JP Morgan’s CEO Jamie Dimon has been running around Washington claiming that mid-September’s repo rumble was the result of the post-crisis regulatory environment. He now says that his bank had the spare cash and was willing to cash in on double digit repo rates but it was government rules which prevented that from happening. It’s unclear (but we can, and I will, guess) why he didn’t make the same claim and warn everyone on Friday, September 13, before the seasonal low point in liquidity that everyone knew was there.

It wasn’t until quite a while afterward during that period when a stunned financial world was still trying (and failing) to make sense of what had happened.

You probably won’t be surprised to learn that this isn’t the first time Wall Street has complained about these very same regulations. They’ve been against them from the very beginning. What’s different now is that they have a very public event about which nobody has any real answers to rally support. It all sounds pretty plausible (it always sounds plausible).

Suddenly, Treasury Secretary Mnuchin seems to be siding with the banks. Having spoken directly with Mr. Dimon recently, Secretary Mnuchin today says:

The banks have raised an issue around intra-day liquidity, and that is something that makes sense for regulators to look at.

That issue they’ve raised is something called the Supplemental Leverage Ratio, or SLR. It was created and applied to Global Systemically Important Bank organizations, or G-SIB. The FDIC, in particular, had pushed for the SLR because quite rightly the agency wasn’t very thrilled about the prospects for having to absorb potential deposit liabilities of huge banks sporting enormous leverage getting shut out of wholesale funding markets.

The Global Financial Crisis of 2008 demonstrated conclusively this wasn’t a trivial possibility.

To put it very simply, regulators would require designated G-SIB’s (there are 8 in the US) to hold an additional liquidity buffer (SLR) based upon their reported leverage (one lesson authorities did learn from Bear, Lehman, and the rest). It would be a liquidity surcharge which would have to be met by a set percentage of holdings in unencumbered cash and highly liquid assets like UST’s over and above other regulatory and good standing requirements.

If any G-SIB bank wanted to employ more leverage, more power to them. The regulation was an attempt to recognize partly the risks to others beyond the one bank involved in doing so. Regardless of capital ratios, worthless capital ratios, beyond a preset threshold the more leverage the greater the SLR; more liquid assets including cash and Treasuries need to be held as further liquidity reserves.

So, again, blaming the SLR sounds like a plausible excuse for September’s repo malfunction. JP Morgan, as its CEO now says, wanted to act but couldn’t because his bank’s SLR surcharge was the primary impediment.

We also know this because they said essentially the same thing in September…2018. Again, you probably won’t be surprised to learn that early on last year the banks were supporting regulatory efforts to make changes to what is now the e-SLR (the “e” stands for “enhanced” while there is room for debate about whether that’s the proper use of that particular word in this context). Martin J. Gruenberg, an FDIC board member, spoke in Washington last September to that effect:

On April 11 of this year [2018], the Federal Reserve Board and the OCC released a joint notice of proposed rulemaking, or NPR, to make changes to the enhanced supplementary leverage ratio capital requirement applied to the eight U.S. G-SIBs and their federally insured bank subsidiaries. The changes would have the effect of reducing the capital requirement. They are not technical fixes. They would significantly weaken constraints on financial leverage in systemically important banks put in place in response to the crisis.

And where did that “e” come from in the first place? Way back in July 2017, Wall Street was lobbying for changes to the same regulatory paradigm back then, too. What I wrote at the time was:

Released on June 12 [2017], it suggested that the SLR might be reformulated to make it less imposing. The SLR was initially proposed so that the risk-weighting shenanigans (regulatory capital relief) would at least be exposed by this measure of true(r) leverage. It takes Tier 1 capital divided by the sum of on-balance sheet assets plus off-balance sheet exposures. There is still a large gray area in that latter variable.

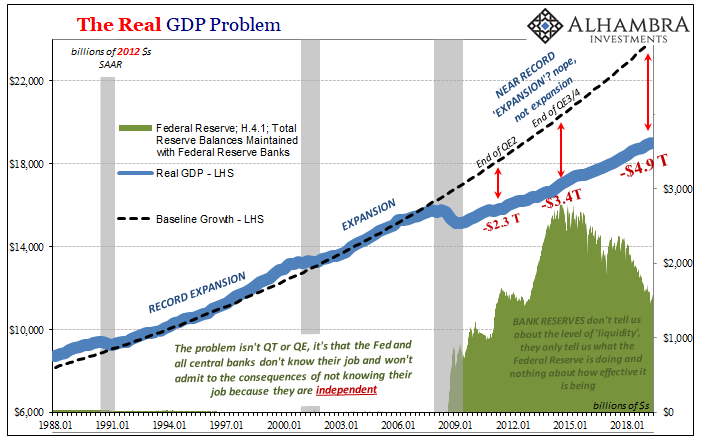

Banks want now to deduct certain cash and liquid assets (including UST’s) from it. The result of which is supposed to, in Treasury’s estimation, unlock significant liquidity potential of the global banking system from just American operations. It is, in other words, the official acceptance of at least part of the idea that one big problem in the economy is insufficient liquidity (no sh@#).

The banks succeeded and Secretary Mnuchin’s Treasury Department issued its favorable report that very June. Most attention was focused on what it said about the so-called Volcker Rule while the more complex (and more relevant) SLR, e-SLR, and G-SIB designations remained in the shadows.

To sum up: Wall Street has hated almost every single post-crisis regulation that has been implemented, though in some cases they’ve been right to do so. However, there is absolutely no reason to believe that the e-SLR or G-SIB rules had anything to do with the repo market outbreak in September 2019.

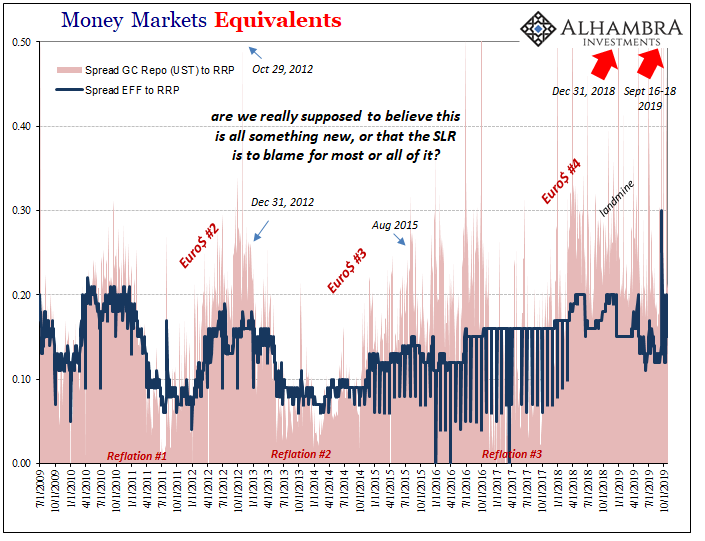

What’s been constant is the banking system’s ongoing efforts to remove these kinds of regulations. At the same time, problems in the repo market have been nearly as constant. Yet , you didn’t hear a single thing about the SLR during any of the other outbreaks simply because no one paid any attention to those prior bouts of repo market illiquidity.

There was no opportunity, therefore, to pin the regulation on something bad.

The only thing that changed, in its aftermath, was that the public for once had no choice but to look at the repo market and the funding environment. With attention now fixed and no plausible answers being offered, all of a sudden it’s now evidence against a regulation banks have been actively opposing for years.

Shocking, I know.

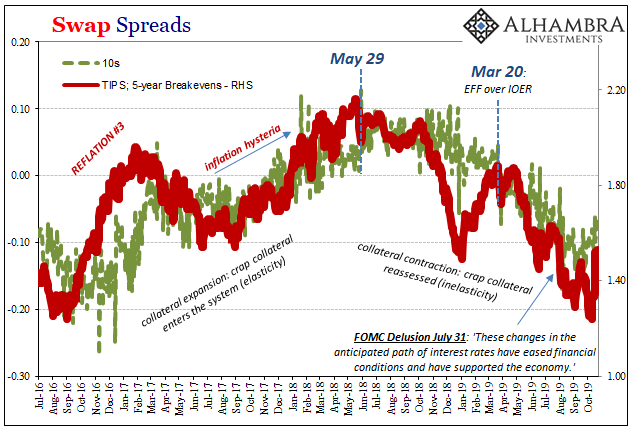

As is the fact that May 29, 2018, had more to do with these repo market woes than anything about the SLR and the like. If that particular constraint was such a major issue in September, why wasn’t it in May 29 the prior year when the Treasury market began to embarrass Mr. Dimon and his prediction of 4% and even 5% 10-year UST yields? Repo rates were elevated at that time, too.

Obviously, in the middle of 2018, the head of JP Morgan, the bank allegedly suffering under the unfair imposition of out-of-touch regulators, saw no reason why the US and global economy wouldn’t soar in an all-but-guaranteed inflationary breakout (interest rates had nowhere to go but up). Implicit in that view was a resilient and robust global financial system flourishing without the hint of liquidity issues.

Dimon opposed the SLR when he fully believed things were really good, and he opposed the SLR now that he’s not so sure and he has something bad to show. And he will oppose the SLR tomorrow whether things really turn around or not.

So, is it that Dimon had no idea what was really going on during 2018 at his own bank, and has therefore come around to thinking some version of the SLR is to blame for getting 2019 all wrong? Or, is it because he had and has no real idea of the liquidity system that after being caught totally off-guard by pretty much everything he is cynically seeking to settle a longstanding score about the one thing he does know well?

When I came up with the zoo analogy to try to describe what’s going on, I didn’t realize just how well it would fit the times. What’s worse, the financial media will now be filled with stories about how it must be that Dimon is right! A real zoo. And nothing will change, even if the SLR does.

Stay In Touch