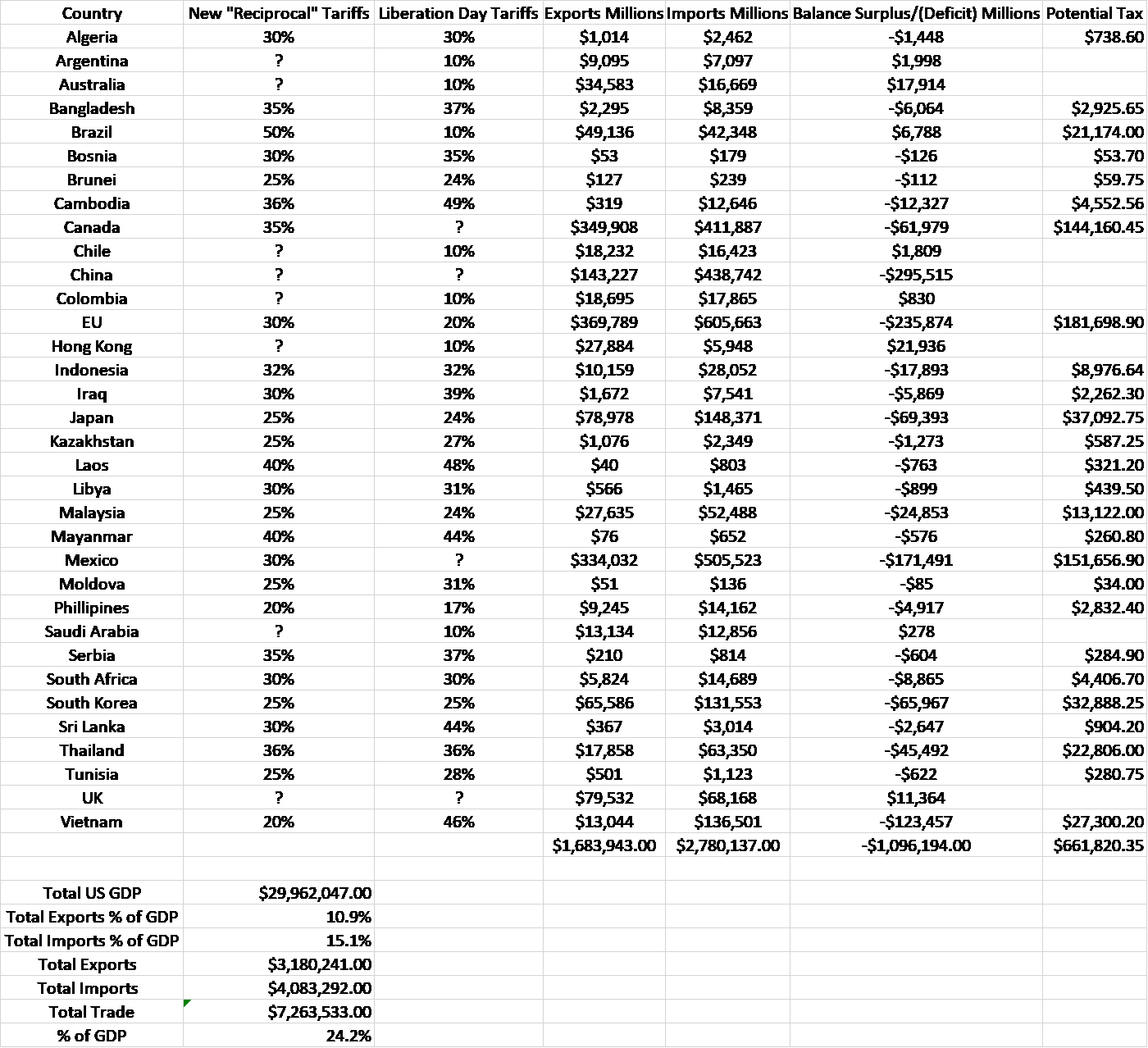

Last week President Trump announced, via a letter posted on his social media site, that products from Brazil would face a 50% tariff, starting August 1st, due to their treatment of former President Jair Bolsonaro, who is on trial for trying to overturn his 2022 election loss. The President also cited Brazil’s treatment of US social media companies, which the Brazilian Supreme Court recently ruled could be held liable for user-generated content, particularly content that promoted racism, hate speech, or incited violence. The Brazil tariffs were one of several announced last week, including Canada, Japan, South Korea, Philippines, Laos, Cambodia, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, and over the weekend, Mexico and the EU. Here’s a breakdown of what has been announced (this is not a comprehensive list and will probably be out of date by Monday and certainly by the new “deadline” of August 1st):

The first thing one notices about these tariffs is that they aren’t significantly different than the ones that caused a market meltdown the first week of April. The Mexico and EU tariffs were announced after the close Friday so we’ll have to wait for tomorrow to see how they affect markets but it doesn’t appear that the impact this time will be as great – at least initially – as the April 2nd announcement. There are at least two possibilities why they aren’t having the same impact as the first round. The first is summed up in the TACO acronym – Trump Always Chickens Out – which he seems determined to prove wrong. Will he finally follow through this time? Will August 1st be the end of this market melt up assistance device? I said on our podcast last week that by coining the term, Robert Armstrong may have ensured that the next round of tariffs will actually be implemented. So if the market melts down because Trump can’t stand being called a chicken, you can find Mr. Armstrong’s email address at the Financial Times website.

The other possibility is that investors and traders are assuming these tariffs are illegal and will be so ruled by the US courts. The “reciprocal” tariffs are being imposed under the IEEPA (International Economic Emergency Powers Act) which has never been used for that purpose. Certainly it is hard to see how the fate of Mr. Bolsonaro could possibly be an economic emergency for the United States. In short, it isn’t any of our business what the Brazilian Supreme Court does to its former presidents. The current president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Bolsonaro’s predecessor and successor, was charged with corruption and money laundering after his last term. He was sentenced to 12 years but was released early. One might see the current prosecution of Bolsonaro as retribution but whatever the truth, it isn’t an economic emergency for the US. It is hard to see how these tariffs stick if that is the only justification.

It is hard to see trade with most of the above countries as an economic emergency. If you take out the developed countries plus energy rich Brunei and Saudi Arabia, the average per capita GDP of the above list is just $7800/year. Bangladesh sending us cheap clothes is not an economic emergency. Cheap clothes and tea from Sri Lanka, luggage from Cambodia, coffee from Colombia, leather goods from Myanmar, fruit juice and plastic lids from Moldova, and olive oil from Tunisia seem hard to classify as economic emergencies. If anything, trade with most of these countries could more easily be classified as foreign aid rather than any kind of threat to the US economy. We aren’t going to balance our trade with these poor countries unless we just cut off trade with them completely. All that would accomplish would be to raise the price for whatever goods we import from them and further impoverish already desperately poor people. I suppose we could just say we aren’t interested in helping desperately poor countries unless they have something of equal value to offer in trade – which would mean they aren’t that poor – but that sure doesn’t sound like the America I know.

Of course, the President can find other justifications for imposing his tariffs, the most likely being the Section 301 tariffs which gives the President the power to impose tariffs on countries he deems to have engaged in unfair trade practices. There are, however, specific rules to follow when doing so which the current administration – and the last – don’t seem too concerned about adhering to. They would require, for instance, using WTO or specific trade agreement dispute resolution mechanisms. The other way the administration can impose tariffs is under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. This allows the President to impose tariffs on other countries based on national security concerns. The steel and aluminum tariffs as well as the recently announced copper tariffs fall into this category. If you look at the countries above though, it is hard to see most of them as a threat to national security. Indeed, even the industrial metals tariffs seem hard to justify on these grounds when most of our imports come from allies.

No one knows what will happen on August 1st, but I am certain that markets are not pricing in the full implementation of the tariffs announced so far. There has been a lot of discussion about the potential impact of these tariffs on prices (inflation) but not nearly as much on the effect on growth. The far right column in my chart above is Potential Tax which is nothing more than the dollar amount of imports from each country multiplied by the respective tariff rate. The total adds to over $660 billion but of course that number isn’t correct. Tariffs will affect imports and exports and the elasticity will be different for each country – and product for that matter. We also know that the incidence of the tax will be spread around. The exporter may agree to reduce his prices. The importer may pass along some of the cost to his customers. The importer may eat the costs and adjust in other ways, maybe by reducing his headcount or automating some process or by operating with a reduced profit margin.

We do know though that the importing companies will pay the tax directly – this is a tax increase on US corporations. Will it actually be $660 billion? No, but what if it is half that amount? The total tariffs collected in 2025 has already surpassed $110 billion and they obviously aren’t fully implemented yet. Treasury Secretary Bessent said last week that the US was “reaping the rewards” of the President’s tariff agenda – seemingly oblivious to the source of this bounty – and that the total take this year could grow to $300 billion. US corporate taxes last year were $530 billion so if we hit Bessent’s target, that would represent about a 56% increase in corporate level taxes. How much will an additional $300 billion in corporate taxes cost us in growth? There is no way to know in advance, especially when you have to also consider the impact of the recently passed budget bill. Will any positives from the budget bill offset the negatives of the tariffs? I have no idea but it seems unlikely that all the chaos of the last 6 months is going to be cost-free.

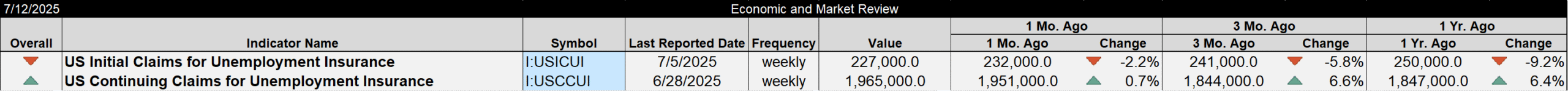

The impact on growth from the Trump administration’s policies also must include the impact of their immigration crackdown. Economic growth can be boiled down to just two factors: population or workforce growth + productivity growth. We may already be seeing the impact of immigration on the former in last month’s employment report; the foreign born labor force is down over 1 million just since March. That makes the latter factor – productivity growth – that much more important. I suppose forcing companies to pay higher costs may raise productivity eventually but it sure seems a painful way to do it.

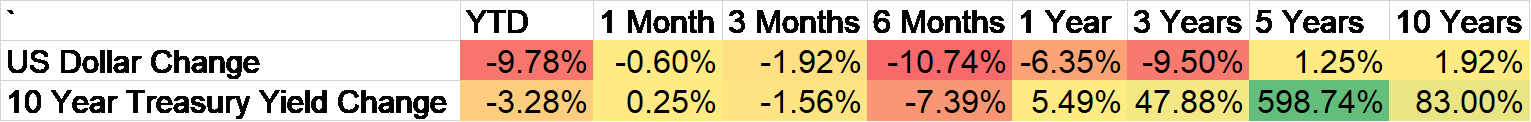

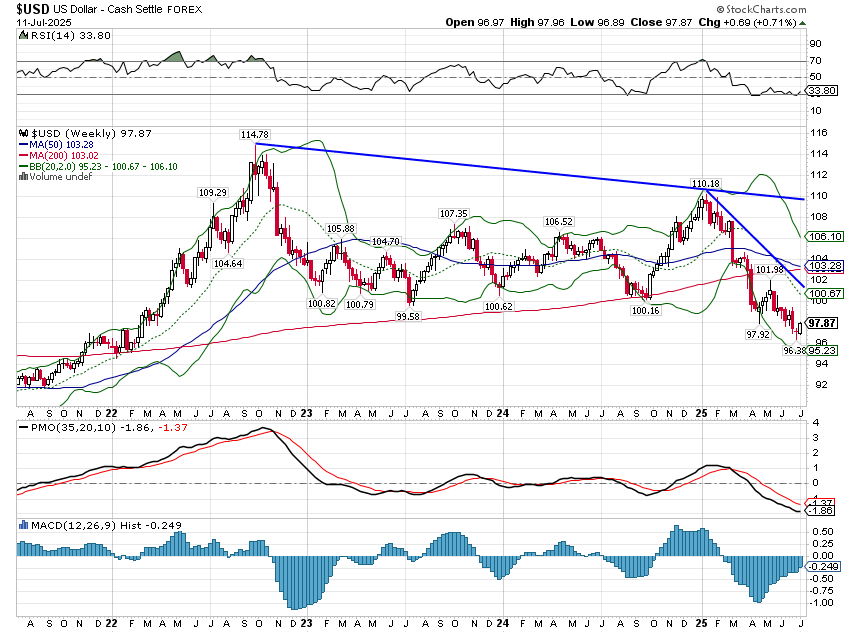

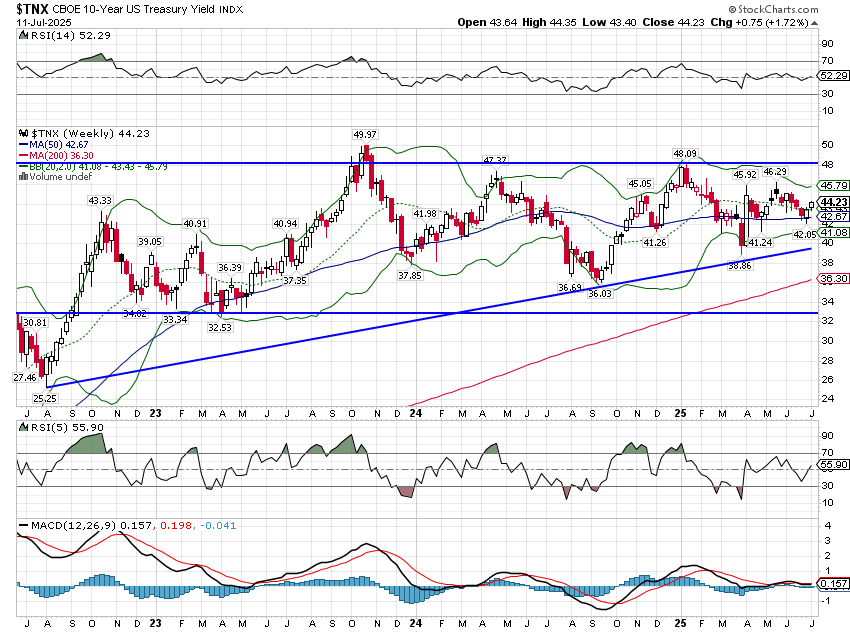

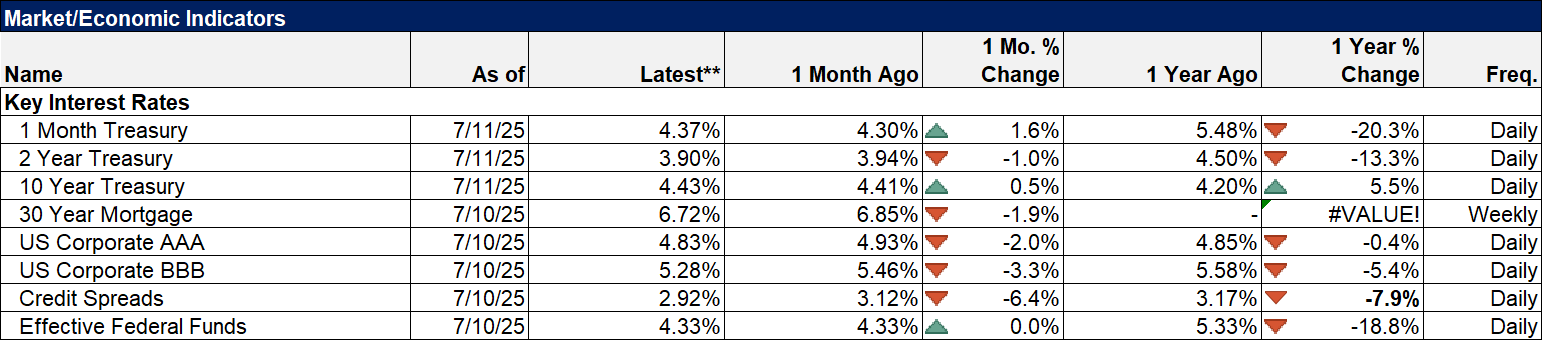

We know markets aren’t pricing in much change in growth from these policies because interest rates haven’t moved much. The 10-year Treasury note yield closed last week exactly where it closed the week of the election in November. 10-year TIPS yields have changed by only a few basis points. The only variable that has changed significantly is the value of the dollar which is down 5.6% since election day. That reflects, among several other variables, a positive change in growth expectations outside the US. Does it seem likely that the US could impose tariffs on the entire world and that the ex-US growth impact would be positive? How big an adjustment will markets have to make if TACO turns in to TAFT* (Trump Actually Followed Through)?

If and when all this Trump tariff chaos is over, maybe we ought to think very seriously, as a country, about the wisdom of granting one man – any one man – this much power over a quarter of our economy.

*My initial attempt at an acronym was TOFU, but this is a family publication.

Environment

The dollar rally I’ve been expecting may have started last week with the buck up about 0.7%. It will be very interesting to see the forex market reaction to the latest tariffs announced over the weekend. The dollar sold off on the Liberation day tariffs but that was a long time ago and the market’s view of these announcements has changed. The text book response would be for the dollar to rally as the US imposes tariffs so maybe we’ll see some further strength but even if we do I expect it to be temporary. Upside potential is to around 102 but that is probably too far. I’d be surprised if it can get much over 100.

The 10-year Treasury yield rose 7 basis points last week and remains in the upper half of its range of the last 3 years. It is amazing how steady bond yields have been considering all that is going on.

Markets

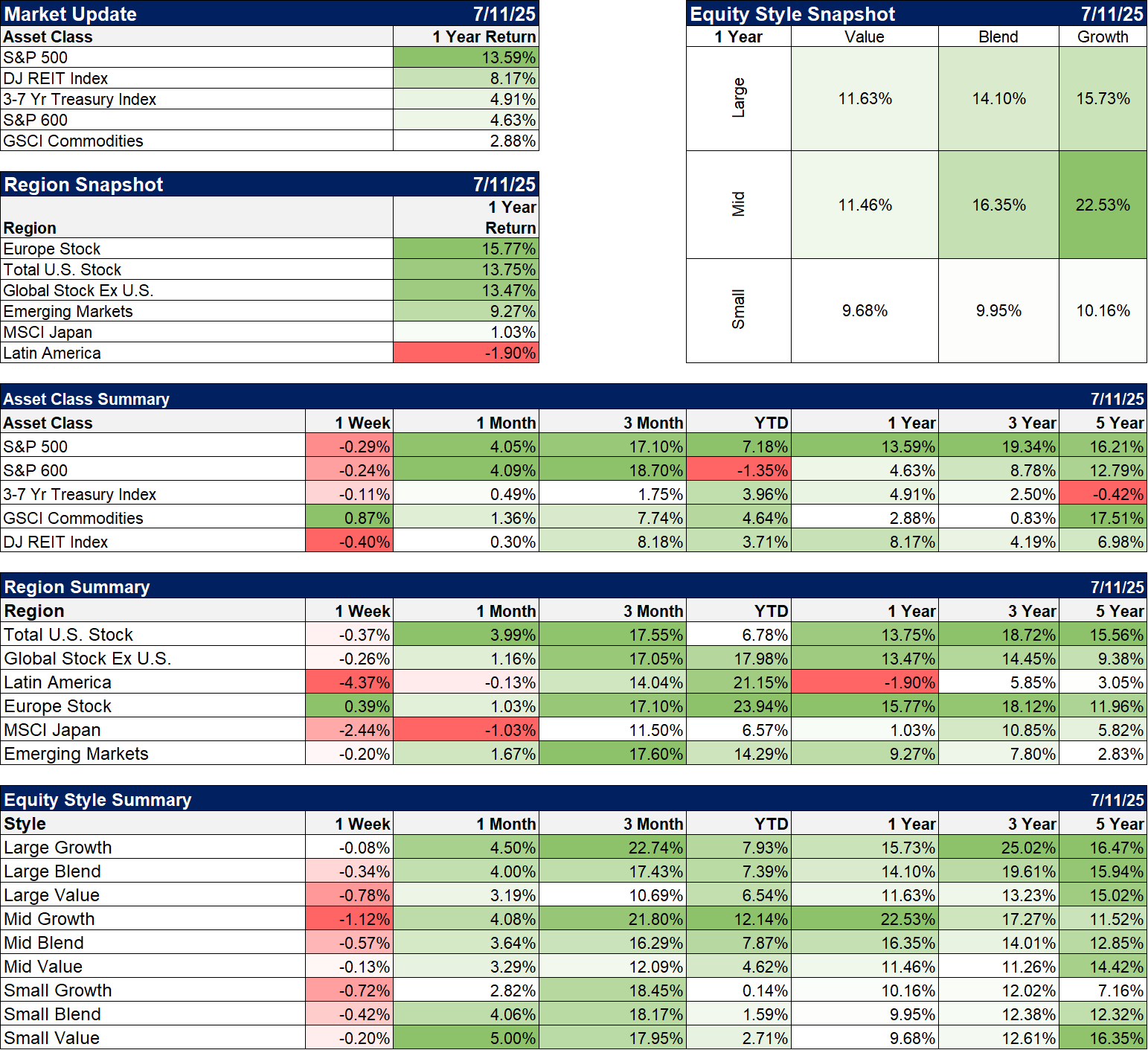

There has been a lot of talk about European stock outperformance this year but the trend actually started quite a while ago. If you look at only the countries that use the Euro, the outperformance goes back 3 years, with the EMU index outperforming the S&P 500 by about 15% total. Even more interesting and contrary to the consensus view at the time, this outperformance dates to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The thought at the time was that Europe would suffer badly because of their dependence on Russian natural gas. Conventional wisdom is rarely wise.

Another case of myopia is the value vs growth debate. I keep hearing how badly value has performed relative to growth but over the last 5 years, the only outperformance has been in large cap and even that is minor (16.5% vs 15.02%). Midcap and small cap value have both outperformed by much wider margins: Midcap 14.4% vs 11.5% and Small cap 16.4% vs 7.2%. Value, contrary to popular perception is doing just fine.

Sectors

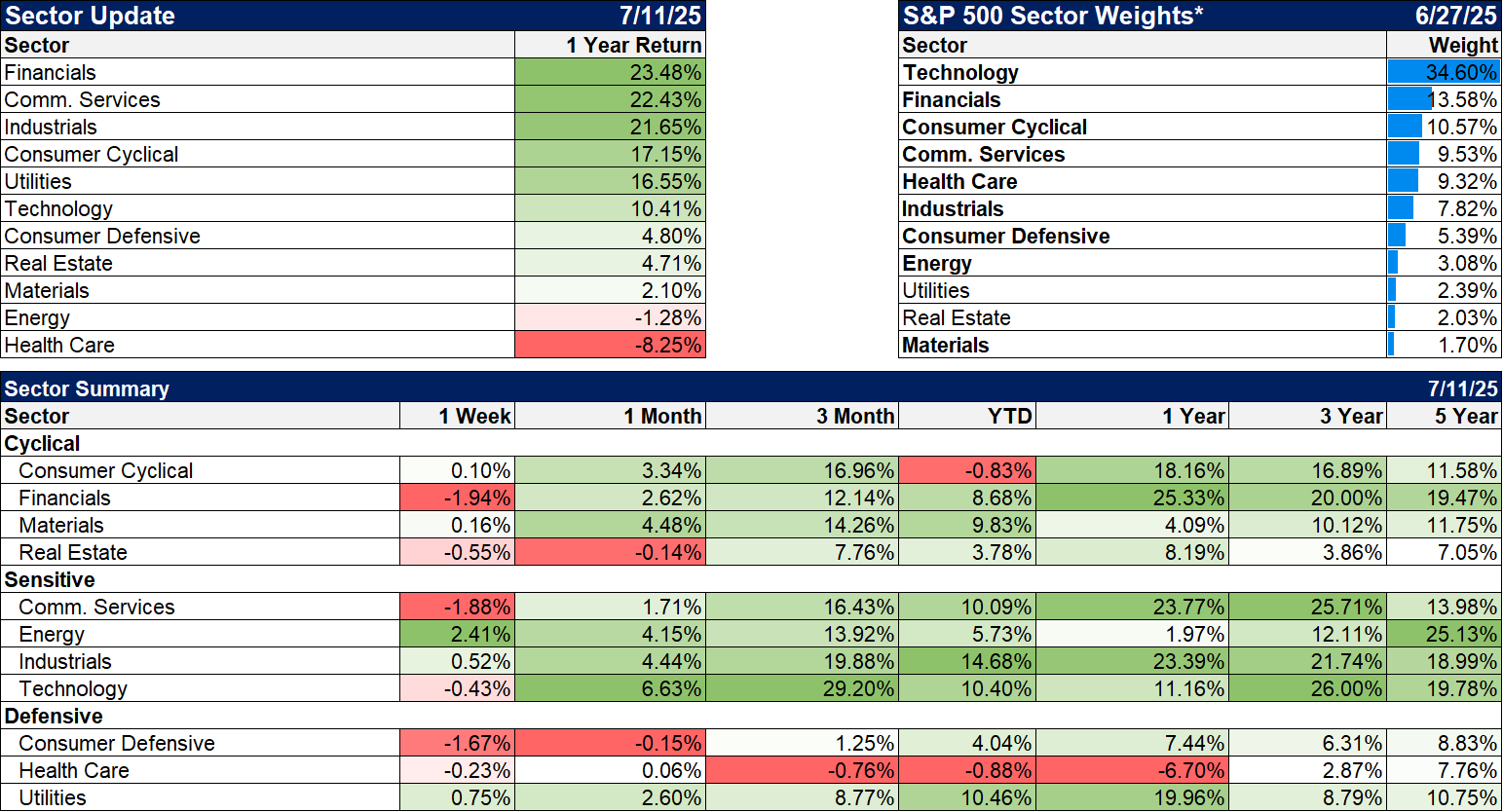

Financials are leading over the last year but technically the sector is very extended. The same is true of Communication services, industrials, and technology. Technically the sectors that look most interesting are hard assets – energy, real estate, and materials.

Economy/Market Indicators

Mortgage rates continue to drift lower but are still too high. The mortgage market index hit its low in October of 2023 and has been climbing steadily but it has been a very slow, torturous process. The index is still at roughly a fourth of its peak value in January 2021.

Economy/Economic Data

There was no economic data released last week of any consequence.

Stay In Touch