It was one of those signals which mattered more than the seemingly trivial details surrounding the affair. The name MF Global doesn’t mean very much these days, but for a time in late 2011 it came to represent outright fear. Some were even declaring it the next “Lehman.” While the “bank” did eventually fail, and the implications of it came to be systemic, those overly melodramatic descriptions actually served to downplay the event in public imagination.

The world didn’t outwardly fall apart when MF Global did, so it must not have been worth remembering.

Underneath those histrionics was hidden the last hurrah, of sorts, for what had been left of the pre-crisis monetary system. The first Global Financial Crisis (GFC1) wasn’t really subprime mortgages, rather those the symptom of monetary and banking evolution gone astray; gone insane.

There’s too much detail to get into here, which is why nearing the ten-year anniversary of its demise a review of MF Global still might end up being useful.

The rising eurodollar before August 2007 had been really nothing more than the amalgamation of wholesale plus accounting, those as sometimes counterintuitive and incredibly complex money creation combined with the necessary intermediation role played by the banking system for the real economy.

And it was this method MF Global had employed, and would continue to employ even after all that happened in 2007 and 2008.

Where those all intersected most favorably was in the various off-balance sheet arrangements. There were SIV’s and SPV’s which were constructed to appear remote, along with more immediate transactions like something called repo-to-maturity. Basically, banks doing things, profiting from those things, but making full use of limited balance sheet capacity in order to leverage them most thoroughly.

It was that last one which brought down MF Global in October 2011. I described the absurd messiness just days thereafter:

The transaction in question was a “repo-to-maturity” financing deal, collateralized with the troubled sovereign European debt that everyone has been talking about in the past few days. What is particularly striking about this is that a “repo-to-maturity” deal is accounted for as a sale, meaning that what is essentially an ongoing collateralized loan is, surprise, hidden off the balance sheet. Maddeningly, MF Global likely booked a profit up front at the transaction’s consummation using obviously faulty mathematical expressions of those “reasonable” expectations of profit, thus avoiding the need to post any liability to the balance sheet.

This makes a lot of sense, then, in why FINRA “demanded” it change its capital treatment of the transaction. Though it was “properly” accounted for according to convention, the risks of collateralizing a loan with questionable debt means that MF Global has ongoing liquidity risk attached to it. As the value of the European debt collateral is questioned, or falls, the lender/cash owner counterparty will ask for additional collateral posting as it applies a stricter haircut to that original, troubled collateral. So, even though this transaction has fully cleared MF Global’s books, the company is still on the hook should it be required to post additional collateral or cash (which ended up with the company in bankruptcy, just like AIG).

The “bank”, really a glorified hedge fund, speculated on PIIGS bonds in Europe, intending to profit from the spread between what it could borrow using those bonds as collateral and the rising coupon rates paid by the troubled governments to anyone willing to buy their debt. The bet here seemed a no-brainer, not with the almighty ECB pledging outright to stand behind these securities (OMP, SMP).

MF Global booked a huge up-front profit when the trade(s) was realized, as if all the cash flows to maturity happened all at once, and then repo-ed the bonds as collateral to keep it all funded. Only mark-to-market changes would have to be run through the income statement, though none were anticipated (thus, limited spare collateral).

However, once the value of those bonds began to tank in 2011 even with the ECB’s “support”, suddenly, though these actual PIIGS securities weren’t included on MF Global’s balance sheet (remember, only the calculated profit from the trade was), the firm was still on the hook for collateral calls (JP Morgan again) when haircuts were inevitably and unfavorably adjusted against the position(s). At some point, just like AIG or Bear, they simply (quickly, as it turned out) ran out of spare collateral (including transferring customer assets offshore to repledge, à la Lehman) to cover the difference(s).

It was yet another powerful reminder, and a poignant post-2008 one, of the unfixed risks of this farfetched eurodollar way of doing money and banking business. Governments didn’t need to write regulations to reign in risky activities, beginning with Bear (and before that failure, Bear’s hedge funds which failed in the Summer of 2007 for many of these same reasons) the banking system began to finally appreciate the stark consequences of previously unforeseen liquidity (not credit) risks.

Governments and central banks merely demonstrated time and again how little their “support” would matter.

Lending is not just some idyllic depository function; intermediation is absolutely crucial. Going back to ten years ago:

Intermediation is supposed to be about matching the wider (real) pool of savings to worthwhile economic projects that have a real, productive impact on the real economy. MF Global’s repo-to-maturity transaction cannot be fairly classified as real intermediation since the firm knowingly advanced credit to an economically unfeasible obligor with the expectation that the price would never reflect that reality (how’s that for enhancing price discovery). This crystallizes, I believe, just how far the financial system has moved away from real intermediation and reflects the biggest part of the real problems in the real economy – money is no longer productive in economic terms and has not been for decades.

It’s not that we want or need more MF Global’s and AIG’s; no one would seriously argue that the pre-crisis way of doing things was preferable. Rather, it was never considered how the world would cope in the absence of this way, or any other way, of doing money.

Monetary policy, most of all, merely bet on convincing the world everything would just go back to “normal”, if a more responsible kind of normal when combined with Dodd-Frank and Basel III or whatever.

The eurodollar had essentially intertwined if not thoroughly combined the money creation function with the intermediation function. In its early days, that was fine to overcome Triffin’s Paradox. By the Great Inflation, already serious questions whether this was a good idea.

Hopped up on the Volcker Myth and step-up to the mature eurodollar system, when the world advanced past the point in 1995 (RiskMetrics) and even the 1997-98 Asian Financial Crisis (regional dollar shortage), the money creation function went nuts and eventually just overwhelmed the intermediation function to the point that this way of doing money and intermediation seemed to make sense to a lot of otherwise smart (if unwise) people.

Subprime mortgages merely the clearest symptom of these extremes. Ben Bernanke (wrongly) saw this as a global savings glut.

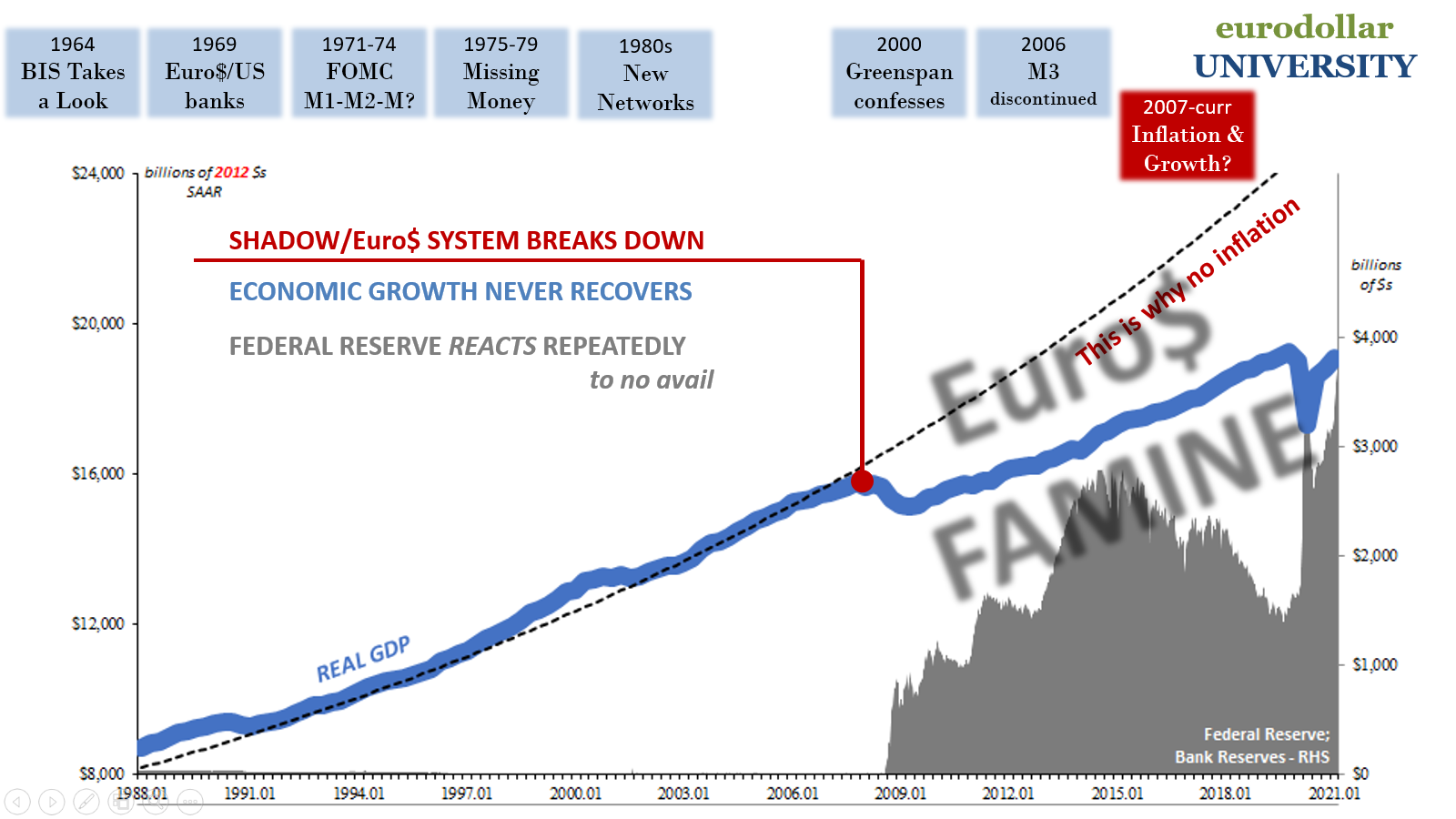

The breakdown begun in August 2007 impaired the money creation process (wholesale plus accounting, off-balance sheet and the like) but as that function reversed this did not restore the intermediation function. On the contrary, it’s even worse since the pendulum swung all the way to the other extreme – as noted last week.

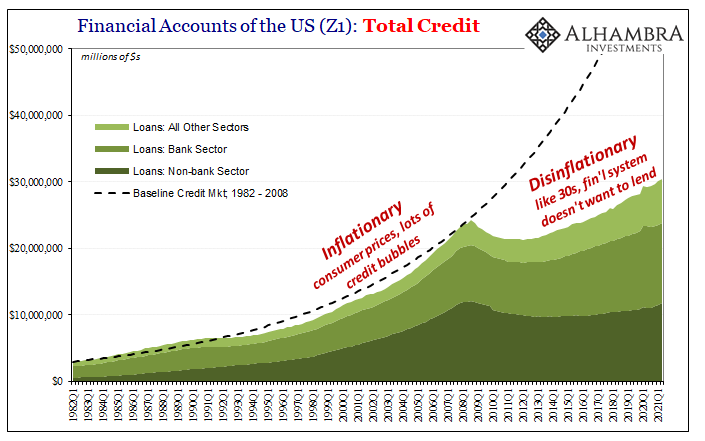

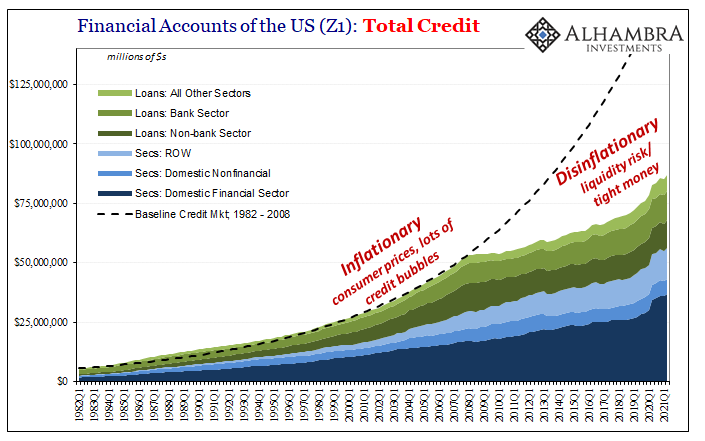

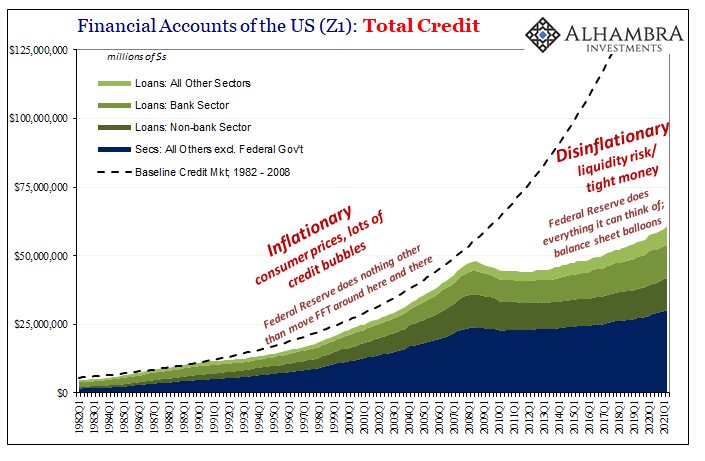

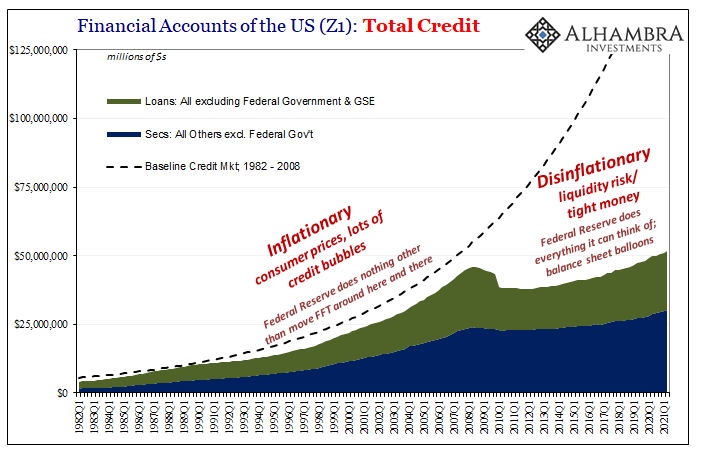

Whereas too much eurodollar, off-balance sheet money before had meant little intermediation and therefore left the global system to take on way too much credit of all kinds, such as subprime mortgages, in the post-crisis era the collapse of the money creation function has meant for the intermediation function leaving the world with a financial system doing way too little.

MF Global’s 2011 downfall represented one of the last holdouts suffering the same fate as the more-famous others, thereby putting a final nail in what was left of this way of money/credit creation.

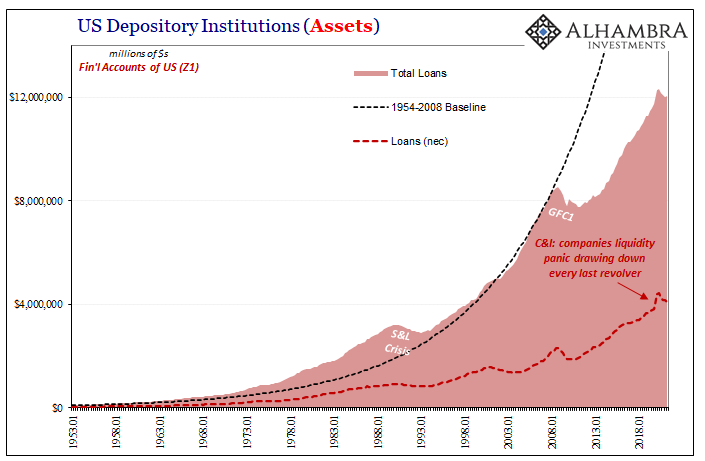

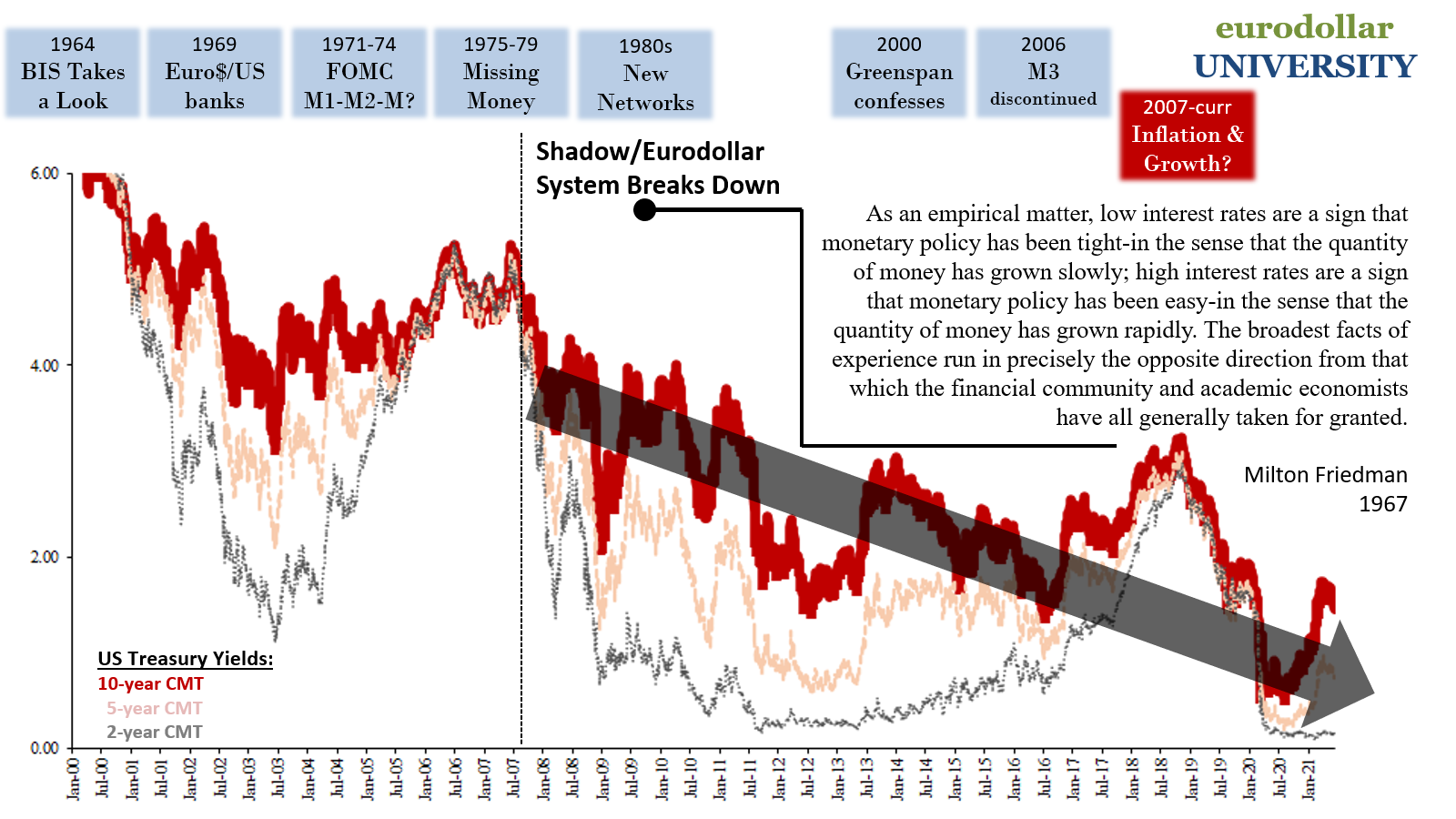

There’s neither money nor credit and so intermediation is left for nothing other than to prefer only safety and liquidity. Lending has flopped and more than that it has stayed flopped no matter what QE or level of bank reserves in any place.

Using bank-only data (above), however, understates the lack-of-lending problem (below); even though this stuff like what MF Global had been doing was off-balance sheet, in every functional and meaningful way these off-balance sheet structures and transactions were nothing more than what had once been a highly efficient extension of bank balance sheets. As bad as the bank data already proposes, you won’t actually get the full measure of this impairment without looking at the problem more broadly.

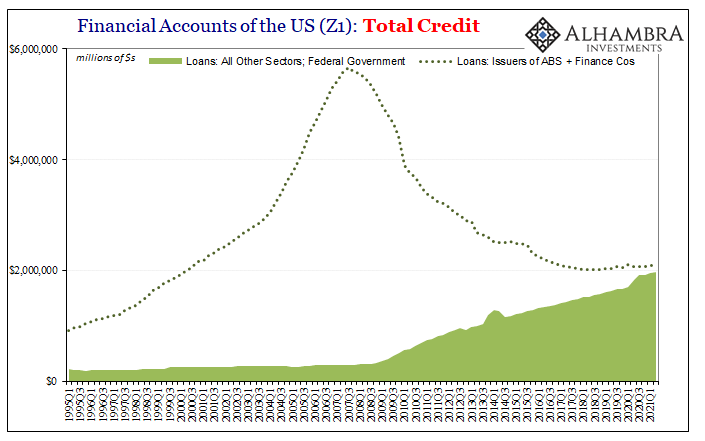

As money creation and intermediation have both reversed, we see this most clearly in data like that for ABS or Finance Company lending; each have utterly collapsed and have never been replaced, both relied heavily on off-balance sheet natures.

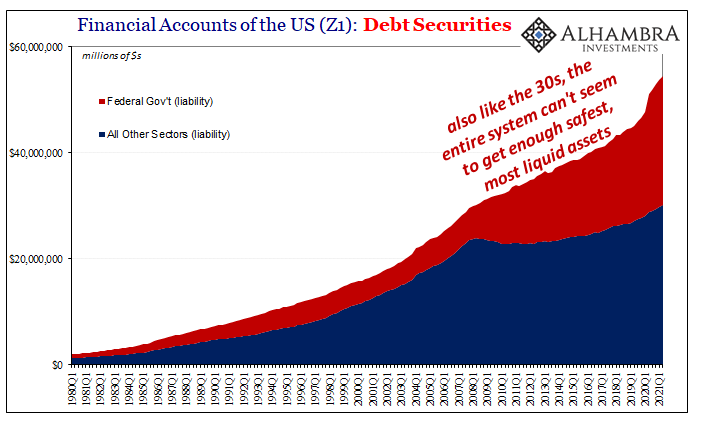

This has left only governments to try, and fail, to make up the difference. The official sector has created its own loans at times (see: below), and governments have certainly borrowed (also below) in the absence of money creation and intermediation (their own shot at intermediation via federal redistribution). These are neither efficient (wasteful) nor anywhere close to sufficient in size to make up what’s now an incomprehensibly large gap.

Without private money creation and intermediation, lending, basically, there’s no way to get back to growth and inflation; the very reason why each inflation hysteria comes up only short given enough time as well as why no one can answer for this “puzzle.”

Everyone is told to focus on what they can see in the form of bank reserves or UST issuance rather than what they “can’t” which is what remains for real monetary forms in the world (not enough of it).

Because Economics had long ago abandoned all monetary scholarship, when that crisis came no one knew enough about it – what really was going on – to appreciate how that had meant two massive, systemic problems.

The collapse and breakdown was one thing, but then what? QE and bank reserves were no real answer to the crisis nor its aftermath.

We never would have wanted more MF Global’s or Lehmans, or to restore them once they fell, but the truth is global growth had come to depend upon the way they did their money and intermediation business no matter how unstable we today know it had been. In one respect, it was a good thing that the banking system expunged such risky stupidity, but it has been utterly tragic in that nothing has replaced those capacities.

Thus, the Great Eurodollar Famine:

One key reason is QE: not that bank reserves are effective money or some substitute for what MF Global and others used to do, rather because they are not and were instead designed only to manipulate expectations and emotions, and they’ve lulled the public into a false monetary sense of an overabundance. People are utterly confused as to what should be, once you get past all the complications, incredibly simple and straightforward.

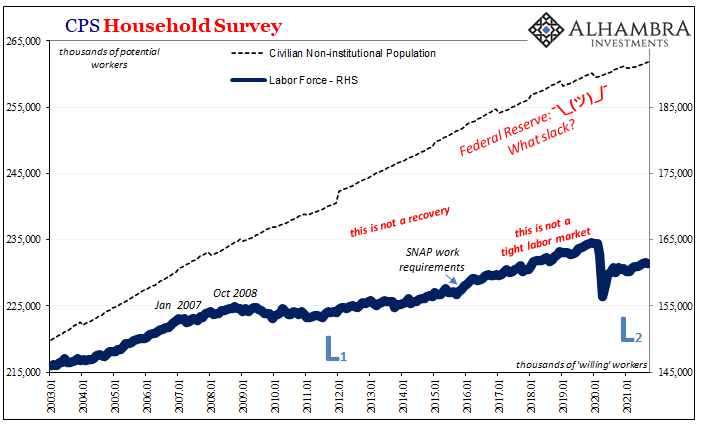

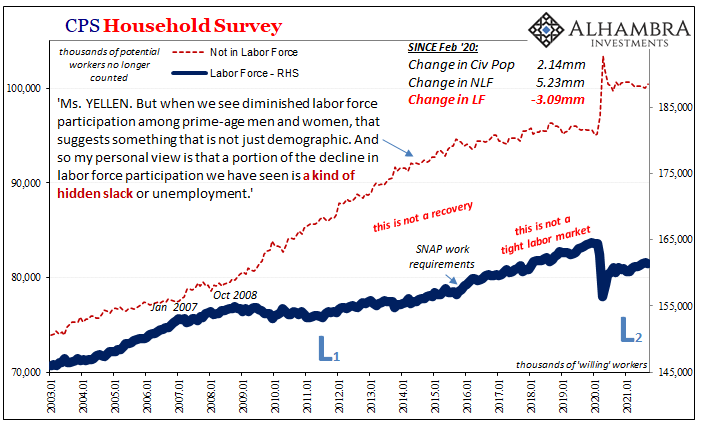

The money creation function remains entangled with the intermediation function to this very day, and therefore both are suffering the consequences; leaving the global economy to suffer systemically, persistently under general disinflation and the various real economy decay which comes along with it (especially the labor market and not just in the US).

Despite everything that has happened since last year, nothing has changed in this regard (see: everything above).

Stay In Touch