In addition to indications for a gathering slowdown in export power Germany, the UK has followed a similar line of late. That would make sense since both Britain and Germany are essentially the same kind of economy separated slightly in geography and currency. They both make much of their growth from the same marginal space; financial services, exports to the rest of Europe and exports to the outside. The crush of the real estate boom perhaps reversing along with, relatedly, financial uncertainty worldwide, has left the UK in a more precarious state now after the Bank of England having already taken credit for engineering a full recovery path.

“The UK economy’s momentum has begun to ease in light of increasing uncertainty and a weaker global environment, as we expected, but remains decent,” Barclays economists said in a note to clients.

Growth was almost entirely driven by Britain’s dominant services sector, which picked up pace from the second quarter, while manufacturing shrank for a third quarter in a row and construction suffered its biggest contraction in three years.

Year-over-year, UK GDP slowed to 2.3% which was the lowest expansion rate since the middle of 2013; though, it has to be pointed out repeatedly, that is much, much better than most other advanced nations. But, we are told in rather charitable connotations, even with the slowdown the UK is apparently in a much better place:

Britain’s economy as a whole is now more than 6 percent larger than before the financial crisis, but neither the manufacturing nor the construction sectors have returned to pre-crisis levels of activity.

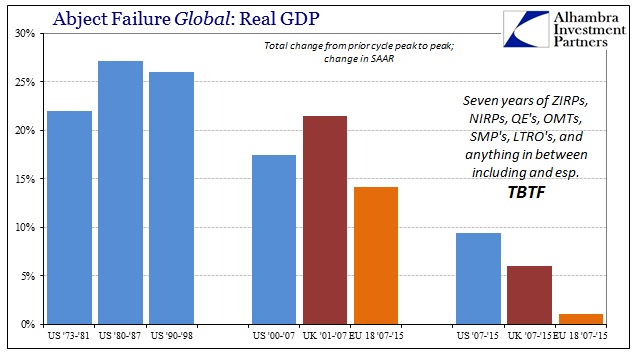

The open mimicking of Bernanke’s benchmark of success is dispiriting, as 6% total growth over almost eight years is, as noted of the US economy today, an abomination. It is little wonder that such a diminished standard would be shared with Britain since both contrast, as the former Fed Chair asserts, with European monetarism. In other words, the Bank of England enthusiastically embraced QE’s just as much as the Federal Reserve (in purported contrast to the ECB’s “conservative” German elements).

Yet, that comparison actually leaves the UK as cold and remote as the US. From the 2001 peak to the 2007 peak, a comparable length of time, British real GDP had done far better just like in America (and both were still letdowns from cycles before them); measuring more than three times the total growth at 21.5%. So again, Bernanke’s attempt at reductionism falls starkly flat into uniform reality. Worse, for his rehabilitation, the EU economy similarly underperformed in the last cycle; EU 18 real GDP only gained 14.1% peak to peak. In short, the fact that the US (and UK) outperformed Europe in this cycle may not have anything to do with US (or UK) QE’s and monetarism at all.

Instead, that circles our analysis right back and squarely upon QE itself, as practiced at either end of the Atlantic Ocean. No matter what any central bank has done in any location, growth (as measured by GDP) has fallen apart. That view is preserved in each geographical distinction regardless of the type of monetarism practiced within them, again suggesting that none of it actually worked (s) and that instead the unifying, terrifying economic factor is much more than any central bank’s ongoing dubiousness.

Bernanke failed, as the BoE and ECB, not for lack of trying or even in the method of that insanity but rather because none of them stood a chance. Had they made that realization about the “dollar” they might have figured out (though not likely given the strident conviction of their ideological bias) that their interference only made a bad situation that much worse. The last thing the global economy needed was more and shakier financial bubbles placed upon the rotting economic foundation of an involuntary de-financialization.

Had these same central banks instead embraced the opportunity to further that cause, and to undo the prior imbalances and financialized damage to the global economy, it may have been worse but only for a short time; and by now, with so many years gone by already, the global economy much, much better for taking the challenge. Instead, orthodox monetarism only goes back to the same failed process time and again; shrilly trying to turn that disaster as if it were the measure of success.

Former BoE chief Mervyn King, himself no stranger to the siren song of QE, only found that reckoning long after he plastered the UK and sterling with Bernanke-approved monetary disintermediation.

In his first public speech in England since his term at the BoE ended in June 2013, Mr King said he was concerned about a persistent weakness in global economic demand, six years on from the depths of the financial crisis.

“We should worry about that,” Mr King told an audience at the London School of Economics, where he was once a professor.

“We have had the biggest monetary stimulus that the world must have ever seen, and we still have not solved the problem of weak demand. The idea that monetary stimulus after six years … is the answer doesn’t seem (right) to me,” he added.

Unlike King, the mainstream economic status quo seems intent to reduce the standards by which monetarism is to be judged. It is the only way their orthodoxy can stand; such misleading and obtuse positioning depends upon the rest of the world not noticing the ongoing cost and destruction. There hasn’t been any difference in economic performance between the US, UK and Europe; all are disastrously deficient and for the same reason. The ongoing cost in terms of lost time is already enormous and we cannot truly afford these economists getting away with running up the bill still further by refusing to face up to evident reality.

Stay In Touch