Japan is the very model of fiscal irresponsibility. If ever there was a bond vigilante, surely they would have a Japanese address.

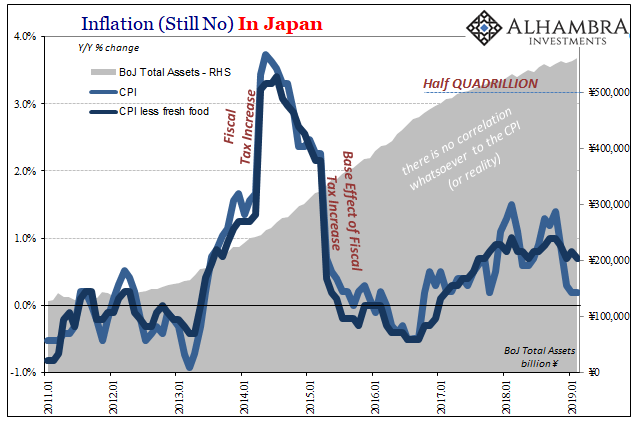

At the end of what was the Bank of Japan’s 133rd fiscal year, on March 31, 2018, Japan’s central bank reported total assets of ¥528,285,679,854,140. Of which, ¥448,326,107,324,120 was Japanese government bonds (JGB). Officials became increasingly confident these were sufficient balances whereby the bank’s top managers could openly plan an end to the programs raising them.

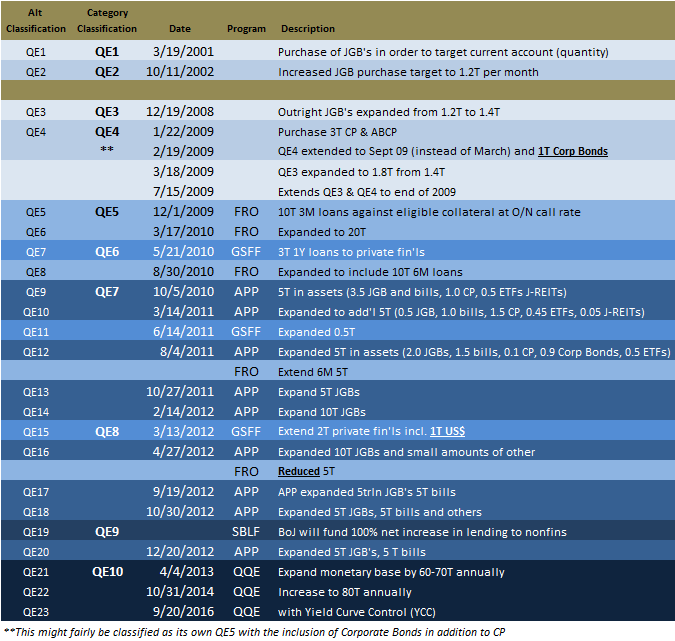

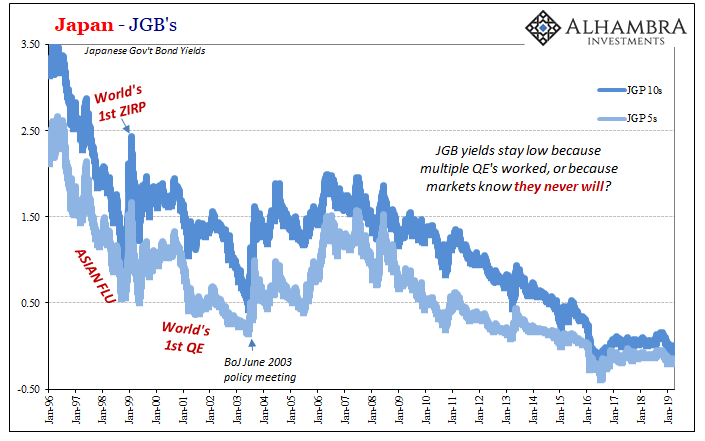

By my unofficial count, there have been ten distinct varieties of LSAP’s dating back to the first one in March 2001. Alternately, given how many times each has been adjusted, you can make the case how the Japanese have endured 23 QE’s over the years. It has been the last three, those that fall under the QQE label, which have absorbed almost all monetary policy focus.

Variety number ten, this QQE stuff, was the QE to end all QE’s, filling Paul Krugman’s mandate of “credibly promise to be irresponsible.”

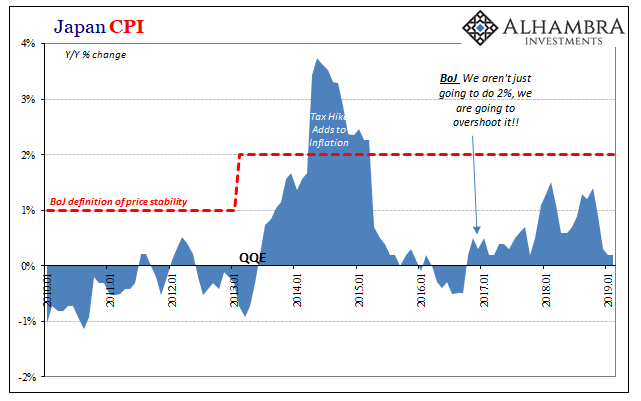

It was begun under much fanfare and promise in April 2013. Five years later, half a decade, BoJ’s Governor Haruhiko Kuroda last March said that was probably enough. Looking ahead a year to the end of fiscal year 134, Japanese officials were sure QE’s 21 through 23 were going to be conclusively judged sufficient by then.

Right now [March 2018], the members of the policy board and I think that prices will move to reach 2 percent in around fiscal 2019. So it’s logical that we would be thinking about and debating exit at that time too.

Fiscal year 135 began a week ago. At the central bank’s branch managers meeting in Tokyo today, Governor Kuroda maintained his usual optimistic forecast. The economy is, as always in the official view, “expanding moderately” benefiting from a “virtuous cycle from income to spending.” If you follow these speeches drawn from the official monetary policy documents, they say practically the exact same thing month after month, year after year.

Nothing ever changes along those lines. You might even start to think there is something else to all this.

Kuroda didn’t spend much time referencing BoJ’s recent downgrades to industrial production, exports, and, as everywhere else in the world, global growth.

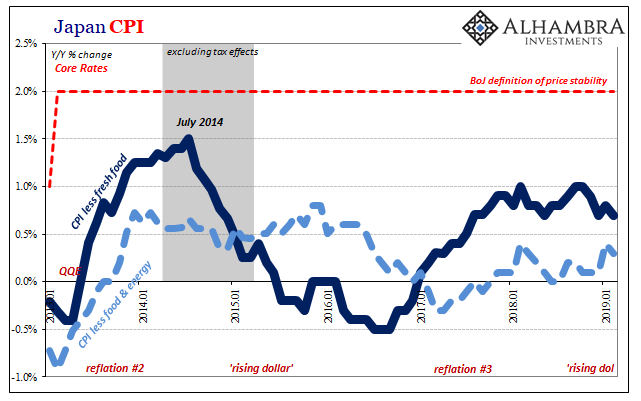

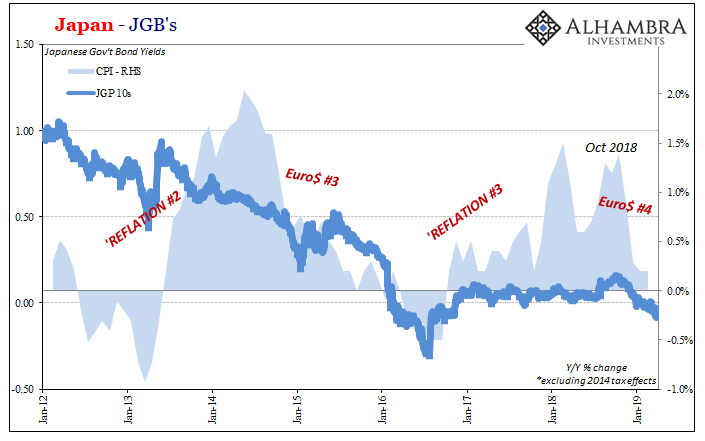

There is no longer any talk about an exit from QQE, whichever index number it might be recorded under. Inflation was supposed to have been near enough to 2% to make that possible. Instead, the CPI in January and February 2019 (the latest data available) gained 0.2% year-over-year in each. Right back near zero all over again.

The history of Japan’s bond market had said all along throughout Reflation #3 (as before) that Japanese officials were far more likely to be disappointed. Even as cannibalized as the JGB market has become due to so many government bonds and notes ending up in the central bank’s hands, hundreds of trillions on its balance sheet, what’s left of it still functioned enough to project a high probability for (continued) monetary policy failure. QQE, or QE’s 21, 22, and 23, didn’t really change perceptions.

If economic growth and inflation were meaningfully shifted by this credibly irresponsible monetary policy to the long-sought recovery paradigm, the bond market is right where it would show up first. You don’t want to be holding a low-yielding safety instrument, especially one issued by a government with the fiscal profile of Japan, on the verge of tremendous opportunity.

The entire point of QE23, this YCC stuff, was Kuroda’s imagination translating Paul Krugman’s orthodox philosophy. It was Krugman who in 1999 wrote his “liquidity trap” paper which provides the intellectual support for most if not all of what the BoJ is doing (there’s your problem!)

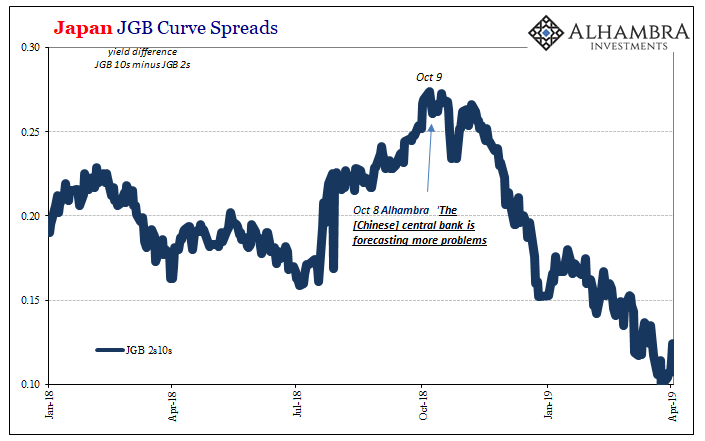

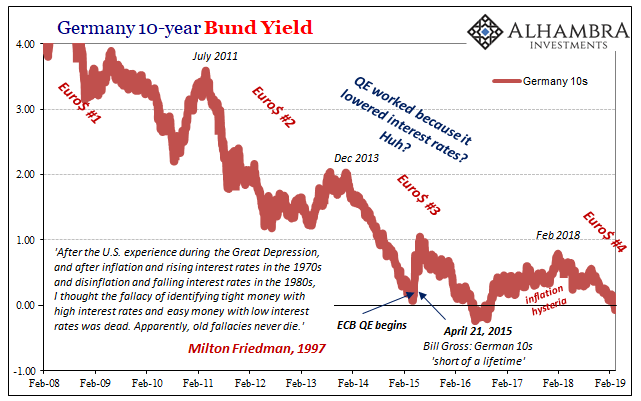

In other words, the point of YCC was for the central bank to promise to keep yields low even as recovery emerged. This was Krugman’s central premise, that the bond market will kill a nascent economic acceleration with rising interest rates before it ever gets started. And that tells you something about how Economists just don’t understand bonds.

If the recovery scenario is being priced into higher JGB yields, which it would be, investors are already taking into account those rising yields and seeing recovery anyway. That’s the nature of sustainability. The bond market has to judge the economic acceleration as of sufficient speed as well as robustness; that’s what makes a recovery a recovery in the first place (this applies currently in America to those who think fed funds 241 bps has choked off the US one).

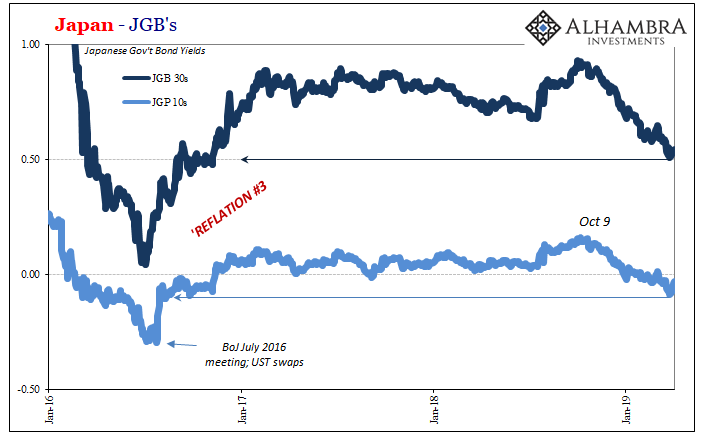

Kuroda and his fellow Japanese officials in September 2016 mistook Reflation #3 for Recovery #1, and therefore began seeing “globally synchronized growth” as the endgame. The bond market, as you can see above, didn’t make that mistake – YCC or not.

The only time when yields appeared close to a breakout was last summer. And even then, it was far more modest than it was made to be under the death throes of globally synchronized inflation hysteria.

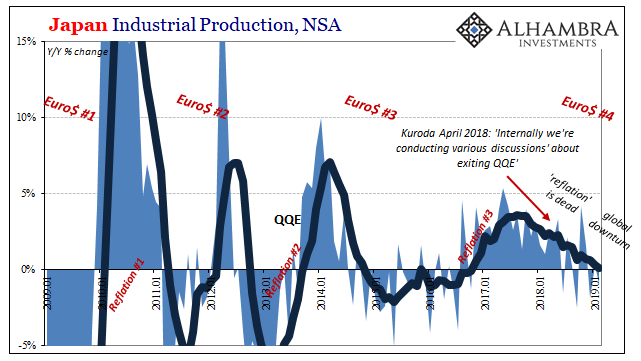

In fact, while all that was taking place in 2018 there were numerous escalating warning signs which uniformly indicated the opposite case from recovery and acceleration. Japan’s Industrial Production, for example, was perhaps the best one – for the whole global economy, not just in Japan. Japanese IP historically has been among the most accurate reflation/deflation bellwethers out there – and it is validating the JGB market’s persistent skepticism with an already pretty visible downturn emerging.

Kuroda and his gang (including Krugman) don’t understand bonds, therefore they keep dismissing the pessimistic signal embedded within these persistently shrunken yields. Those low yields are not the result of central bank bond buying, rather they result from the failure of central bank bond buying (German yields providing the cleanest example of their basis).

Because of this, there are no bond vigilantes at least there aren’t any possible right now. First comes recovery and the very much related removal of liquidity fears – the specific monetary concerns and overall economic pessimism which fully override all considerations of fiscal imbalance and long-term deficits/debts. Only when those are solved will the vigilantes be reconstructed and let loose.

We don’t need central banks to hold down interest rates or even think they should try. In fact, we should want officials to shoot for bond market destruction; that should be their only goal. If recovery shows up there, the first taste of fiscal vigilantism, get out of the way. The economy will have by then already made it to the promised land.

Rising interest rates are not something to fear, they are the checkered flag waving you to the finish line. The most effective yield curve control ever conceived is continued economic failure. You don’t really need 23 QE’s to see this, but apparently that’s how thick Economics dogma has become.

If Kuroda (like any other Economist) actually understood bonds, he’d have realized he never had a chance. Not only would it have saved him fiscal year 135’s QQE embarrassment, it might have even told him to do something else. As it is, the economy going the wrong way for a fourth time in the last decade, JGB’s are betting the central bank will be stung enough by this economic downturn for QE24 if not a new QE-type 11.

A glimpse at our shared future.

Stay In Touch