Trade between Asia and Europe has dimmed considerably. We know that from the fact Germany and China are the two countries out of the majors struggling the most right now. As a consequence of the slowing, shipping companies have had to make adjustments to their fleet schedules over and above normal seasonal variances.

It was reported last week that Maersk and MPC would “temporarily suspend” their sailings on one of the biggest routes between Europe and Asia.

Weakening demand and plummeting freight rates have so far obliged Asia-North Europe carriers to blank two-thirds more sailings than during the same period of last year, and now the 2M alliance is to suspend the loop for the second consecutive year.

This followed a material downgrade in Mexico, of all places, another economic system highly dependent at the margins on the whims of global trade. At the end of August, Banxico, the colloquial name for the country’s central bank, joined the growing chorus of global policymakers shifting into active “accommodation.” It was Mexico’s first rate cut since 2014.

Mexico’s central bank slashed its growth forecast for this year, predicting the weakest expansion since the 2009 financial crisis amid a slowdown in demand and global and domestic uncertainty.

Everywhere you turn, there are references to global demand while at the same time, by my own unscientific count, fewer and less emphatic protests over trade wars. The latter is still being talked about, of course, but the idea of trade war “sentiment” being the cause of these worldwide woes may be losing steam if only because it just doesn’t add up.

Something else has to be restraining trade well beyond any Chinese goods heading toward the United States waiting to be further tariffed. This is widespread, very close to universal.

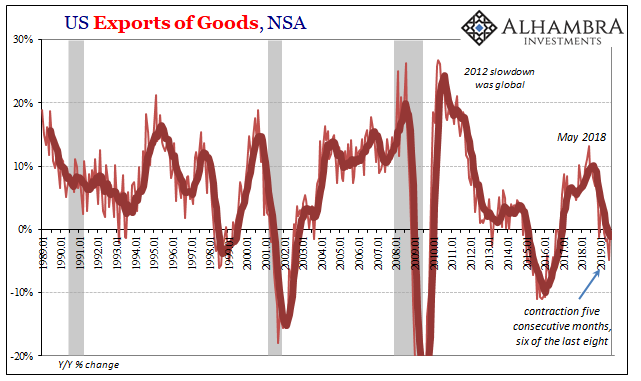

That’s why US exports, for example, are struggling. By conventional terms, that should be the case – the dollar began rising in the middle of last year making US goods less attractive meaning relatively more expensive on world markets. There is a reason why US Presidents claim a strong dollar policy (as if there could be one) in public and in private (and sometimes public) cheer whenever it falls in exchange value.

But as the struggles in the rest of the world show, the American loss is no one’s gain. That’s the part none of them ever get – this isn’t the losing end of beggar-thy-neighbor. The rising dollar leaves no winners in its wake. None.

Rather than redistribute stable purchasing power and reflect strong demand toward relative changes in costs, what’s left is only weakening demand in all cases. Europe, Asia, Central and South America, even the United States.

According to estimates released by the Census Bureau this week, US exports are now routinely falling. Unadjusted, exports to the rest of the world have contracted in each of the last five months (through July 2019). Not by huge amounts, though in June it was just about -5%, more importantly the 6-month average has reached -1.2%.

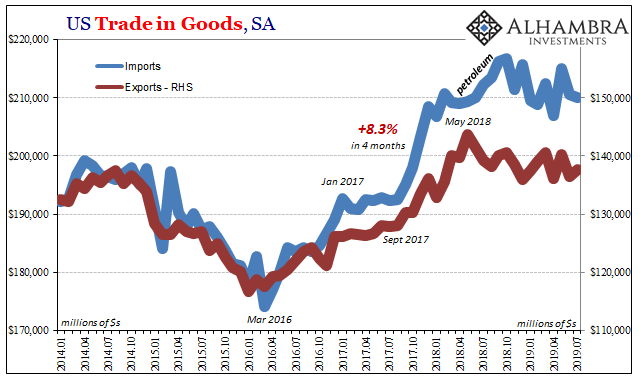

Seasonally-adjusted, the Census Bureau leaves no doubt as to the cause. The peak in the reflation export cycle was unsurprisingly May 2018 (29th). The dollar goes up, and collateral draws tight, global trade suffers not because of trade wars or the cost of US goods relative to alternatives but because the lack of sufficient dollar availability slowly squeezes the life out of global demand.

Trade suffers first because the global reserve currency is its first requirement, the ability to fluently, efficiently translate economic factors from one system to another. There’s almost no appreciation for the functions – and what those actually are – of a global reserve.

We give almost no consideration to what a reserve currency is today. It is almost always thought of in terms of something like oil, the US dollar means people in the United States get to price the vital commodity in their own currency. Some like to talk about a petrodollar as if that actually means something…

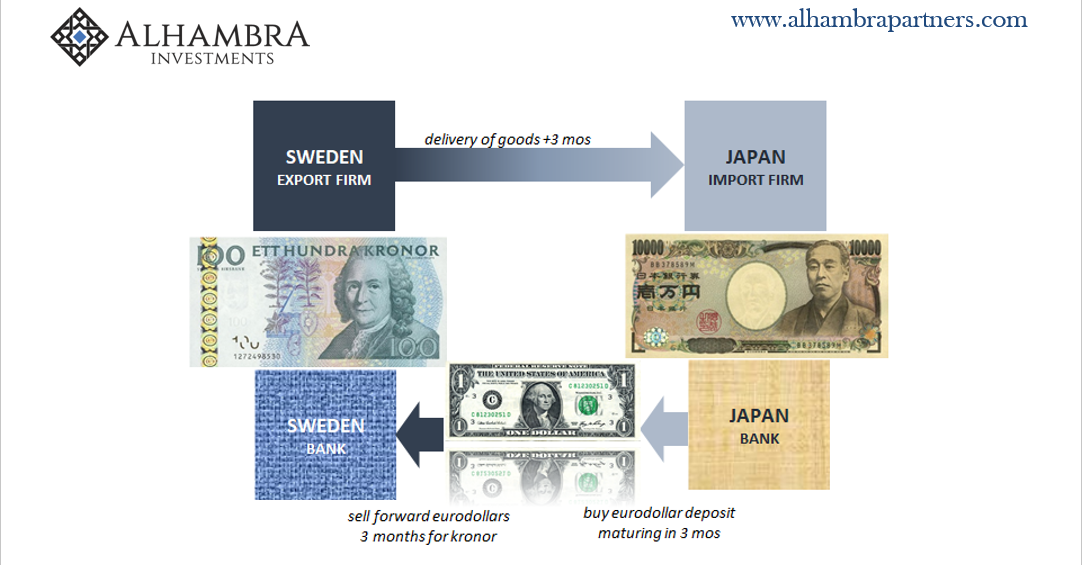

A reserve currency is an intermediator, more than a buffer between national systems often with very little in common. Starting with currency denomination and monetary terms. The example I often use is an export firm in Sweden obtaining goods in that country to be shipped to Japan for final use. The trade can certainly happen without a global reserve, but not efficiently…

If, however, both sides can use a currency that is common in both areas it then obviates the need for either of their national denominations. Should Japanese as well as Swedish banks both hold balances of this middle currency as a regular part of their business, no special concessions required, then trade becomes easy and (very nearly) free.

The downside is that this requires a whole lot of that middle currency to be made available practically everywhere.

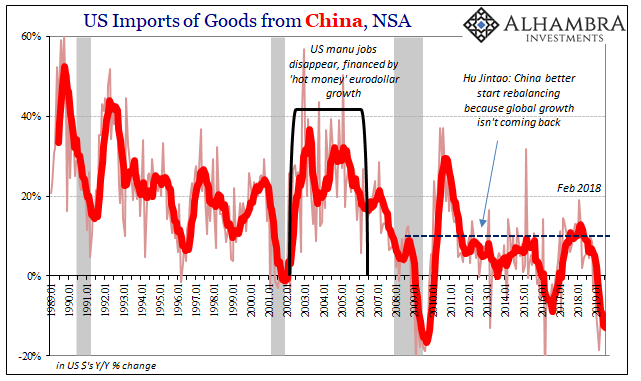

You can then see why global trade downshifted in and around the Great “Recession” and never really came back – though it was predicted to, and everyone especially in the EM’s was counting on it. Before the Global Financial Crisis in that eurodollar system, the middle currency was freely available for use anywhere. Nowadays, it’s so much harder to source and maintain funding.

It doesn’t shut off trade completely, but it does slowly squeeze the life out of it over time. The global regime is starved of its monetary oxygen. That’s why there are no winners; the dollar shortage isn’t a redistribution of demand, it is the slow erosion and even destruction of it (as it infiltrates the supply side, like in China).

We see these same effects on the other side of the US merchandise ledger, too. While American importers are bringing in fewer Chinese goods because they are being marked up by levies, they aren’t making up for them by buying extra anywhere else. Imports into the US are falling as inventory builds up across the domestic supply chain.

The global slowdown is a global slowdown. The monetary squeeze is not entirely fixated on global trade, that’s just where it is most visible and easily discernible. It therefore proposes a far different set of solutions (from a US perspective) than kill the dollar.

If only it was that easy.

MacroVoices @ErikSTownsend and @PatrickCeresna welcome @JeffSnider_AIP and @LukeGromen to the show to discuss the impact of changing Eurodollar markets, the global dollar liquidity shortage and the future changes in global reserve currencies & more.https://t.co/iFqRoKCeVE pic.twitter.com/TXSqKqW2rj

— MacroVoices Podcast (@MacroVoices) September 12, 2019

Stay In Touch