The competition was fierce. Vying for the eventual affections of Indonesia’s traveling public, Japan and China were locked into an auction of one-upmanship. Businesses from both countries had submitted bids to build the first high speed rail line in the growing emerging market center. As a first step, there would be bullet train service between Jakarta and Bandung.

Ultra-fast trains are the primary selling point behind getting onboard China’s One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative. In 2015, while the Chinese were wooing Jakarta’s politicians, Premier Li Keqiang was showing off the technology for European leaders. Taking them on a demonstration ride between Suzhou and Shanghai, Li predicted that what he saw as China’s railway edge would become OBOR’s “golden business card.”

Later that same year, Xu Shaoshi, China’s Minister of the National Development and Reform Commission, after meeting with Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo told the international press, “our proposal is better. We promise we can deliver this project in three years starting with groundbreaking in August…and it will be completed in 2018.”

Jokowi, as Indonesia’s leader is known, would deliver the bad news to the Japanese delegation shortly thereafter. His government had picked the Chinese as “partners.”

A groundbreaking ceremony was staged in January 2016. More than two years later, not a single mile of track had been laid. One media report suggested only about 100 meters of one of the tunnels required for only one of the four stations along the route had been dug. There were allegations it would take another two to three years just to finish the tunnel.

The Jakarta-Bandung railway project was supposed to be a crown jewel – for both countries. The Chinese have been desperately eager to show off the promises of OBOR, the benefits of participation. Jokowi knew he was going into a political fight and wanted a shiny new success story as a clear example to sell his re-election in April 2019.

Indonesia’s opposition instead seized upon it and how China’s massive investment was starting to be perceived by the Indonesian public. Rising political star and VP running mate for Prabowo Subianto, the man challenging Jokowi, Sandiaga Uno promised repeatedly on the campaign trail to undertake careful review if not cancel Jakarta-Bandung entirely.

Not only is the project way behind with budgets exploding, there are the terms of the agreement itself.

If it creates jobs for Indonesians, not for Chinese, I would [accept Chinese investment]. When I did inspections…even the coke came from China. I would still invite them, but at terms beneficial for Indonesians’ jobs and with good quality.

Rumors had already spread on social media that 11 million Chinese workers had been imported along with material. Resentment runs high in Indonesia, relations with China strained by Communist interference in the sixties and the bloody backlash it provoked. Indonesians don’t necessarily trust the Chinese, and OBOR’s initial re-introduction certainly has not helped.

Jokowi would ultimately win the April election, but the vote tally was much closer than anyone anticipated. And, as has become more frequent in our current recovery-less economic climate, Prabowo Subianto has not conceded vowing to contest the result. The official tally is not yet known, but polling indications which have proved reliable in the past suggest Jokowi’s victory.

Subianto has offered to relocate the same pollsters to Antarctica so that they can “lie to the penguins.” Economic growth seems so hard and contentious to accomplish in the 2010’s.

Jakarta-Bandung may continue onward, though the re-elected President has become more sensitive to opposition questions about it. And China’s involvement.

In 2017, the Financial Times investigated three high speed rail projects associated with OBOR. The paper said that 18 such schemes had been announced by that year, one completed, amounting to a staggering $143 billion in total “investments.” However, several had already been canceled.

In Venezuela, late Socialist dictator Hugo Chavez bragged about the future of Chinese money in the country, predicting “socialism on rails.” He was right, ultimately, though not in the way he was feeling it. Locals have lamented this foolish “red elephant” which wasted so much money not to mention opportunity.

One Chinese official in the National Development and Reform Commission expressed unease with the driving force behind what would become OBOR.

China had no choice but to lend a lot to risky countries because they had the commodities we needed and because the western multilateral organisations already dominated the rest of the world. These days we need viable projects and a good return. We don’t want to back losers.

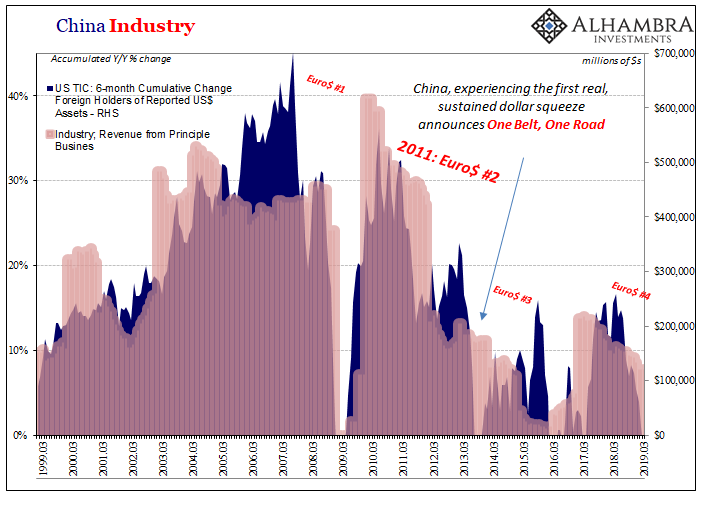

The common link behind a lot of the financing ends of all these projects is the global currency lacking for them. The Chinese give them what dollars they must while at the same time opening the door for yuan. If you understand how it has become harder for China to obtain dollars, OBOR makes perfect sense.

Indonesia’s Jakarta-Bandung project was financed mostly by loans from China Development Bank, though questions remain about exactly who gave the order. Sixty percent of the $5.3 billion funding is denominated in US dollars, the remaining 40% in yuan. Give the target the most concessions, and give up some precious dollars to do it, but extract in return the future; payment for resources in yuan.

To many, it has started to look more like an extortion racket. You need the dollars; we get to tell you how things go once you inevitably fall behind on payments.

The FT’s investigations, which covered Indonesia as well as others in Laos and Serbia to Hungary, found the primary sticking point to be just that.

The first issue surrounds the vastly divergent capacities to take on and absorb debt. China’s economic heft and authoritarian system allows companies that enjoy effective government guarantees to load up on loans and operate at a perennial loss.

China’s banks aren’t looking to make much money from their involvement at all. Their motivations are transparently different. In fact, as noted above, they’ve been directed to lend out hundreds of billions to the riskiest borrowers on the planet. It makes you wonder, why the clear coercion? What’s their hurry?

The world is waking up to the possibilities and beginning to ask just those kinds of questions. Indonesia’s neighbor Malaysia after 2018 elections that did go the way of the opposition party announced the cancellation of two huge Chinese-backed projects. Totaling a massive $22 billion, these were major OBOR setbacks, as The New York Times reported last summer:

But where Malaysia once led the pack in courting Chinese investment, it is now on the front edge of a new phenomenon: a pushback against Beijing as nations fear becoming overly indebted for projects that are neither viable nor necessary — except in their strategic value to China or use in propping up friendly strongmen.

Give us something we don’t need nor really want and then extract the most favorable terms as concessions? Like shifting from dollars to yuan? This would include, presumably, one-way payments for raw materials that would reduce China’s dollar footprint. The oil countries of Africa can already attest.

An extortion scheme seems hardly the way to de-dollarize the world. Then again, do the Chinese have another, better option? It might be down to the least worst. They can’t negotiate any other kind of payment or reserve currency scheme because in the West officials can only say the global economy is booming – never mind the most recent “soft patch” falling hard on China.

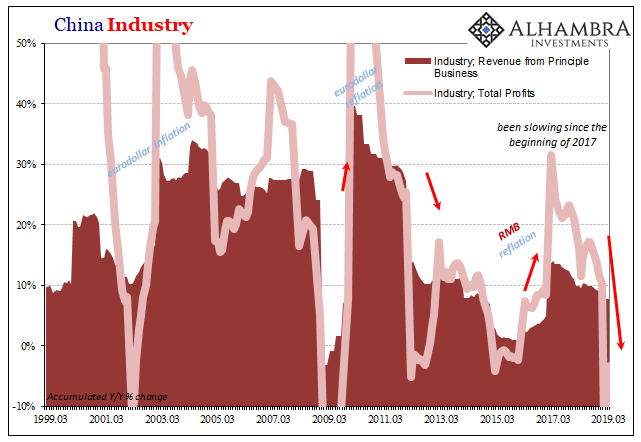

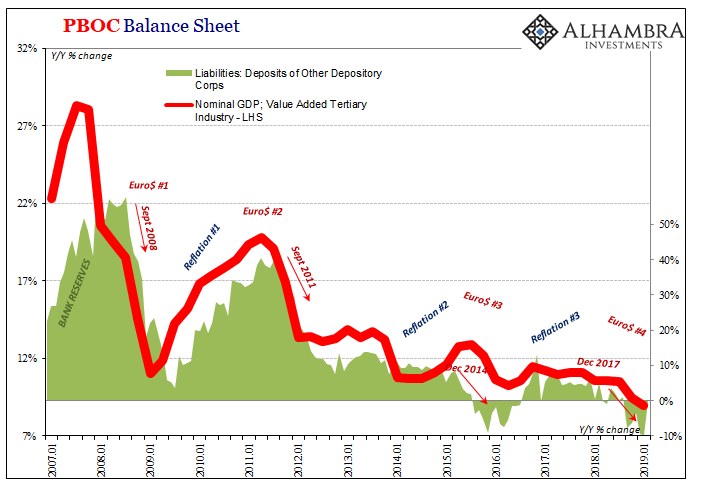

The timing makes perfect sense. The downturn in 2015-16, Euro$ #3, hit the Chinese and EM’s very hard. The political maneuvers inside the country suggested officials knew very well globally synchronized growth was going to end badly. At least nothing like globally synchronized growth. The pressures internally were still building, not abating.

Chinese banks were told no country was off limits no matter how unsavory its profile, no project too extravagant, no risk was too big. OBOR must move forward in the biggest way possible. Get it done quickly, no matter how much must be overpromised at the start.

The clock has been ticking.

Back in October 2015, after being informed Jokowi was going with China for Jakarta-Bandung, Yoshihide Suga, Japan’s Chief Cabinet Secretary under Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, was stunned and more than a little skeptical.

It defies common wisdom [to undertake such a massive project financed by foreign money]. I doubt if it would be successful.

It seems as if he wasn’t speaking from sour grapes. Though Suga was talking about losing the railway project to China’s big bank concessions, might he have been speaking more broadly about OBOR?

The Chinese are now quite interested in hearing complaints. Xi Jinping’s most recent speech on his country’s ambitious program was conspicuously different than those of the past, even made recently. Perhaps Xi is trying to gain favor in negotiations with the Trump Administration over “trade wars.” More likely, though, the Chinese were in such a rush they simply pushed it too far, too fast.

Mr. Xi invited foreign and private-sector partners to contribute more funding, a contrast to his pledges of Chinese financing in a similar speech two years ago.

Beijing is fine-tuning Belt and Road, according to Zhang Zhexin, an analyst at Shanghai Institutes for International Studies. Its initial presentation was too broad and too loud, he said, and participating countries—often in distress—saw the program as a source of easy money from China.

When the most loyal customers of any payday lender start saying no to new “easy money” the jig is up. De-dollarization is going to have to come about some other way. If that’s possible.

The clock, however, is still ticking. Not only is China’s economy getting worse, Chinese banks are now bloated with debt undertaken for reasons that have little or nothing to do with prudent lending. Rather than help ween the country’s system off “dollars”, this first phase of OBOR just might’ve made it all worse.

For having turned prospective opportunistic partners into suspicious if not hostile neighbors, China’s economy gained no discernible benefits and increased the risk of its most outward-facing banks. In other words, the risks of more rapid and unplanned de-dollarization have been hugely amplified. A run, if you will.

Xi’s softened tone makes more sense in that context. The real trade wars are being waged in the shadows.

Stay In Touch