Economic relativity. One datapoint or economic circumstance may be said to be good, maybe great, in relation to another, but if the second isn’t really all that good maybe the first is just better than bad. Terms like “strong” and especially “recovery” should have more rigid definitions and be judged by more complete standards.

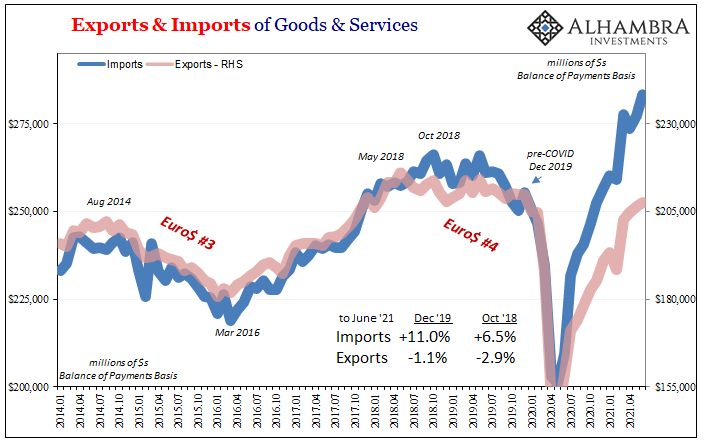

If you are looking for a snapshot as to why there is so much to this “growth scare” and rising deflationary potential (record stocks, though), outside recent labor market data you’d be hard pressed to do better than US trade statistics. It’s worth an update if only to see how little the situation has changed:

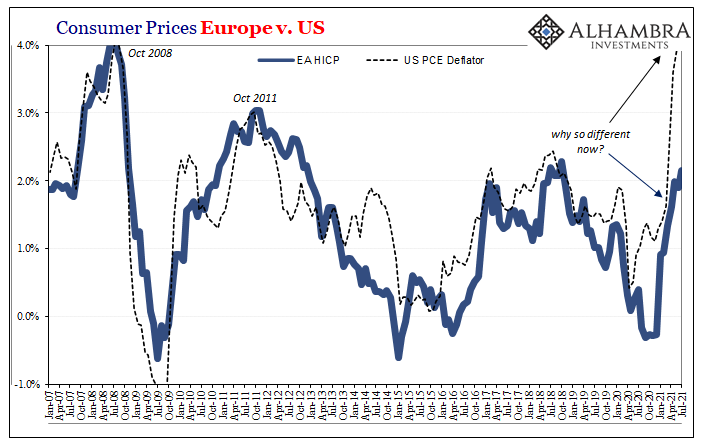

In this we can see already the discrepancy between US inflation and calculated consumer price changes throughout the rest of the world. American demand for foreign goods compared to foreign demand for American goods is not comparison at this stage – even though, strong inflationary global recovery narrative, these two data series should be converging closer together especially as reopening gets completed in more places.

If US trade stats are reasonable approximations of the general state in each place, and I think they are, the artificiality of the US side is made plain and obvious for what is a clear divergence for the era of Uncle Sam’s helicopter drops. Short run bursts in them, consumer prices – for now – have been boosted, too.

But is US demand good? Or great? It may seem so when compared to the amount of exports going out. This, however, is no true standard for comparison, as the export series already lacks context of its own which otherwise shows just how atrocious the state of the rest of the global system must be for such continuously diminished outbound trade.

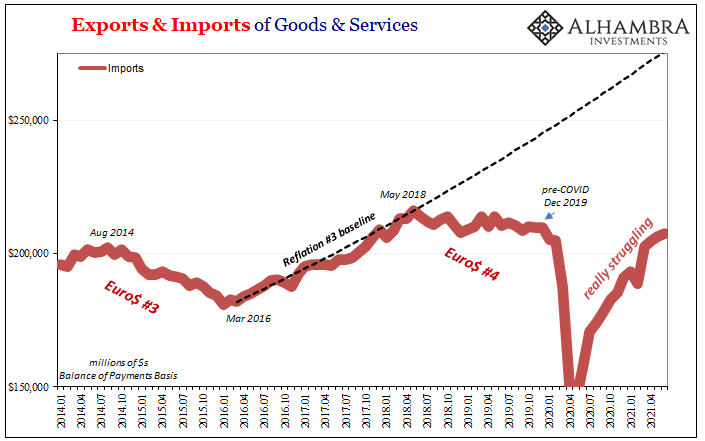

It’s not just in comparison to last year, but more so in terms of squandered time. The trade recession, so to speak, actually began way, way back in May 2018 (and it was never “trade wars”). Not only are exports in June 2021 (latest update) less than February 2020, they are much less than that May three years ago (only fractionally better than August 2014!)

Not only hasn’t the global economy caught up from the 2020 recession, is hasn’t yet even worked into the prior one even halfway through 2021.

But if US exports – our proxy for the rest of the global economy – are so evidently off, the very opposite of strong in every sense and dimension of their economic condition, where does that leave imports as proxy for US demand? Better than exports cannot, therefore, tell us all that much.

There’s no question the flow of imported goods is increasing, quickly in some multi-month periods, still that doesn’t by itself add up to an inflationary tell-all. On the contrary:

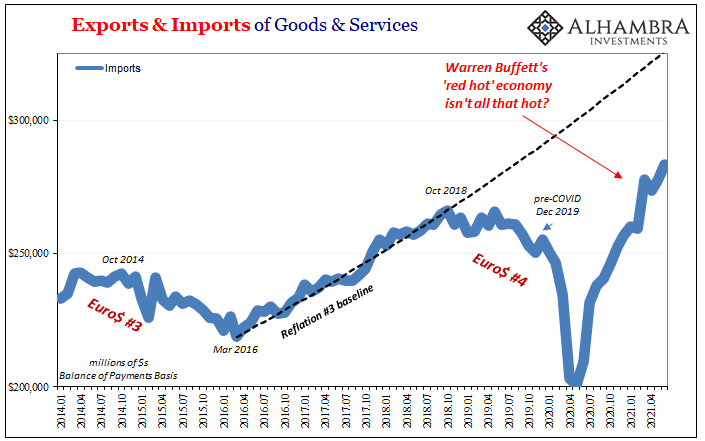

While on this side it may seem that the American economy, boosted massively by federal government transfers, has fully recovered from 2020 and then some, even suggesting going too far into the inflationary excesses, it actually has not. Imports, like exports, have yet to recover from the whole recession.

Why not?

Better than last year, and better than exports, these are not by themselves meaningful measurements.

When the best of the best of the best segment of the global economy, with everything imaginable going in its favor (save one), and it still doesn’t quite add up, yeah, growth scare. What does this everything look like when all that artificiality really does fade?

Rather than exports rapidly converging with imports, maybe imports begin to converge back toward exports; neither having come close to recovery beforehand.

Such globally deflationary probabilities made more probable as eurodollar woes might continue to pile up. The one thing global trade doesn’t have on its side, the one thing it will need if ever to become realistically strong.

Stay In Touch