They staked everything on inflation. In truth, central bankers had no other choice. Having backed themselves into such a narrow corner by doing the same thing over and over and over again, it was only going to be one or the other. Either it worked or for all time they would prove they really have no idea what they were doing.

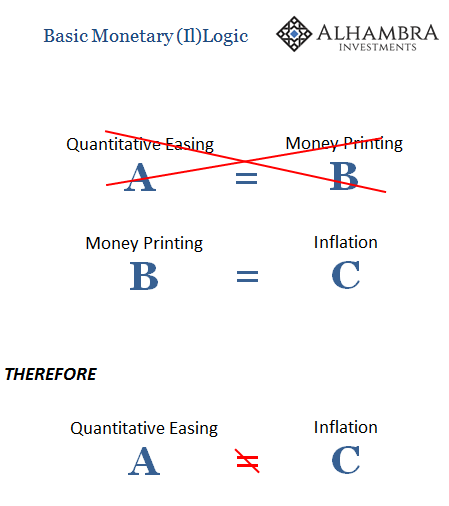

The proof would be inflation, that mysterious combination between money and prices. Only, it isn’t really all that big of a mystery. Economists may not know how one becomes the other, but that doesn’t mean we can’t unpack the conditions whereby it is likely, or unlikely, to happen.

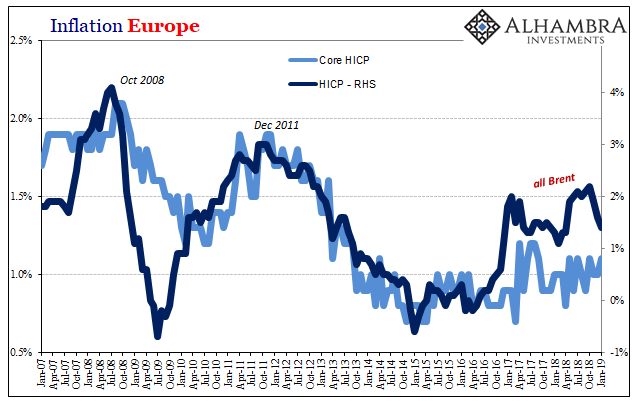

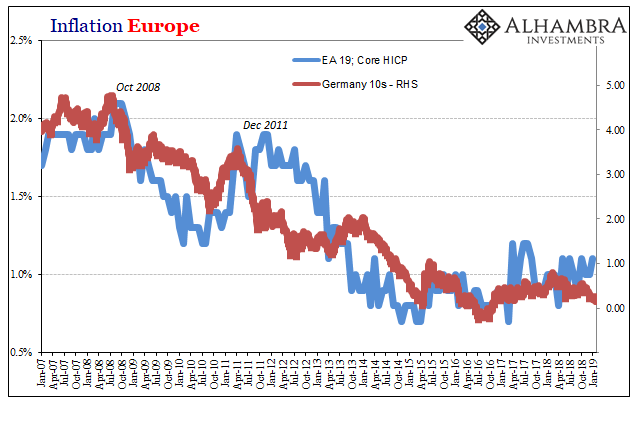

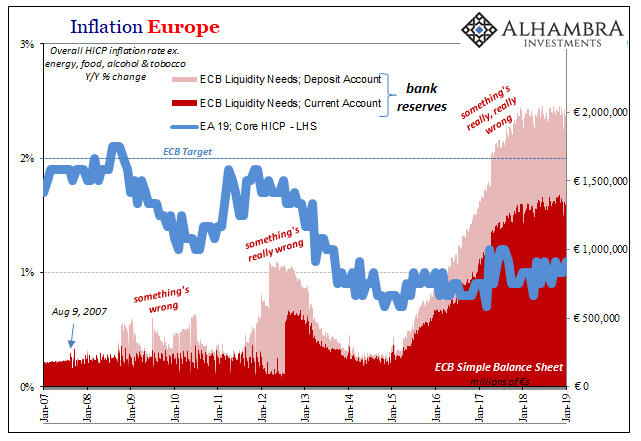

In Europe, for Draghi’s boom to have had any chance, we would see it in the Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP). But it never actually showed up; the evidence the ECB was looking for was always future tense. Even with a double dose of Brent oil prices, the index never really got that much above the 2% target.

If you can’t break 2.2% with a massive oil price tailwind, something isn’t right.

This really wasn’t a surprise, though you might not have known it reading media reports and mainstream commentary. Amidst last year’s hysteria, in January 2018 Mario Draghi uncorked a whopper:

The strong cyclical momentum, the ongoing reduction of economic slack and increasing capacity utilisation strengthen further our confidence that inflation will converge towards our inflation aim of below, but close to, 2%. At the same time, domestic price pressures remain muted overall and have yet to show convincing signs of a sustained upward trend. [emphasis added]

It is the true talent of any central banker at the top of his game, being able to contradict yourself in the space of two sentences without pause. As per usual, not a single member of the media has ever asked him to clarify his two stated positions directly at odds with each other.

While that would’ve been helpful, we don’t really need them to. We have other tools at our disposal to more appropriately, and honestly, evaluate the situation. Even during the last part of 2017 and the first part of 2018, there wasn’t much to suggest “strong cyclical momentum” or anything else to believe in recovery and its inflation. There was no boom except in Draghi’s publicly conflicted mind.

As that realization dawned during the last few months of last year, another far more realistic scenario was queued up. Not only was the global economy failing to accelerate, it was taking on more and more downside positions. Markets were askew and data on the economy shifted. Sour, not soar.

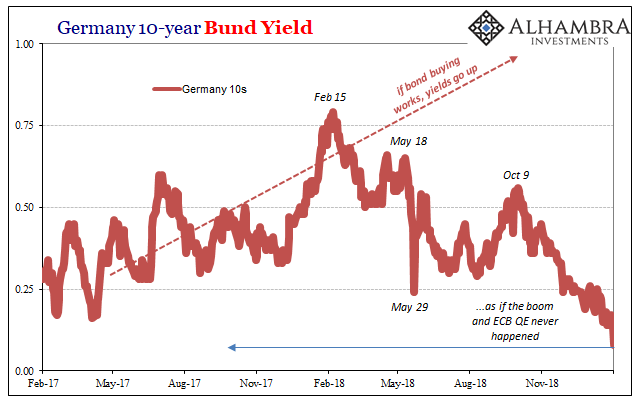

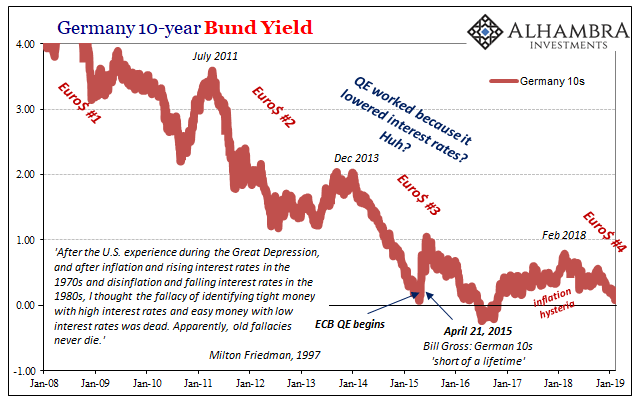

How bad has it gotten? As of today’s European close, Germany’s 10’s are yielding all of 8 bps (JGB 10’s now -4 bps, for corroboration). That’s the lowest yield for this global benchmark since October 2016. Reflation #3, what little there was of it, has been completely erased.

As I wrote yesterday with regard to falling LIBOR, big things are happening right now; they’re just all negative.

The most frustrating aspect, beyond the simple tragedy of another looming downturn which for Europe looks like possibly a nasty recession, is that these bond prices have said all along what’s keeping the economy down. Inflation and recovery never had a chance.

Over the past few years, Europe’s central bank under Draghi has been lauded for its courageous action. The ECB’s policies were celebrated especially in 2017 as if having already achieved visible success, but based solely on the ECB’s self-assessments.

The numbers are absolutely staggering, and therefore leave us absolutely no doubt as to the failure. As of yesterday, Europe’s central bank in conjunction with the various constituent national central banks has bought €2.54 trillion in securities (only counting the three major programs: PSPP, or QE, €2.10 trillion; covered bonds €262 billion; corporate bonds €178 billion).

The byproduct of those purchases has been the creation of just over €2 trillion in bank reserves (not counting the effect of autonomous factors due to the NCB involvement in PSPP). There’s €1.36 trillion of them sitting in the current account yielding nothing, and €657 billion in its deposit account costing banks 40 bps to hold them.

How do you end up with German 10s at 8bps and inflation falling after all that massive “stimulus?”

The answer is very simple. Central banks don’t do money. They just don’t. It never was stimulus.

Milton Friedman correctly observed in 1997 that persistently low rates are tight money in the real economy. If Europe’s bond market rates have remained low despite more than €2 trillion in “money printing” ipso facto it isn’t money printing. Instead all the ECB buying has been a distraction, its true purpose, by the way, ultimately a harmful one because it wasted so much time that could’ve been better put to use solving the world’s persisting money problem.

That’s what Germany, Japan, the US, etc., all these bond markets are saying – and have been for more than a decade. The monetary system is wrong and broken, and all central bankers do is wave their magic wands for the entertainment of their captured audience (the entire mainstream media). Booms are not possible under these circumstances.

With inflation falling again, core rates having never risen at all, there isn’t even the promise of “our confidence that inflation will converge towards our inflation aim” any longer. Falling yields mean rising liquidity preferences because of rising perceived liquidity risks. If money was tight throughout the last reflation experience, when things were supposedly good, then what might it mean with even more private market tightening easily observable right now?

Euro$ #4. It’s shaping up to be one of the nastier versions. With Germany’s 10s just a little above zero again, not only is it nothing good now it also means Europe’s just getting started. And like 2011, this isn’t just about Europe.

Stay In Touch