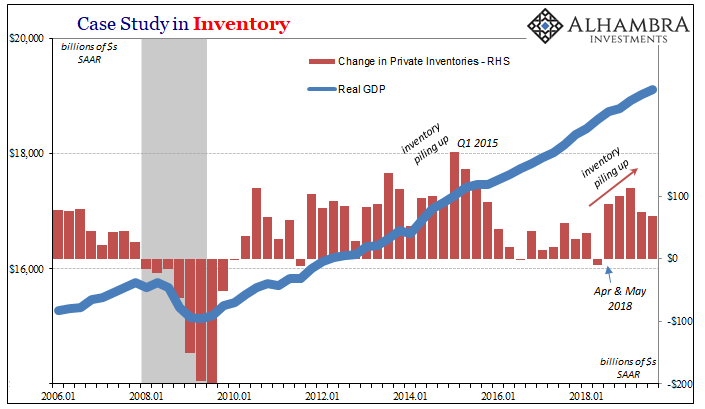

What typically distinguishes recessions from downturns is the inventory cycle. Even in 2008, that was the basis for the Great “Recession.” It was distinguished most prominently by the financial conditions and global-reaching panic, true, but the effects of the monetary crash registered heaviest in the various parts of that inventory process.

An economy for whatever reasons slows down. That leads to inventory piling up across the various levels of the supply chain. Most businesses will remain patient and work through a material glut as best they can – so long as they continue to be relatively positive and optimistic that their customers aren’t more durably impaired.

If they begin to believe their customers aren’t coming back, not only do they cut back on new orders for goods, therefore tanking production, they also start laying off some of their workers (while producers have to, too). And it can become self-reinforcing, where the layoffs lead to lower consumer spending and then more layoffs and fewer production orders and even less sales and revenue.

That’s really what made 2008 so bad; in sight of so many global financial problems, businesses quite rightly responded to them as signals of real nasty times ahead. As such, with inventory already on-hand, they went to drastic even obscene measures of adjustment (with many corporations taking things a step further in the negative given their dwindling liquidity positions and being unable to count on the banking system for normal everyday things like funding for working capital).

In many ways, that’s all monetary policy really is – forget the stuff about money and effective liquidity. A rate cut is intended to be a signal to businesses (and consumers) directly. It’s not really about banks and money, and it doesn’t really matter how it’s supposed to work in banking, policymakers want to interrupt any negative feelings about the current state of the economy business owners and managers might be experiencing. To give them something positive to hold onto while those owners and managers decide whether or not to pull the trigger on more radical inventory cycle actions.

Nobody is supposed to ask why a rate cut is a positive; we are just supposed to take it on faith, and policymakers take it on faith that we all do.

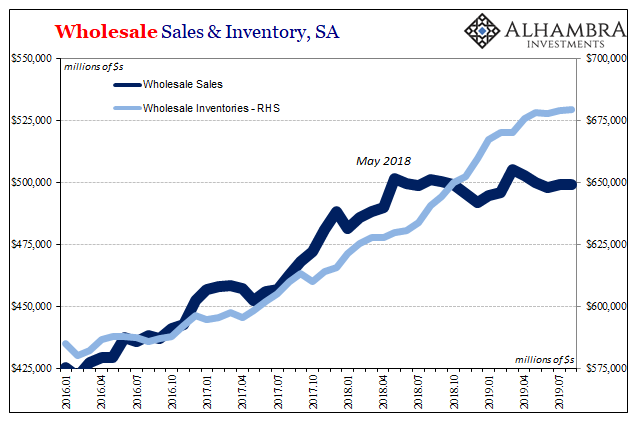

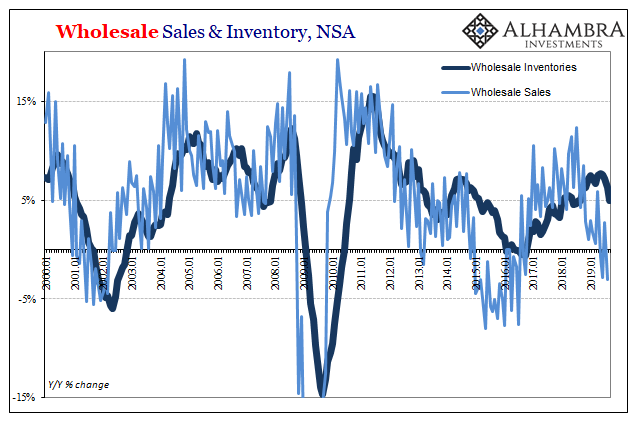

What we know from today’s GDP report, outside of the headlines, is that the inventory continues to pile up. Step 1 in the cycle.

It isn’t quite the same rate as it was in 2018 as spending began to slow down, but the GDP estimates are pretty consistent with other figures recently suggesting businesses are only now starting to look upon inventory levels more suspiciously.

For that reason alone there would be rate cuts.

What Jay Powell is hoping is, again, that the business sector will be buoyed by them such that they remain patient and work through the front part of the inventory cycle without reverting to the more extreme and harmful macro steps coming in the back end of it.

And that’s where Powell is likely to be most disappointed. Recent data already suggests that businesses have moved a little further toward that second part of the inventory cycle, the labor market piece of it (capex, too). While they’ve been somewhat patient on inventory, there is evidence piling up they’re getting itchy on staffing.

The BLS payroll numbers have already shown a major slowdown in hiring and employment growth – something approaching a hiring freeze. That data is being corroborated by additional estimates like JOLTS as well as outside, private data. Such as:

A measure of hiring by U.S. companies has fallen to a seven-year low and fewer employers are raising pay, a business survey found.

Just one-fifth of the economists surveyed by the National Association for Business Economics said their companies have added to their workforces in the past three months. That is down from one-third in July. Job totals were unchanged at 69% of companies, up from 57% in July. A broad measure of job gains in the survey fell to its lowest level since October 2012.

Again, that’s consistent with the economic outlines already laid out by the BLS – not including the unemployment rate. As an aside, it is interesting how hard it is for members of mainstream media outlets to come to terms with what to them seems to be a contradiction: these indications of a weak and weakening labor market at the same time the unemployment rate keeps falling to new 50-year lows.

As a result, the article quoted above makes a blind (and somewhat humorous) stab at resurrecting last year’s absurd LABOR SHORTAGE!!!!

Hiring may also be slowing because the unemployment rate is at a 50-year low of 3.5%, and many companies are struggling to find enough workers.

Try as the author might, he can only at best qualify that 2018-ish stance; “Government data shows that companies are posting fewer available jobs, suggesting that demand for labor is weakening, as well as supply.”

While a curious detour in their analysis, it does point to something relevant. At best, the Fed can only hope that current conditions are, let’s say, less clear than they might otherwise be. Businesses right now in the thick of a potential inventory cycle might want more clarity on where things really stand, but so long as the Fed can pound a contrary message of rate cuts and the unemployment rate (with a financial media only too willing to help) that’s their best chance of avoiding the whole of the inventory cycle.

And that’s just what the FOMC is attempting to do.

That’s hardly a good chance outside of academic circles where monetary policy as a means to manipulate expectations is looked upon as a solid way of doing things. Something like this might’ve worked in 1995 or 1997 when the “maestro” Alan Greenspan was in his absolute heyday and the myths and legends about his control over the fed funds rate were largely unopposed.

Over here in post-crisis reality, Powell just doesn’t get the same leeway. Nor does he deserve it. While at the same time policymakers are counting on rate cuts to provide some kind of anchor for positive sentiment, even the least aware layperson can’t help but notice how they’ve gone this year. I wrote earlier:

But instead of renewing the “tightening” trend for monetary policy, poor Jay Powell has to try to explain now three rate cuts where that was supposed to have been. Even the most optimistic among you will have to ask what has happened to the unmistakable second half rebound which was going to right the economic ship and put everything back on track (including and especially the BOND ROUT!!!)

At first, back at the end of July, the single rate cut was going to be one and done. Then just the two even though the second one was stepped all over by whatever it was in the repo market (still no one will say). And now three.

As Powell keeps backtracking with each cut, as he keeps changing his mind about them, the risks only rise that business leaders will change theirs about the inventory cycle. If, as more data keeps suggesting, they haven’t started to already.

Stay In Touch