The FOMC statement for the July-August 2018 policy meeting exceeded expectations once more. It’s difficult for the Committee to continually do this since the whole point of these things is to downplay all expectations. The goal is to make everything seem boring and uninteresting, if the Federal Reserve is doing its job.

But they are always interesting because nothing over the last decade has gone to plan. Not one thing. Even now, the economy is supposed to be booming (“strong” in the updated official language) which should be as uncontroversial as any characterization since maybe the 1990’s. And yet.

These policy statements are taking on that familiar air of uncertainty again. There’s now talk about overseas things, though unlike 2015-16 they aren’t as nonspecific as “overseas turmoil.” Trade wars have entered the official guidelines in a way that Jerome Powell wishes they hadn’t. There is always uncertainty at any given time, but the constant intrusion of big things is beyond the usual noise.

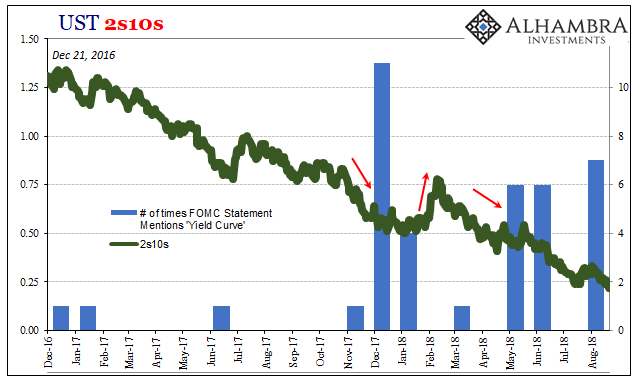

We know it is big, this something, by what the FOMC spends it time talking about – and writing down in its official statements. The words “yield” and “curve” particularly together have notably become a regular feature.

When the yield curve was last at its steepest, for this reflation cycle anyway, it was hardly noticed. The 2s10s jumped to their highest on December 21, 2016. That was amidst the full weight of Reflation #3, and so we would expect the curve to simultaneously move higher nominally while also steepening in the process (as had happened during Reflation #2 in the middle of 2013). No need, really, to talk about it when it’s doing what it’s supposed to.

But it never really got all that far to begin with. Even at that moment in 2016, it was still a shriveled husk.

Since then, the yield curve has been pressured by competing views. The short end moves with “rate hikes” not because investors might agree with the FOMC’s reasons behind them, but because the FOMC offers monetary alternatives where they pay interest set for non-economic reasons. The long end, though up nominally from the lows in 2016, remains conspicuously stifled despite all that.

The flatter it goes, the more the FOMC has been talking about it. That seems reasonable; people often talk more about what’s on everyone’s mind at a particular period in time.

But in this case, it would only make sense if at some point in 2017 the Committee or any of its officials had come out and said, “hey, we expect the yield curve to flatten next year”; or, more accurately, “we expect the yield curve to continue to flatten in 2018.” They never said that because it wouldn’t have made any sense.

A strengthening economy in this bond market is a very simple thing, so simple an Economist could understand it: BOND ROUT!!!! I don’t mean the ones that we heard about all last year and the early part of this year, those that for a time dominated the media but only in the future tense.

A truly strong economy will be foretold by a bond massacre in the present tense.

Again, this is why the FOMC has been talking about the yield curve. It is the bond market laughing in their faces about this “strong” economy – starting with the reasons why it will never really be strong (risk). It is therefore incumbent upon them to say something, anything about why it isn’t going as planned.

At their last meeting, they came up with this:

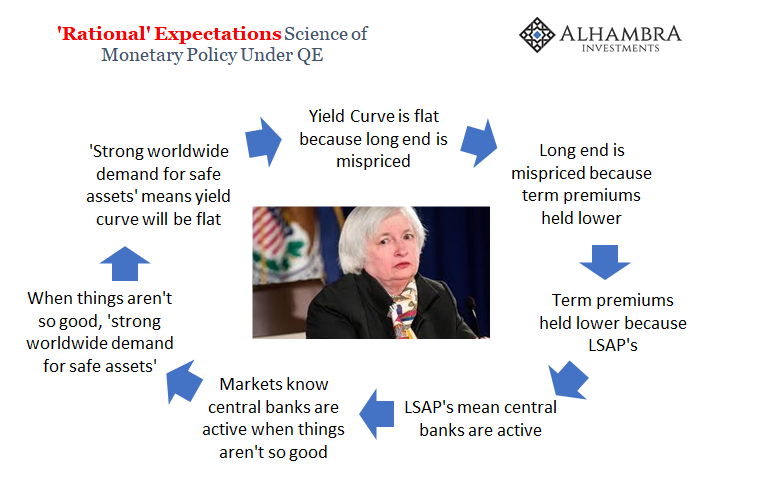

They suggested that policymakers should pay close attention to the slope of the yield curve in assessing the economic and policy outlook. Other participants emphasized that inferring economic causality from statistical correlations was not appropriate. A number of global factors were seen as contributing to downward pressure on term premiums, including central bank asset purchase programs and the strong worldwide demand for safe assets. In such an environment, an inversion of the yield curve might not have the significance that the historical record would suggest; the signal to be taken from the yield curve needed to be considered in the context of other economic and financial indicators. [emphasis]

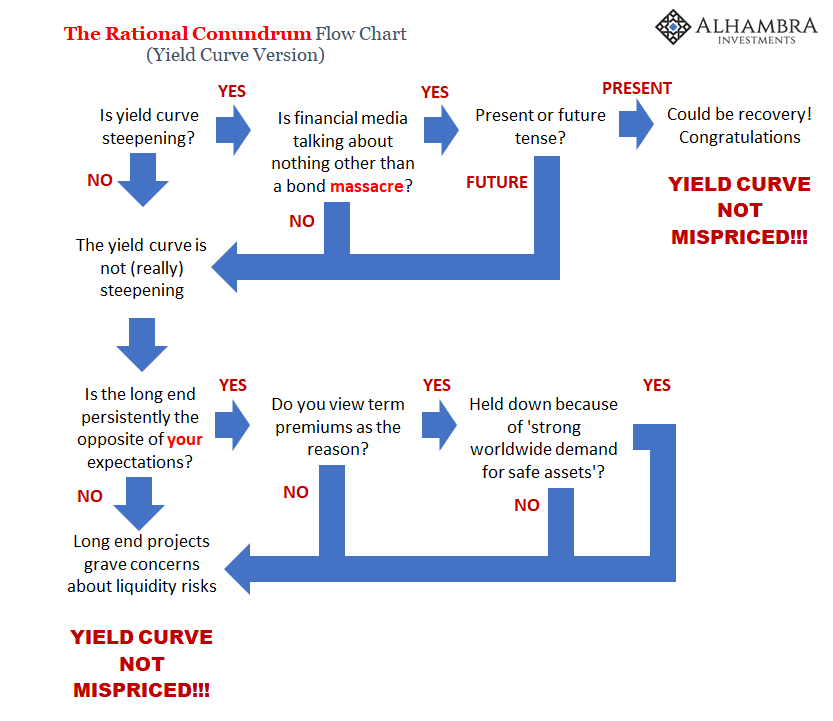

Let’s follow through and unpack what they are (trying to) saying (say). The long end of the curve must be, in their view, badly mispriced. The reason it is mispriced, they believe, is because central banks are buying up securities (not just in the US, they mean global bond markets) and because of the “strong worldwide demand for safe assets.”

Central banks tend to buy up assets (LSAP’s) when things aren’t so good, and the “strong worldwide demand for safe assets” would tend to agree with that assessment. So, how is the long end mispriced? Even if you buy the whole term premium thing, which is ridiculous, even on their own terms the FOMC is trying to discredit the long end by using the reasons the long end disagrees with them?

The yield curve is flat and therefore the long end is mispriced because it is correctly pricing these things. You would never associate “strong worldwide demand for safe assets” with a true economic boom – unless you have to.

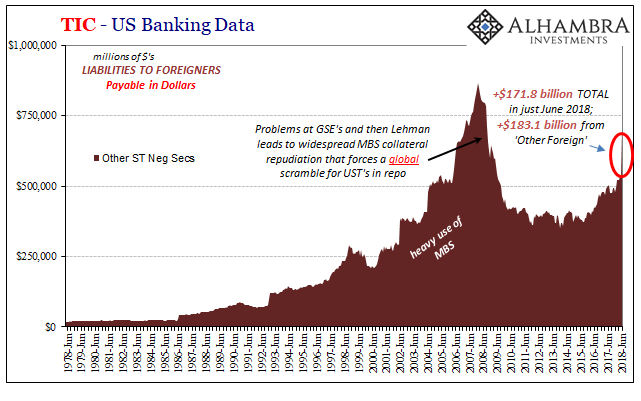

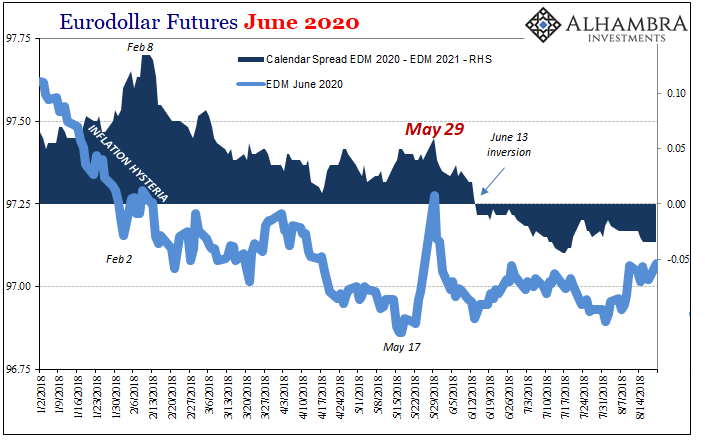

Why now? Why the inclusion of this particularly absurd passage? In my view it simply has to do with May 29. That’s the whole “strong worldwide demand for safe assets.” The FOMC is perfectly free, of course, to speculate wildly and irrationally in order to dismiss the ramifications in terms of a(nother) global “dollar” disruption and the myriad deflationary signals multiplying and broadening, but that’s a luxury the world just doesn’t have.

It is, in fact, the whole reason the yield curve just won’t get with the FOMC on anything. They continually rationalize for what is really simple so as to reverse engineer a conclusion that markets won’t (can’t) reach. That starts with the fact that the money system isn’t operating at all in the way it does in the official fairy tale.

Because it is that simple, there can only be these absurd detours. The FOMC statement is pure entertainment.

Stay In Touch