The Chinese have been reforming their monetary and credit system for decades. Liberalization has been an overriding goal, seen as necessary to accompany the processes which would keep the country’s economic “miracle” on track. Or get it back on track, as the case may be.

Authorities had traditionally controlled interest rates through various limits and levers. It wasn’t until October 2004, for example, that the upper limit on lending rates was rescinded. In August 2006, the mortgage rate floor was set for the first time at 85% of the government’s benchmark. In July 2013, the lower limit for the lending rate was removed entirely.

While liberalization in finance had been slow, the dribs and drabs of glacial, grudging change, the pace suddenly quickened in early 2015. It was as if Chinese officials had been rushed to meet some unknown and hastily imposed deadline.

The Peoples Bank of China had always been reluctant to let banks decide deposit funding for themselves. A relic of old Communist thinking, there had remained anxieties and opposition about what could happen when banks “compete” for deposits. Authorities feared an out-of-control bidding war and therefore an out-of-control interest rate and monetary environment.

China’s deposit rate infrastructure was perhaps the last mile on the long road to market reform. In March 2015, the ceiling was abruptly changed, moved to 130% of the benchmark. Two months later, 150%. In late August, the PBOC announced that the interest on term deposits of longer than one-year maturity would be uncapped. Finally in October 2015, the ceiling was scrapped for all deposits.

When the central bank let the long-term deposit rate float, it said, “This marks another important step forward in interest rate marketization reforms for our country.” The timing, August 2015, was shall we say curious. You might remember that particular month for other reasons.

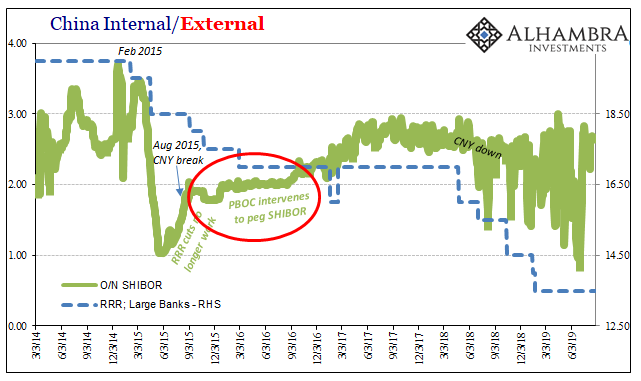

Not only had CNY been shall we say monkeyed with, ultimately producing far less-than-desirable results, there was another oddity becoming very visible in RMB markets. The overnight SHIBOR rate had been rising (though benchmark rates were being cut) and then near the end of August – the very day of the deposit rate announcement – it just stopped.

For the next year, it would trade in a very narrow range (never above 2.05%).

There are no official letters and memos about either CNY or SHIBOR. Therefore, any interpretations we make are speculative. As always, you are free to interpret these signals and draw your own conclusions.

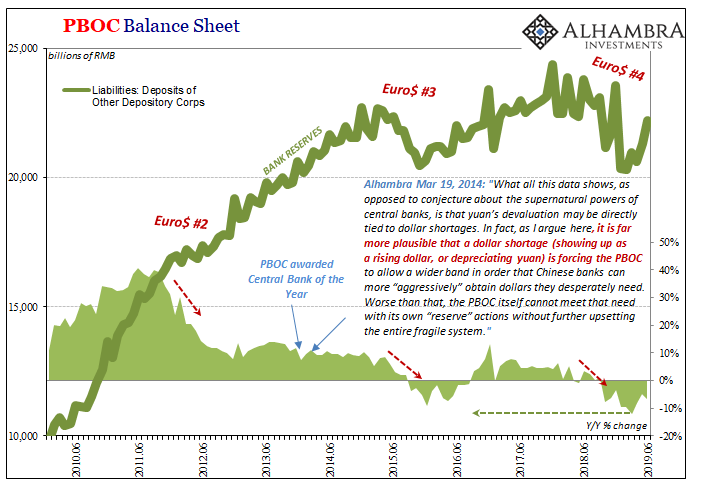

Here’s what I think happened. Confronted with a range of very bad choices in late 2014 and early 2015, the PBOC found itself more and more involved across a broad and deteriorating monetary front. There was an unofficial peg on CNY (for a time) and then another on the main overdraft rate (SHIBOR). That’s a lot of ammunition critics might use to level charges of manipulation.

To head off those potentially damaging assertions, authorities sped up the tide of liberalization in other areas which were not so crucial so as to cover themselves against what they were doing where it was. Pay no attention to SHIBOR, can’t you see we’ve given in and completely changed the way deposits work!

The liquidity problems in 2015 had nothing to do with deposits and deposit rates, easy enough to move up whatever timeline had been in the works. SHIBOR and CNY, however, these were at the center. Reform was a real distraction, both to take focus off intervention as well as remove it from the things behaving far from ideally.

Like pegging CNY for those few months March to August 2015, pegging the overnight SHIBOR rate was far from idyllic – and for all the reasons critics charge. Clandestine manipulation is the last option for scoundrels. You only do it when you have no other choice.

I bring all this up for two reasons, both of which I can’t help but wonder if they are related. The first wasn’t announced until this weekend. The Chinese are (surprise!) liberalizing their finance system and interest rate mechanisms again. Having done very little between, say, 2016 and 2018, in 2019 there’s suddenly renewed interest in “market reform.”

As usual, the mainstream media sees it as a quasi-stimulus maneuver. Is there anything the PBOC does that the Western media won’t characterize as stimulus? I swear, there was an episode in early 2016 when former Governor Zhou Xiaochuan sneezed at a press conference and someone in the financial press wrote about its positive effects on credit (though I am being equally guilty of sensationalizing it here in recalling the story).

The details of the policy change are almost irrelevant. Most of these benchmarks, ceilings, and floors are set by China’s government. The central bank is just one agency among many in the Communist apparatus aspiring for “optimal” economic outcomes (the very thing the Western financial media admires most: the spirit and idea of technocracy).

The new plan involves changing the way Loan Prime Rates (LPR) are calculated – and potentially how they are used. LPR’s are the interest quotes banks give their best customers. Now, eighteen banks are going to submit their LPR’s to the PBOC on a monthly basis and the central bank is going to publish an average or weighted average of them.

According to China’s central bank earlier today, this will “deepen liberalisation of interest rates, improve interest rate transmission mechanism, and help to cut financing costs in economic activities.” It has been widely hailed as a stealth rate cut.

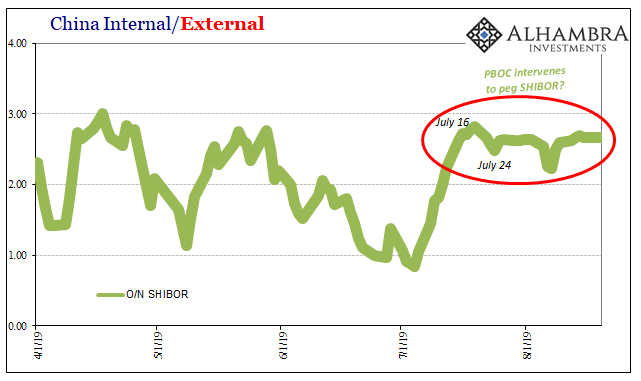

It may better be characterized as another distraction; a peculiarly timed one. The second thing about all this, not only is CNY being defined by a series of ticking clocks at the moment, take a look at SHIBOR recently:

Apart from two days earlier this month (that little V-shape in early August), the overnight rate has uncharacteristically moved very, very little day-to-day. It started in the middle of July, and since late last month there’s really no other explanation. A “market” spending an entire month in a narrow range reeks of manipulation (in mechanical terms, consulting with banks and setting OMO’s to match overdraft demand without limits).

And just as this weird peg-like behavior in the key liquidity rate breaks out, all of a sudden the PBOC is keen to announce another form of market liberalization (which also gets labeled as a right cut on top); reform that overall has very little to do with anything relevant in question. All convenient coincidence, I suppose.

Again, there is no confirmation nor will there ever be. In my own opinion and analysis, I see China’s central bank getting backed further into a corner and having been left few appealing options it is just rerunning the playbook it used last time – even though it didn’t work out so well four years ago. For that reason alone you have to wonder just how few choices the PBOC has available.

To me, a pegged overnight SHIBOR rate represents another serious escalation in the eurodollar/RMB nexus, the great monetary squeeze beyond the influence of any central bank. Not much good followed August 2015. China seems to be replaying a lot of August 2015 right down to its distracting trivia.

In the oddest twist of all, the more the Chinese want you to think reform the more they are having a hard time with markets.

Stay In Touch