In Japan, they call it “powerful monetary easing.” In practice, it is anything but. QQE with all its added letters is so authoritative that it is knocked sideways by the smallest of economic and financial breezes. If it truly worked the way it was supposed to, the Bank of Japan or any central bank would only need it for the shortest of timeframes.

That would be powerful stuff.

Instead, in June last year the narrative shifted (again). Surpassing half a decade of this “easing”, it became clear after an upward start to the year inflation wasn’t going to come anywhere close to meeting the official price mandate. This time the central bank would try and blame online shopping for its apparent defeat. Seriously.

Fast forward eight more months and BoJ now signals it stands ready to do more. Reversing itself entirely, where once Kuroda’s gang openly talked about ending the thing, a year later they are back to taking it up a notch; this “easing.” Japan’s central bank is joining the rest of them in turning “dovish.”

If (yen strength) are having an impact on the economy and prices, and if we consider it necessary to achieve our price target, we’ll consider easing policy.

Governor Kuroda can blame the yen just as he blamed Amazon, that doesn’t change the situation for “powerful monetary easing.” Again, if it actually was what Economists say it is, then the yen would be following BoJ’s policy direction as it had in the earlier days of QE and QQE.

Something changed.

It’s very easy to see what. The global economy ended 2017 on somewhat of a high note; very high, according to central bankers. It finished up 2018 moving perhaps quickly the other way. The question now isn’t the direction, it is how far against expectations this downturn might progress.

Kuroda’s new “easing”, the Fed pause, and the ECB’s aborted liftoff together suggest globally conditions are already fraught with clear difficulties. Central bankers are always the last to figure these things out. If they are turning on policies, economic inflection is past tense.

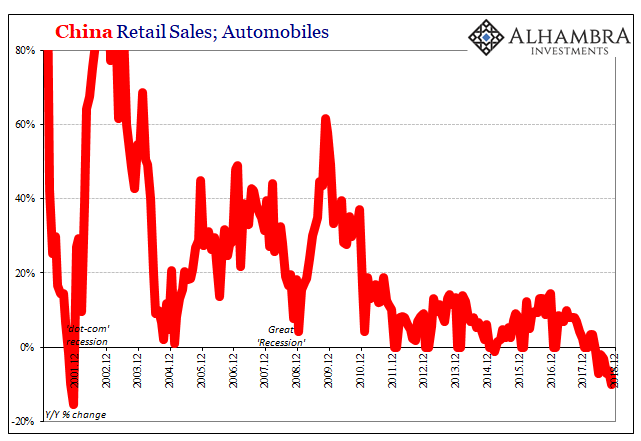

Out in front leading the way are the unfortunate Chinese. Germany may stake a claim to certain high degrees of negativity, but in the manner of unusually bad indications right now China is winning (meaning losing). In yet another ominous sign, auto sales tanked again in January.

Down more than 17% year-over-year last month, unit sales are plunging in a way unfamiliar to modern China. This is pre-market reform stuff, the kind of setback that suggests something very unusual is going on.

China’s NBS won’t update any of the big three statistics (Industrial Production, Retail Sales, Fixed Asset Investment) for January in keeping with its normal annual pattern. The Golden Week either in January or February each year is too much of a skew which complicates the monthly data. Rather than attempting a seasonal adjustment, the government just puts the two months together. Therefore, we won’t know just how bad retail sales of autos might have been in January (plus February) until the middle of next month.

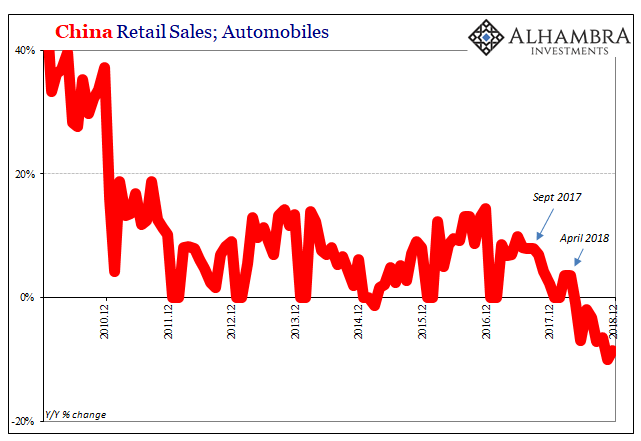

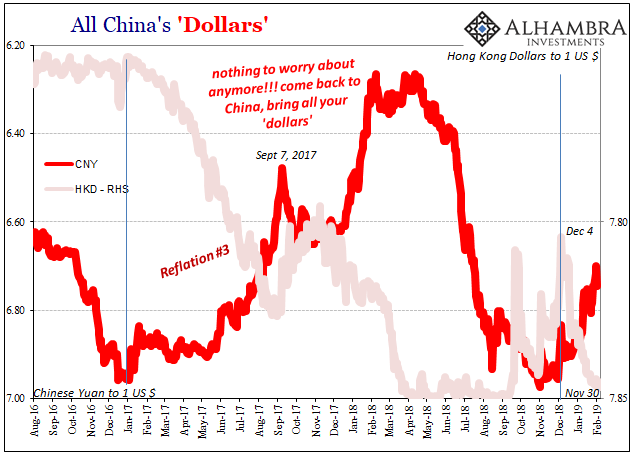

It’s not just the first sustained reverse in modern times that grabs our attention, it is as much if not more when that reverse began. It picked up starting in October 2017 coincident to both the 19th Communist Party Congress (the one that said prepare for a China living in a no-growth world) and some serious eurodollar-based volatility. CNY was rapidly accelerating upward until early September that year.

Then starting in May 2018, Chinese car sales tanked. This takes on the proportions of CNY’s concurrent track. Following the currency’s plunge in June, itself following the clear eurodollar break on May 29, retail trade in autos sank 7% in that same month. The biggest auto market in the world hasn’t recovered any momentum since.

According to the latest data from outside sources, it didn’t recover any momentum in January 2019, either. It got worse.

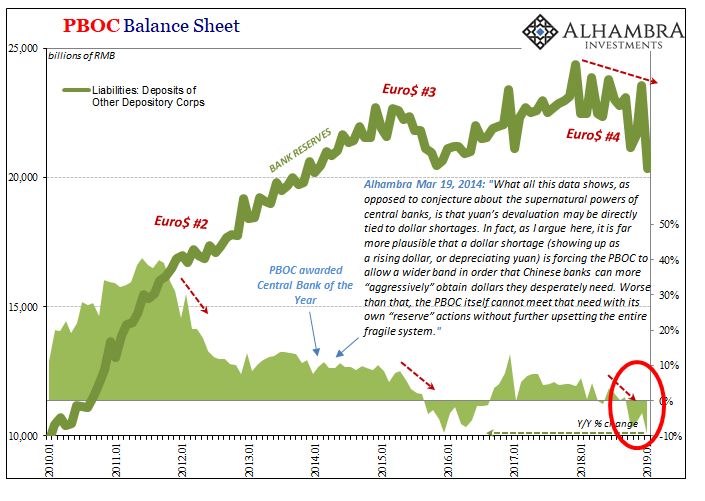

What is different about 2018-19? The monetary squeeze. At least during Euro$ #3 China still had some margin or economic elevation to absorb that event’s money drain. Reflation #3 was far too small and brief to provide the same capacity for what is surely now Euro$ #4. Money contraction hitting during a semi-weak state is bad; the same starting from a very weakened state leads to the historically unusual.

And, as one market analyst admitted in light of Monday’s auto numbers:

…downward pressure is still there. The government isn’t adopting stimulating policies to give the market a shot in the arm.

Stay In Touch