Headline employment continues to look tepid, but at least moving in the right direction. However, that does not square with the GDP report from earlier this week. The headline Establishment survey average of the past few months appears inconsistent with such GDP weakness. Economists have been quick to point to the BLS employment numbers as confirmation that GDP is not as bad as it appears, and thus the impulse to remove inventory and government spending from GDP is the correct analysis (the “best looking contraction ever seen”, some government official noted).

Fixating on the numerical count of employed Americans misses the critical issue when analyzing not only the economy but the failure of monetary policy to address weakness more directly. Having a job is not the same as having a good paying job. Income to the personal sector through labor has been the primary malfunction of the recovery from the Great Recession.

Under the numerical counting of employed vs. unemployed, the Household survey (which was far weaker in January than the Establishment survey) shows 1.714 million additional employed persons in January 2013 over January 2012. Over the same period, the civilian labor force grew by 1.298 million persons, but overall noninstitutional population (potential labor force) increased by 2.394 million. Over 1 million potential laborers are unaccounted in the employment statistics, showing up as those “not in labor force”. That is the crux of the participation problem.

We know from the jobless claims data that the number of persons rolling off Unemployment Insurance is close to 2 million. That means along with the 680,000 new potential workers that did not find a job and not counted in the labor force, there were 2 million previous workers that now have no means of income (institutional or earned). Job growth, even in this bean counting sense, is not enough to keep pace with the expansion of the population and the re-absorption of those displaced during the Great Recession. All these people have to feed, clothe and shelter themselves and their families (is SNAP enough? Perhaps for survival, but far short for actual economic expansion).

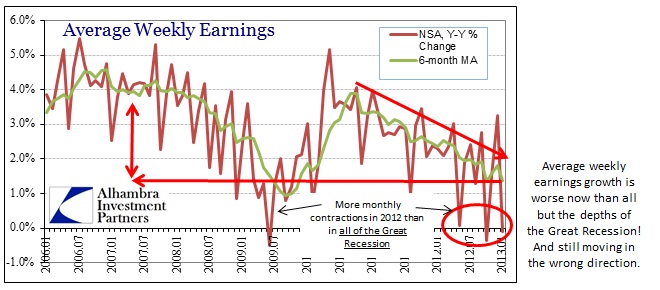

Aside from this fixation with numerical assessments, the far larger problem is the quality of jobs being created. Income and pay growth are moving in the wrong direction. Not only is wage income growth decelerating, it is doing so at levels not seen since the worst days of 2009.

This is a conclusive indication that wage growth is not sufficient to replace lost income from the housing bubble period. Jobs that are being added in this “recovery” are inferior to those lost in the collapse. Economists are puzzling over this defiance of Okun’s Law, but it really is not much of a mystery.

That presents two simultaneous economic complications. In the strict, bean counting sense job growth remains far too tepid to absorb both new workers and the previously displaced. And those that are lucky enough to find employment are doing so with income levels that are not growing near fast enough (in the aggregate) to keep up with any real meaningful sense of cost of living pressures (ignoring hedonics).

This far more complete sense of employment is more consistent with Q4 GDP as presented (even setting gov’t spending aside) than a “robust” employment picture that reassures economists Q4 GDP was an aberration. Jobs, by themselves, do not matter. Income does.

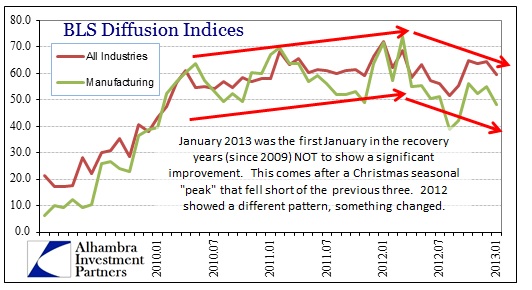

Looking forward, there are ample warning signs about even nominal job growth. Diffusion indices for private employment, especially manufacturing, are not signaling a near-term ignition of recovery spirit and activity. Instead, this piece of data actually portends weakening (initially as volatility) in even the bean counting.

Reconciling weak GDP and employment is not exceedingly difficult when it encompasses more than just numerical fascination. Economic progress is far more about quality than quantity. Not only does that mean economic weakness (even contraction) can occur coincident to increased employment headcounts, it also means that monetary policy is targeting the wrong variable.

Stay In Touch