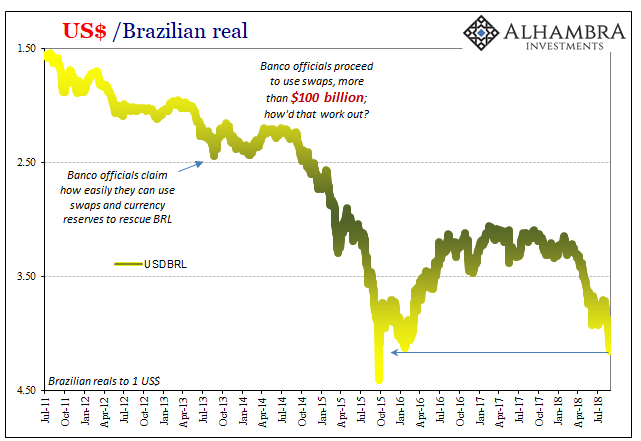

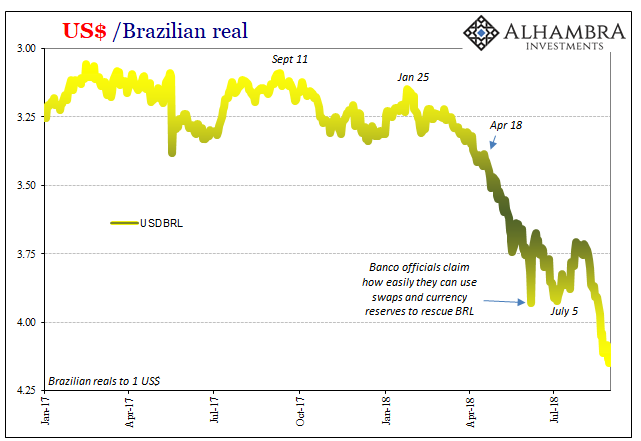

It’s hard to believe it was only about three months ago. Time flies when disaster unfolds all around you. In early June, Brazil’s central bank arranged a press conference where its President Ilan Goldfajn would set everyone straight. The currency was falling, he admitted, but it would be easily handled by closely following the Portuguese version of the global central bank handbook.

Sometimes you just have to admire the unrivalled brazenness of these guys and gals. Or, as I put it at the time, Goldfajn just called everyone stupid. He would have to believe that of us because Brazil has been through this before. Not in some long distant past disgrace, but just a few years ago. In fact, as he spoke, Brazil still hadn’t yet begun its recovery from the last time.

I couldn’t resist what I still think was appropriate snark in response:

We are just short of five years from when the last Banco chief called a press conference in 2013 to declare pretty much the same exact thing. Only then, Banco acted and had initiated a swap program that by early 2015 had extended to more than $115 billion. It ran so smoothly, the Brazilian economy is today celebrated as the model for how all EM crises should be handled.

Just kidding. Of course not. The real crashed and with it the Brazilian economy.

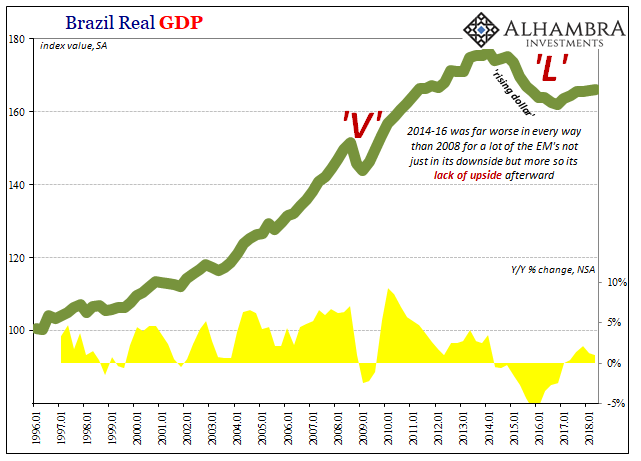

Is that ahead for Brazil, repeating the nightmare? Today’s statistics for Q2 2018 aren’t looking good, not that anyone who isn’t stupid would have expected otherwise.

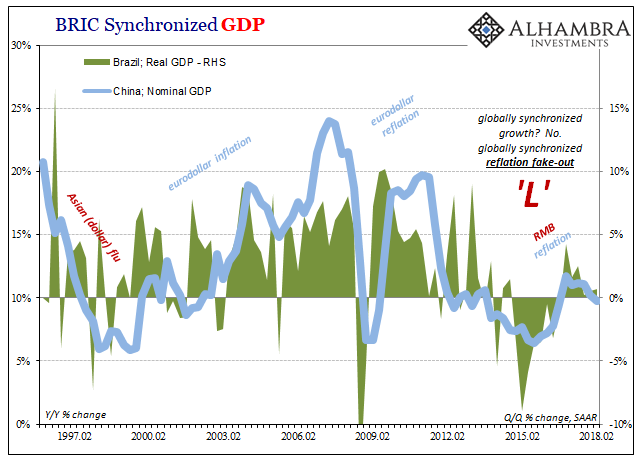

Brazil’s economy had been decelerating for some time before. The currency, meaning dollar, and economy go hand in hand in that regard. Both BRL as well as Brazil’s economy each fell into an obvious “L” pattern. That’s not a very good template to follow in either direction, but it makes the potential re-emerging downslope that much more precarious.

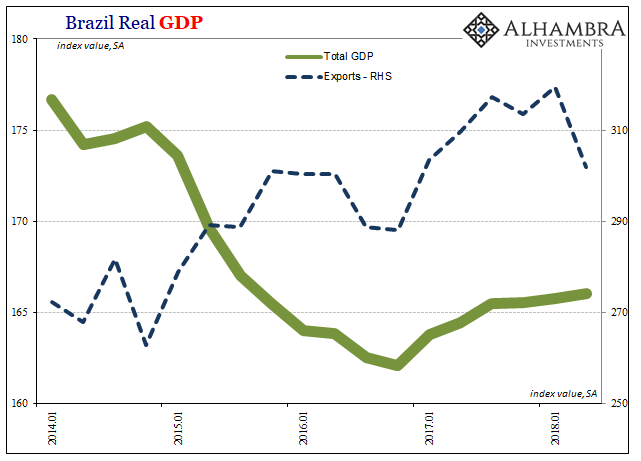

Since the middle of last year when renewed “dollar” troubles arose (Q3), Brazilian GDP has been slowing. In the latest quarter, Q2 2018, real GDP grew by just 1% year-over-year. Not only is that the weakest in over a year, it’s becoming obvious in which direction everything is heading.

At its best point, real GDP expanded by a little more than 2%, the disappointing fruits of 2017’s globally synchronized growth. Following several years of the worst sustained contraction (inarguable depression) in the country’s history, to only “recover” that little suggests more than recent issues holding back not just Brazil’s economy.

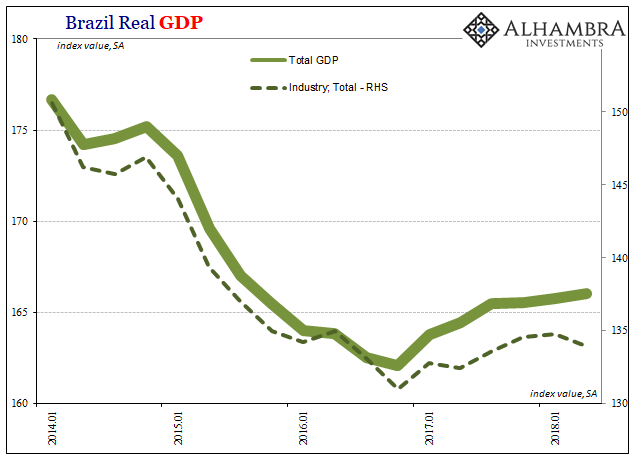

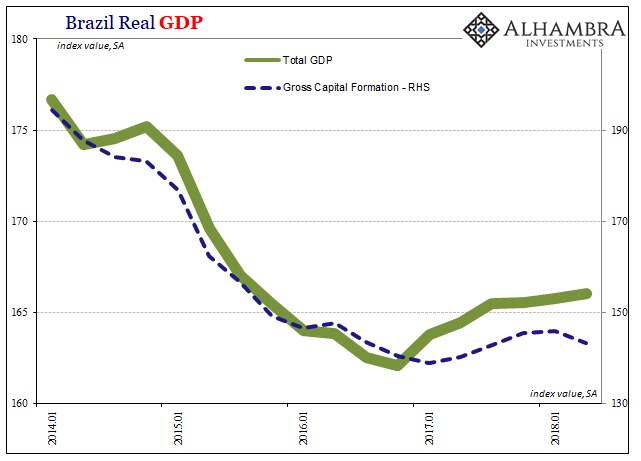

If last year disappointed, this year was supposed to make up for it. That’s no longer likely to happen (it wasn’t a good bet to begin with). While GDP remained positive, the key internals did not. Both industrial output and gross capital formation fell in Q2 reversing again only small gains during the last “reflation.” Industry declined by an annual rate of 2.4% (Q/Q, seasonally-adjusted) while capital formation fell by a sharp 7.2%.

The relative overperformance of overall GDP expansion, if it can be called that, during 2017 was due to the usual export contributions. As a resource economy, at the margins the export sector is a big contributor. In Q2 2018, however, exports dropped by an annual rate of 20%.

That big of a contraction for Brazilian exports is usually an indication of serious global trade distress. I’m sure the media will work in trade wars here, but there is no way that can account for these results. A dollar disruption, on the other hand, not only would, it has been behind each instance of global trade distress the last eleven years.

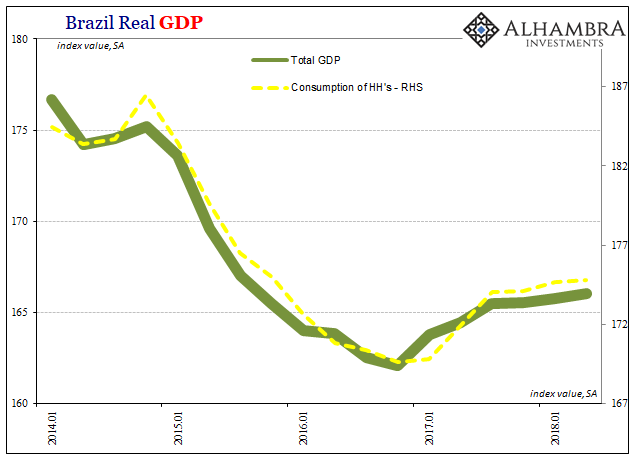

Household spending in Brazil was slightly positive, but has been essentially flat for a year now. Consumption is up just 0.4% in the three quarters since Q3 2017, and up only 3% from the bottom at the end of 2016. This despite HH consumption dropping by an incomprehensible 9% during the 2014-16 depression, the one that Banco officials in summer 2013 assured their people would never happen because of their monetary expertise.

To purposefully understate the situation, this is bad and it is likely just getting (re)started. It is therefore pretty understandable why the political and social situation is at times chaotic. People will put up with a lot, a sort of human societal inertia. They will even suffer an immense economic contraction and still look to the status quo for answers – but only if it seems reasonable the status quo might be able to offer any.

That’s what was so repugnant about the June 7 press conference. The consequences of central banker ineptitude are very real and at times so disastrous we just have no frame of reference for them. What you see above is a catastrophe, and all signs pointing to its unfortunate renewal, but one that isn’t unique.

The proportions are different in different places, but this global “L” is, well, global.

What you see above is not China’s economy controlling Brazil’s, rather it’s a pretty good reflection of the same force acting on both producing the same marginal ups and downs as well as the intensity and duration of each. Reflation #3 is unraveling and the reasons for its disappointing end are the same as those that came before it. There is no global growth because there can’t be. Central bankers don’t offer answers because they don’t have any. They don’t deliver solutions because they are the problem. They really, really don’t know what they are doing.

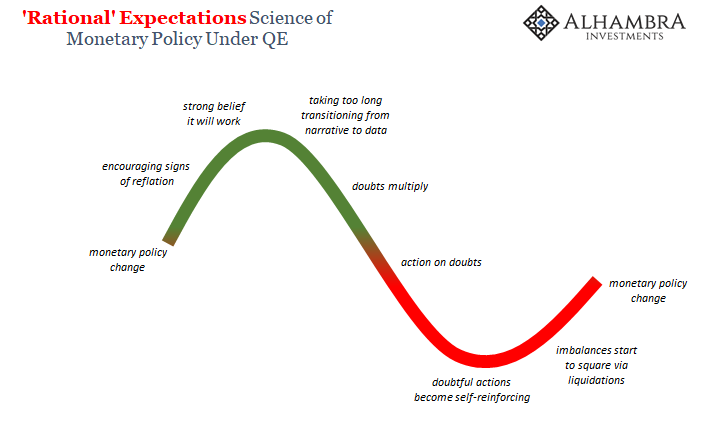

After enough happy, optimistic time reality sets back in. Everyone gets hooked on hopes for the “V” until it becomes clear enough we are all stuck with the “L.” At that point, the whole thing, not just Brazil, starts to sink back into the red (below).

Eurodollar (and Eurobond) markets turn ugly on the downslope of the green, rolling the global economy over piece by piece, domino by domino, so that increasingly dark economic prospects feed into more ugliness in “dollars” and so on and so on. Soon enough, it becomes self-reinforcing leading eventually to the entirely-too-familiar downside and downturn. Reflation is the only thing that is transitory, the artificial, intermittent interruption in otherwise background eurodollar deflation.

Q2 2018 doesn’t appear to have been an outlier, either. So far, Q3 isn’t shaping up any better. Adjusting for interventions, and not just those of braindead Banco central bankers, this current quarter may have been worse.

In each of the prior eurodollar episodes, Brazil’s economy has every time been the first domino to tip. It wasn’t quite falling over in Q2, though now we know it is already leaning and unstable.

Stay In Touch