The rules of interpretation that apply to the payroll reports also apply to other data series like retail sales. The monthly changes tend to be noisy. Even during the best of times there might be a month way off trend. On the other end, during the worst of times there will be the stray good month. What matters is the balance continuing in each direction – more of the good vs. more of the bad.

Or when what seems to be a good month is less good than it used to be.

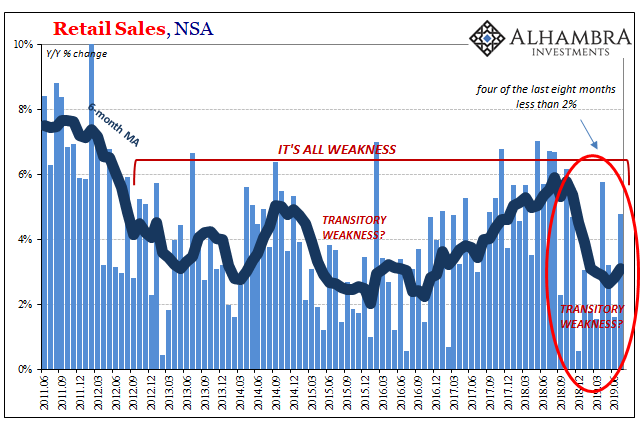

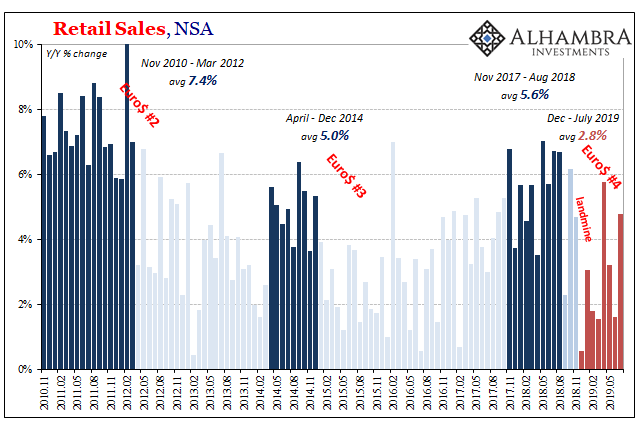

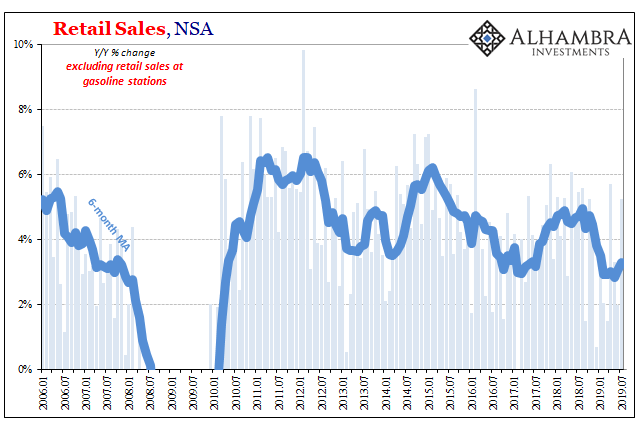

Retail sales had managed nearly 6% year-over-year (unadjusted) growth back in the month of April 2019. It came during the mini-outbreak of green shoot hysteria; the idea that either the economic soft patch would be transitory or the Fed pause would keep it that way.

Ironically, it was CNBC (of all places) which a published the most balanced and reasonable take on retail sales (referring to the seasonally adjusted series):

Retail sales have been on a seesaw pattern, rising at a healthy pace in January, then falling in February, followed by the big jump in March and now a drop in April. The data suggests Americans are reluctant to spend freely, despite steady job gains and modest wage increases.

Over the next few months, the picture would remain the same – a few really bad months, one of which contrarily seemed really good in seasonally adjusted terms, and now July’s estimate. At 4.79% year-over-year, the latest is by no means fantastic but given the downward revised estimate for June (just 1.60%), near 5% might otherwise appear exceptional.

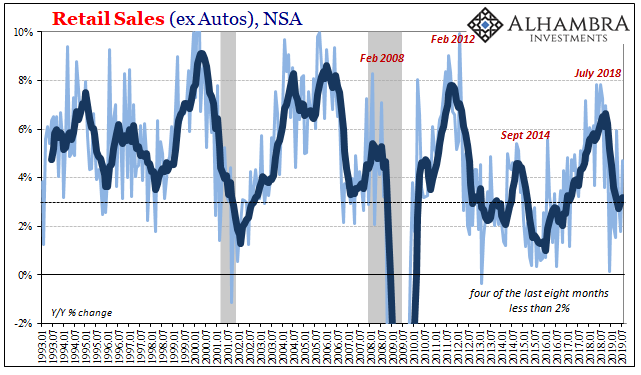

A single monthly figure is simply meaningless. Instead, over the last eight months (since the landmine) there have been four months with increases less than 2% and only twice has the gain been more than 4%. On balance, consumer spending has clearly turned downward despite all the continued (emotional) attachment to the unemployment rate.

Even July’s seemingly good month would have qualified as a questionable one a year ago.

There is some distortion in the current monthly figure, too. Amazon Prime Day, which was held starting July 15, was by all accounts a huge success for Amazon. The company said it sold 175 million items during the expanded 48-hour sales window. That’s up from 100 million the year before. While those figures relate to every country in which the event applied, eighteen of them this year, there’s every reason to believe that there was a very real effect on US sales.

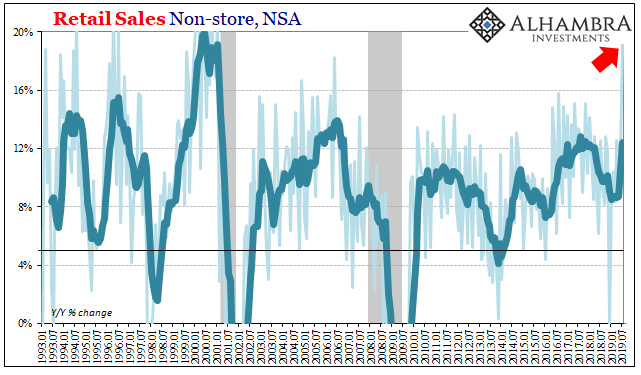

Amazon did not and does not disclose specific gross merchandise values or volumes, but we don’t really need their estimates. Prime Day very clearly shows up in the Census Bureau’s figures for July.

Sales of non-store retailers rose by nearly 20% year-over-year last month. That’s the best month for this category since the dot-com era. This would propose that Prime Day wasn’t just a success, it was enormously fruitful.

There are two ways to take this result, though. On the one hand, good for Amazon being able to pull off a huge retailing feat. In the dog days of summer, no less. It could suggest American consumers are hungry.

Or, on the other hand, it might indicate Americans have become so cautious they’ll only jump on what (they believe) are really good deals. In the post-crisis era, non-store retail sales counterintuitively generally pick up when the economy (meaning labor market) has been on the downswing.

The averages all suggest that direction. If so, that would mean any “excess” Amazon was able to grab in July will have been pulled forward from August (the height of back-to-school) and perhaps September, too.

The problem is the labor market – in both analysis and for these economic descriptions. Even in CNBC’s earlier commentary quoted above they repeat the same standard language; “despite steady job gains and modest wage increases.” The labor market is, in everyone’s mainstream estimation, still strong. Therefore, weak or uneven retail sales don’t make much sense.

It’s therefore much easier to dismiss this condition as “transitory.”

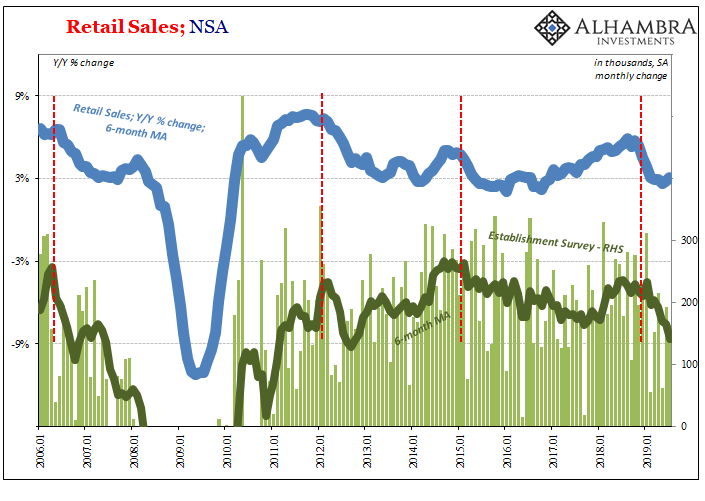

The correlation isn’t perfect, considering there’s price changes in retail sales data, but the whole “steady jobs gains” idea just isn’t true as you can see above. There’s been a very clear shift in the US labor market – one that hasn’t been captured by the unemployment rate, nor is there a determined effort to appreciate it given the spectacle of every payroll Friday to claim blowout numbers in whichever single month (even though those, too, have become much less frequent and smaller).

If consumer spending has slowed, and it has, then it’s because at the margins Americans can sense the economy and the labor market did. The Euro$ landmine shows up in both the employment figures as well as retail sales. The unemployment remains the wrong way to assess the situation.

What happens from here on is a matter of how the rest of the economy continues to react to “overseas turmoil” and the growing recession in the goods economy. If the labor market maintains the same trajectory, even if it doesn’t unleash a huge wave of immediate layoffs, we should expect more of the bad retail sales months and only a few good ones like July that aren’t really all that good.

Stay In Touch