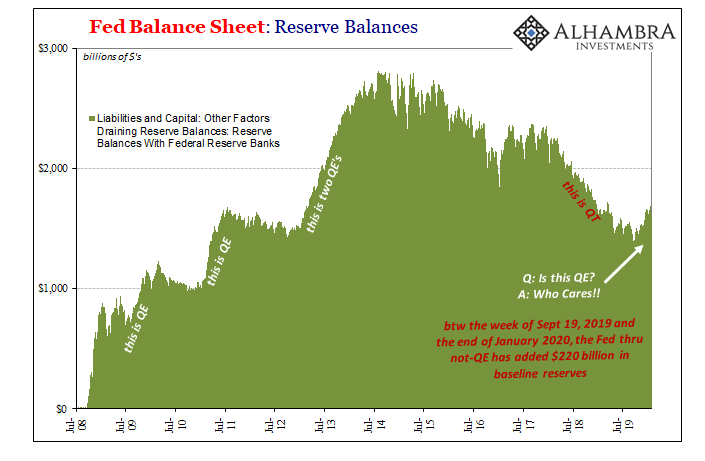

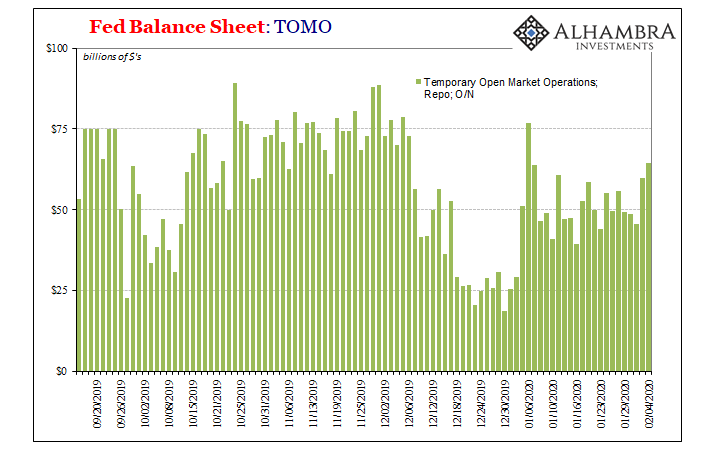

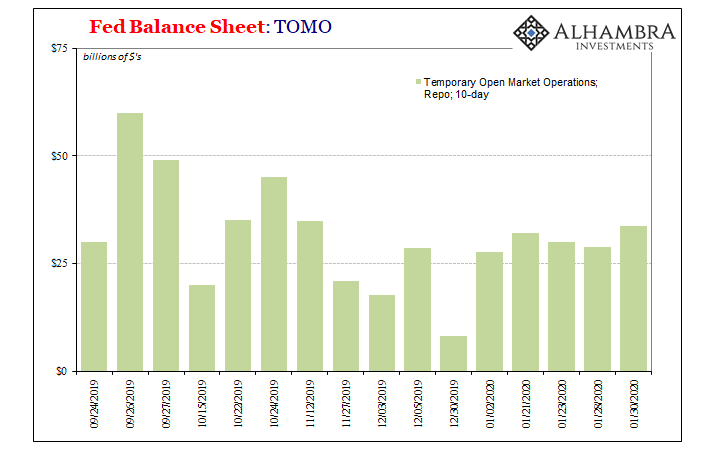

Very busy indeed doing two things intentionally combined. There is not-QE which has raised the baseline level of bank reserves (POMO) by around $220 billion. In front of that program are the repo operations (TOMO) providing marginal source “liquidity” on a short run (mostly overnight) basis.

Jay Powell hoped that it might have been a shortage of bank reserves which, among other factors, contributed to September’s big repo rumble. He couldn’t, however, just create all the bank reserves he came to believe the system needed in one go; can you imagine how bananas the NYSE would’ve gotten had not-QE totaled that $220 billion or more in just October?

Therefore, to be able to slowly, carefully increase reserves the TOMO’s were needed alongside. Once the baseline was raised to a sufficiently high level, what officials these days think qualifies as “ample” or “abundant”, not-QE would be ramped down and the TOMO’s shut down entirely (or mothballed).

But where is that point?

Originally, back in October, it was thought that by the start of 2020 they’d be close to where they needed to be. Now perhaps April. If you don’t know what went wrong in repo, then figuring out the “right” level of bank reserves isn’t going to be easy, is it?

An additional $220 billion in bank reserves and they’ve shown up only in stock prices (and only on psychological effects; there are no monetary links between bank balance sheets and stocks like there had been in the thirties). In repo, there’s still a persisting demand for marginal “liquidity” despite the significantly higher level of reserves.

If this dual-program was working, as the baseline systemic reserve balance went higher the level of activity in TOMO should noticeably decrease. And it did – but only to December. In January, suddenly high demand at the repo “window” all over again.

That’s why Jay Powell now says maybe April.

As I’ve pointed out the whole time, everyone’s attention is focused on the wrong part of this.

The Federal Reserve is raising the level of public reserves which everyone can see (rather the whole point) without any mention of what must be going on with private reserves most people cannot because they don’t know a single thing about them… The visible level of public reserves had been falling but throughout the prior year and a half there were any number of warning signs that the hidden level of private reserves wasn’t picking up the slack as had been expected.

And we continue get the sense this hasn’t changed. Powell keeps hoping to hit the “right” level of public reserves without knowing much or anything about the condition of private reserves – other than they still aren’t keeping everything in line. Therefore, he keeps offering more of the public kind because what else is he going to do?

What governs the supply of private money is simply bank balance sheets, and these have very real internal constraints. None of which is simple, often mathematically-derived properties mostly concerned with the management of risk (if you ever wondered why there are so many derivatives in the world, and how fewer of them can be such a monetary headache, here’s your answer).

In the post-crisis era, however, balance sheets have been fixed for the most part. Like the size of a silicon microchip, there’s a limit. Because the balance sheet can’t (won’t) grow that means the bank has to be more efficient; like transistors, hoping to figure out a way to put more things into the same space.

This is why global banks have increasingly turned, in money dealing, to FX. An FX transaction is booked as a derivative which is massively efficient in terms of balance sheet space. Though that same FX funding arrangement is functionally the same as an offshore repo, from the dealer’s perspective there is no comparing the two.

A repo transaction is booked as a repo transaction, and takes up the balance sheet space required of it even though oftentimes the same dealer bank will have offsetting positions (which, from the dealer’s standpoint, the original repo is for it a reverse repo and the offset being a repo). Therefore, in terms of limited balance sheet capacities the bank can offer a whole lot more of the FX “money” when compared to straight repo for the same committed balance sheet space.

Having noticed the opportunity here, DTCC rolled out something called sponsored repo over the last eighteen months or so. Through its aptly named FICC subsidiary, the custodian “sponsors” dealers who, they tell the public, combine their efforts in a central clearing manner to make the whole thing safer.

In truth, the entire point is to increase balance sheet efficiency for participating dealers; to make straight repo more like FX. Briefly, the way it’s done is by putting the third party custodian in between counterparties on both the cash and collateral sides. This has the effect, in balance sheet accounting, of allowing the dealer to net out reverse repos with repos, dramatically reducing the overall balance sheet space required for all of them.

Sponsored repo, as you might expect, is becoming very popular. So much so that some have sought to blame it (as well as too many other things) for what went on in September (I won’t get into those particulars here). In response, one DTCC spokesman said, and I’m paraphrasing, AYFKM! You can see their point, as I wrote.

Sponsored repo wasn’t trying to fix a problem in repo, it was invented as one possible way to do repo better under this questionable monetary environment of balance sheet, not bank reserve, scarcity. In a strange but very real way, DTCC was actually doing the Fed’s job! To get more (usable) money into the system by trying to squeeze blood (funding) from a stone (balance sheet capacity).

After all, think about what sponsored repo is accomplishing – essentially what the Fed is supposed to only in the place where it matters. By being more balance sheet efficient, dealers can expand these hidden capacities for hidden private reserves using up the same or less precious balance sheet space. The more sponsored repo takes place, the greater the “money supply” should be.

It’s not quite Moore’s Law but it is more like monetary expansion than QE, not-QE, and all the TOMO’s. That’s what the DTCC spokesman alluded to, that sponsored repo can only be helping not hurting.

If there is a question about it, it’s how much it has been helping. Is it enough?

Probably not. Here we are still having problems with repo such that Jay Powell after $220 billion can’t figure out what level of public reserves qualifies as abundant.

When I say the economic turnaround better turn the economy around and soon, I mean that for more than just real economy conditions and factors. That’s a bit about financial and monetary risk, too (what a possible rollover of commercial credit in both the US and Europe might indicate on that front). The greater the perceived risk, the scarcer balance sheet capacity becomes. Private reserves.

Gordon Moore thankfully never had to deal with a situation where the size of the silicon chip actually got smaller. If he had, it wouldn’t have mattered how efficient Intel or one of its competitors could be in fitting individual transistors on one. If you have less overall space, unless you can make a giant leap in efficiency computing power is going to suffer.

Sponsored repo was and is a leap of efficiency, but it’s still ramping up and can’t be expected to accomplish big things. Thus, if balance sheets are being scaled back at the margins (again), this trend toward monetary efficiency might easily be overwhelmed. No matter how far Jay Powell takes his quixotic quest.

Stay In Touch