The Volcker Myth is simple because there isn’t math for it just voodoo economics (to borrow George HW Bush’s phrase). In theory, the FOMC finally realized after more than a decade of currency devastation and its economic, financial, and social consequences, hey, inflation and money.

Once Paul Volcker took over in ’79, he acted on the belated realization, seeking to get the Great Inflation under control by restricting, well, something that seems like money.

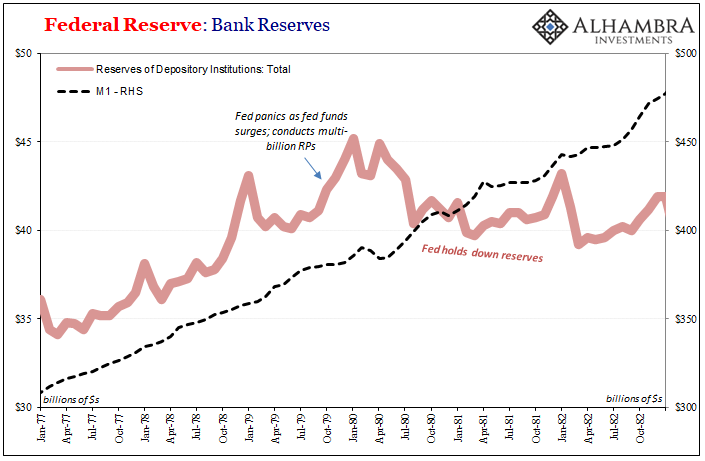

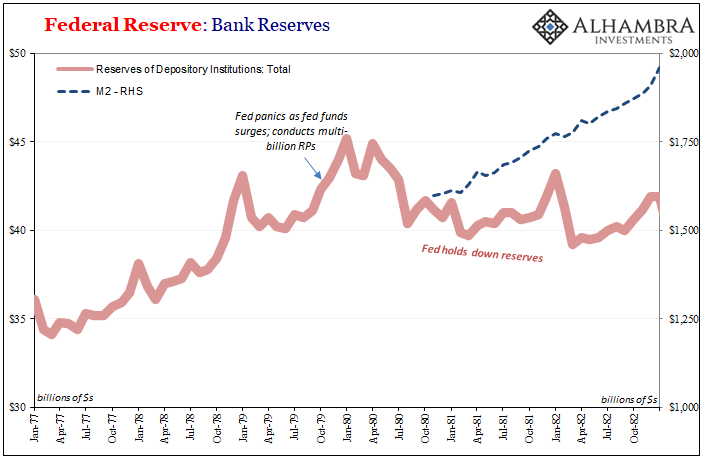

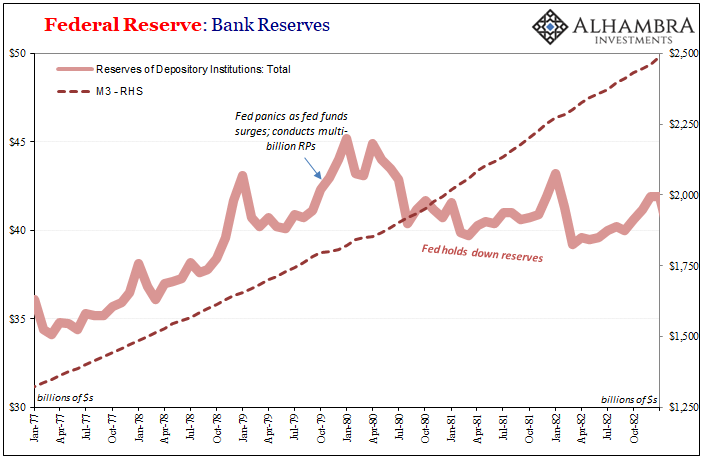

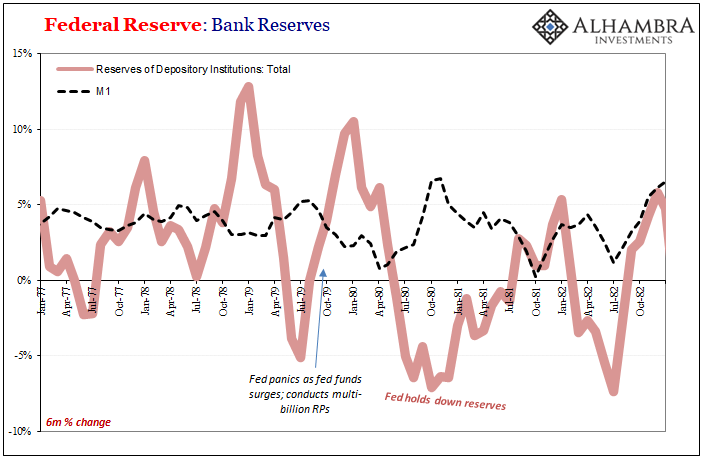

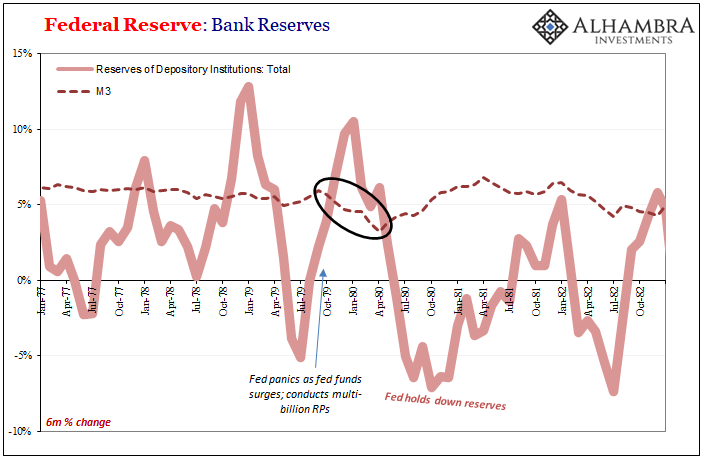

All the Fed had by that point was bank reserves, so they gave it a go. Late in 1979, authorities restricted bank reserves with kind of an expectation, more like pure hope more costly reserves would constrict depository money. And if they did, that would limit bank credit and then money flowing into the real economy thereby choking off inflation.

Volcker Myth in its most basic form sounded good: restrict bank reserves thereby undercutting depository money which would constrain bank credit therefore get a handle on inflation.

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_AIP) June 4, 2022

Fed stumbled on the first part in '79, by '81 kept pressure on reserves.https://t.co/3UjkO31dzq pic.twitter.com/SsiplSsUZy

As discussed in detail previously, Volcker’s crew didn’t start out well at all. The FOMC, in fact, panicked almost immediately when the fed funds rate jumped (what were they expecting?) Either way, once officials got comfortable with effective fed funds at whichever level, it didn’t matter anyway.

In fact, none of it made a difference; there was never a correlation between bank reserves and money of any stripe. Even using the by-then long outdated Ms, even M3, you can clearly see that, nope, bank reserves and money growth had no relationship whatsoever.

The dip in M3 late in ’79 (circled below) is actually a contrary move, too, because M3 growth slowed right when the FOMC was adding back more reserves via RPs during its fed funds panic. And then once they went forward reducing reserves, M3 then accelerated.

https://twitter.com/JeffSnider_AIP/status/1533193876453961728

You just can’t make bank reserves into any kind of monetary relationship because bank reserves are not money; at best, a token with limited use and purpose. The monetary system had expanded for decades by then both qualitatively as well as quantitatively, and what that had meant was banks did all kinds of things which neither had use for bank reserves (at any cost) nor which the Fed could figure.

So, years after this period, the gaslighters in Economics decided that it hadn’t been bank reserves, per se, which caused the early 80s recessions and an end to the Great Inflation, rather it must have been the accidental impact of rising (real) interest rates holding back bank reserves had caused.

By constraining them and driving up the fed funds rate, rates were suddenly thought the magic cure. From that point (the gaslighting) on, the exclusive emphasis on interest rates, particularly fed funds, rather than money and any kind of aggregates. The narrative shifted to the ephemera of interest rate targeting because money, well, that ship sailed in the sixties and everyone inside the Fed knew it.

What else were they going to do? Honestly examine the eurodollar? Tell the public?

This wasn’t strictly an America or even dollar evolution. Banking and money in more general terms, a fact we can observe both in the Volcker Myth as well as its opposite end.

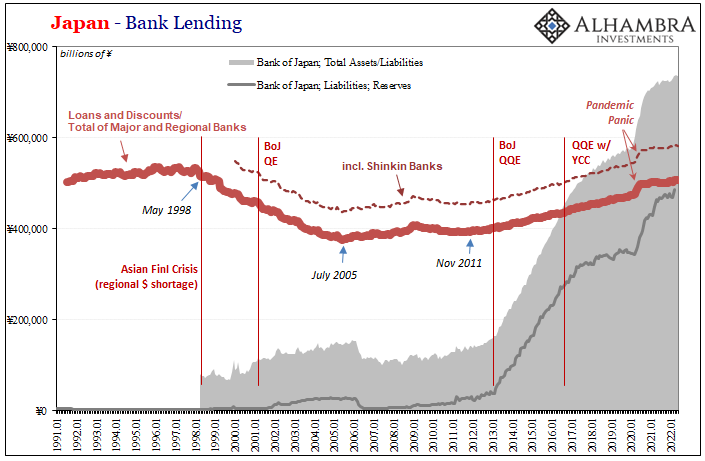

What’s the opposite of early eighties FOMC bank reserve restraint? Twenty-first century Japanese QE which massively expands the level of same.

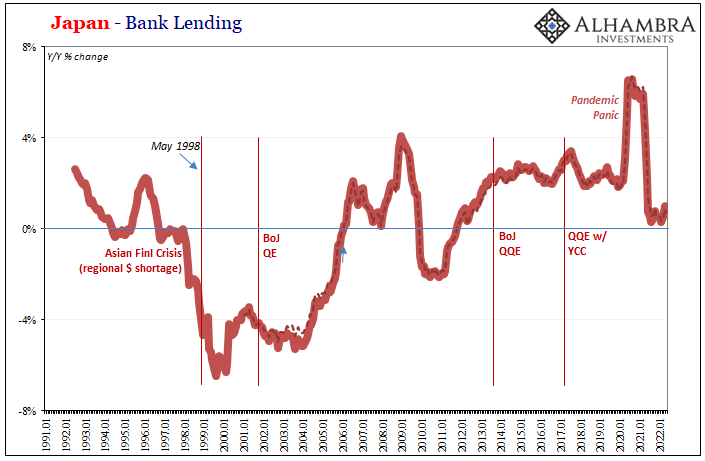

No need to belabor this point too much, but, like Volcker’s mess, in Japan over the past two decades once again we see no correlation whatsoever between bank reserves and at least credit growth (I didn’t have time to produce the yen Ms here, but they show the same).

Early in the QE era, bank reserves rapidly expand yet credit continued to decline for years therefore economy stuck in deflation never coming close to liftoff. Same for post-2008 and again post-2020. Credit growth in Japan right now is ridiculously low again, regardless of the Bank of Japan’s absurd theater.

As Emil Kalinowski reminds us, it’s just past the anniversary of Haruhiko Kuroda’s bizarre yet appropriate Peter Pan confession.

I trust that many of you are familiar with the story of Peter Pan, in which it says, ‘The moment you doubt whether you can fly, you cease forever to be able to do it.’ Yes, what we need is a positive attitude and conviction.

In other words, ever since the Volcker Myth, bank reserves aren’t actually money but if you believe they are the whole economy can fly.

No joke, they truly think this is what happens. That’s the myth; there’s no money in “monetary policy.”

Uh, yeah. That's the f-ing problem, assh—. https://t.co/e9wTyVJfS2

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_AIP) May 26, 2022

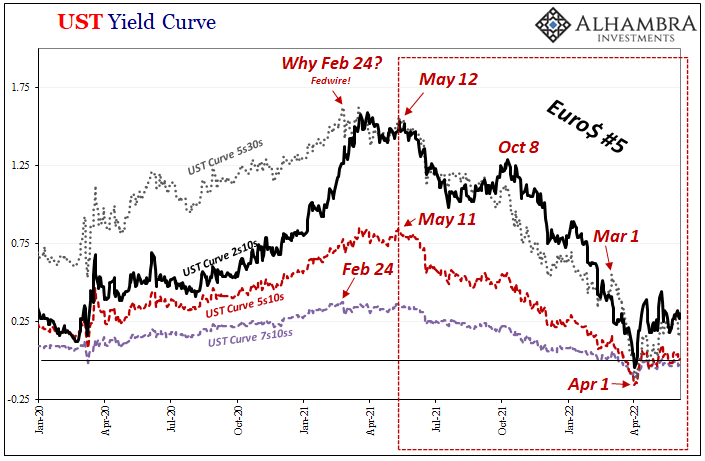

The implications are more serious than critiquing some fairy tale, obviously, including, as noted yesterday, the equally ridiculous notion the World Bank has put forward for its growing (very real) recession unease. Blaming rising global contraction risks on 70s-style inflation, that’s only because these Economists are Peter Pan fans rather than honest and detached scientific observers of money and economic reality.

Inflation, they do know, isn’t actual money printing because bank reserves aren’t money, rather “monetary” policy has been deemed “highly accommodative” because Economists believe a lot of people around the world have believed a la Peter F-ing Pan.

You might think I’m just making all this up, and I absolutely understand why you’d think so; it really is just so preposterous. Unfortunately, unlike Kuroda and Volcker, I don’t have to make believe.

Why this matters, risks of recession, yes, but of a different sort (including what comes after) than 70s style.

Stay In Touch