Since it is an employment report Friday it seems appropriate to continue on the theme of dysfunction in the labor market. I’ve already covered the more recent occurrences of the structural change post-2009, here I want to examine the foundation for this paradigm shift.

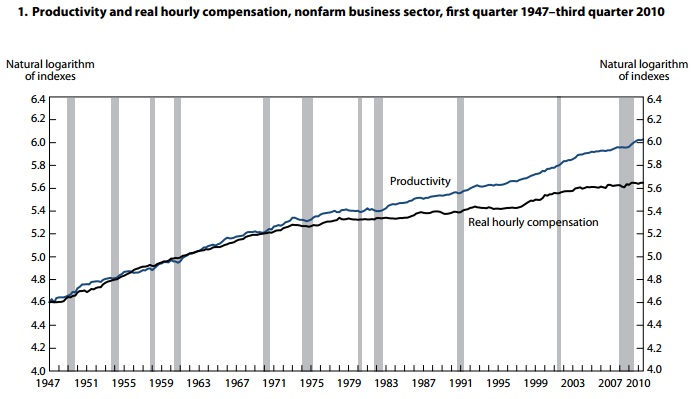

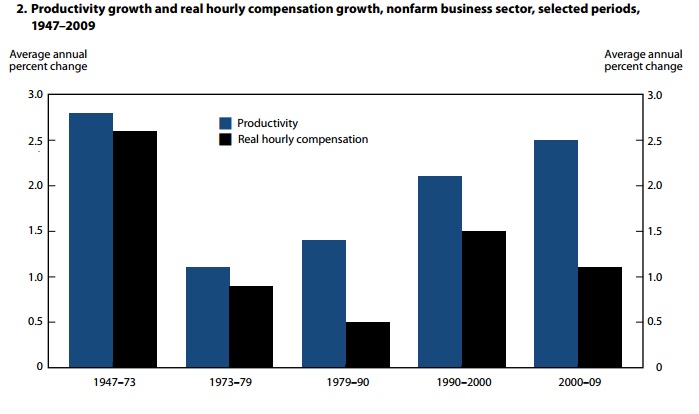

As part of its academic arm, the Bureau of Labor Statistics publishes a monthly review of labor-themed topics. In January 2011, authors Susan Fleck, John Glaser and Shawn Sprague calculated what they termed the “compensation-productivity gap”. Visually, it is very easy to understand both the problem and the implications.

Since the latter half of the 1970’s, business productivity has advanced far more quickly than real hourly compensation, leading to a decline in “labor’s share” of national output. Or, on the flipside, companies have been able to increase profitability at a rate greater than labor costs. The gap has only grown larger with time, becoming an even wider gulf in the 2000’s.

Any economic system set up in this manner eventually comes to a circulation problem – how to keep corporate revenue increasing while simultaneously “depressing” labor incomes. The paradigm as represented in the gap is one where business revenue expands faster than wage incomes, turning the old Henry Ford scenario completely upside down (“make the best quality of goods possible at the lowest cost possible, paying the highest wages possible.”) Of course, we can assume that domestic business held firm to that axiom, but other indications heartily disagree.

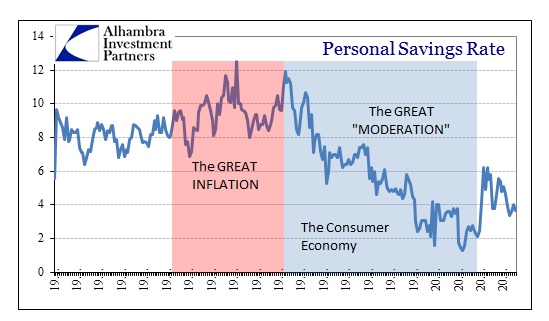

First and foremost, the behavior of American consumers argues that wages did indeed diverge from productivity in a very real and tangible manner. Yet, the economy continued to progress, even thrive in the so-called Great Moderation. However, this disparity is bridged almost exclusively by new monetary paper, as it would have to be absent a huge increase in export activity or some other means outside a relatively closed system. Since the economy is circular, wages have to at least somewhat reside close to corporate revenue since workers are consumers. Any difference between them is bridged by productive investment of true capital (profits).

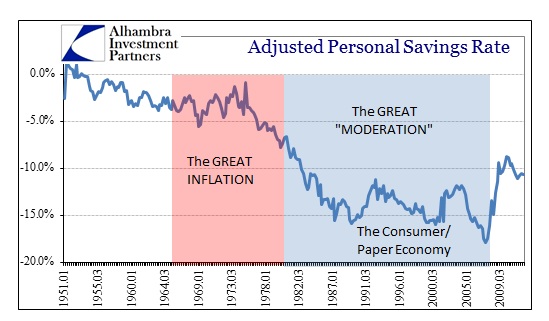

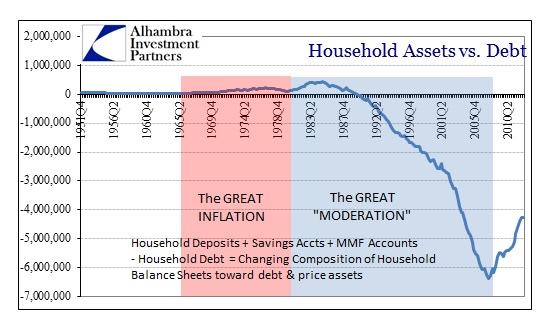

Instead, what we see is not new capital being deployed, but new paper being added. That meant monetary imbalance and inflation (both types, asset and consumer, proportional to the central bank impetus to control the economy). Coinciding with the compensation-productivity gap, US consumers suddenly shifted preferences away from savings. The funding means to accomplish this feat, given the income disparity where savings are accumulated in the upper incomes, is a total embrace of debt and credit. If we adjust the savings rate for asset income, the divergence between earned income (real wages) and personal spending widens with the productivity gap.

The effect on household balance sheets bears this out.

The really interesting question is which is cause and which is effect. Did the compensation-productivity gap first develop, forcing households to deal with the lack of income; or did the growing financialization of the economy reduce wage pressures to where corporate profits could grow so much faster than wages?

There is another factor to consider here, namely the asset bubbles and corporatization. As monetary imbalances wound their way into asset prices, particularly in stocks in the latter 1980’s forward (again, coinciding with the greatest disparity between income and productivity), that had to have played a role in setting corporate behavior. The rapid ascent in stock values, as management compensation became increasingly tied to that metric of performance, certainly focused corporate operations on the bottom line like never before. In a large, marginal sense, the dot-com bubble may have been a very real depressing factor on American wages.

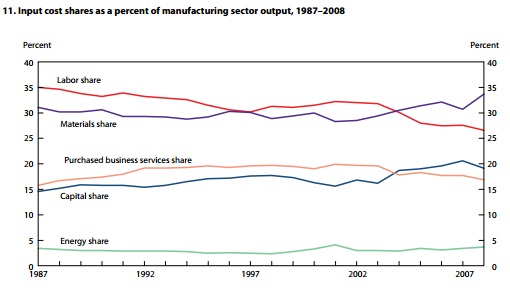

Some are tempted to place blame on globalization, but I would submit that the narrowing focus on cost cutting and profitability during the time period was actually a (the) primary force driving globalization in the first place. That blends perfectly with what occurred in the 2000’s, as monetary policy finally began to openly devalue the dollar and drive commodity prices upward. In terms of profitability, any corporate effort to manage costs had to then adjust to both labor’s share of corporate cost and as well as materials. That meant, among other efforts, seeking out still cheaper labor.

That would account for the 2000’s having the widest gap between productivity and wages. And there was the heaviest monetary imbalance attempting to keep the now-large divide from sinking the economy. The monetary intent was not to close the gap but to fill it, as houses were turned into ATM’s in just enough proportion to maintain the economy on a tepid growth path. In that pursuit, household balance sheets, along with business’, became severely impaired, setting up the structural shift that is still in place today.

I think what the compensation-productivity gap really shows is the degree to which economic growth in the past thirty to thirty-five years has been artificially boosted by paper rather than true capital. I would further argue that the original divergence, occurring during the Great Inflation, was itself derived from monetary imbalance. The first half of that period saw inflation based on wage pressures, but the second half, leading into the 1980’s was all about commodity prices and feedbacks.

One of the prime feedback channels was growing financialization due to that monetarism. The rise of the financial economy, indeed the eventual domination of the financial economy, dovetails with the gap perfectly. This emphasis on stock prices and profitability (in the “per share” sense) leads to exactly this kind of disparity because of the disproportionate focus on costs and favoring largely financial “investments”; that means more stock repurchases than new factories that actually create jobs and higher wage opportunities. It also concentrates income upwards, as share repurchases and dividends recycle “money” not into wages but shareholders. Those expecting this “wealth effect” to create a virtuous economic cycle have instead seen the debt substitute create the opposite.

If monetary policy had not taken such a turn toward abstraction and central control in the 1980’s, it is entirely possible (warning, counterfactual) that the compensation-productivity gap would have closed on its own – largely through a lower economic growth trajectory. That may seem undesirable, but in comparison with the bubble economy of the 1990’s-2010’s it might have presented at least a more stable alternative.

Even if monetary policy did not cause the compensation-productivity gap, there is little doubt that it played a primary role in nurturing it and fostering its widening (intentional or not is another topic). The question now becomes one of how corporations, or more precisely their stock prices, can survive any reversion to the productivity mean. Without the debt supplement we see an economy that failed to recover from the Great Recession and is retrenching again. That is trying to force productivity lower (rather than increase wages) through lower revenue.

Corporations have so far responded by further appealing to cost management (depressing wages) and buying back more stock (reducing the creation mechanism of new higher wage jobs). Monetary policy explicitly aids this process, but can it last much longer?

Click here to sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

“Wealth preservation and accumulation through thoughtful investing.”

For information on Alhambra Investment Partners’ money management services and global portfolio approach to capital preservation, contact us at: jhudak@4kb.d43.myftpupload.com

Stay In Touch