There may yet be bitter irony in the fact that China’s nascent embrace of capitalism in the late eighties allowed it to survive the wave of failed socialist states which fell all throughout the world at the time. While the Berlin Wall came down, the Eastern bloc nearly disappeared, and even the Soviet Union dissolved, the Chinese would stand almost alone as whatever was left of the Communist dream.

But while Beijing had come through in the nineties and transformed China into a modern industrial powerhouse by the middle 2000’s, in late 2008 questions arose as to whether it could survive the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). The one thing the socialists had going for them, what kept the natural unrest associated with strict authoritarianism at bay, was this promise for a glittering future. Not just a promise, one that was being fulfilled in front of the world’s eyes.

The wealth of new China became a deeply rooted expectation. The Chinese people accepted the way things were; a roughshod government in exchange for a middle-class lifestyle if not for them then definitely for their children.

As the GFC “unexpectedly” deepened in late 2007 and early 2008, many came to expect that a robust China would stand firm in the global economy. An anchor of sorts from which the damage might be mitigated (decoupling). It was two problems in one – China’s mighty economy had to save the world and itself.

Those hopes turned to danger after Lehman (really AIG). By November 2008, there was no longer any doubt. Decoupling was dead and serious unrest was unleashed particularly in the areas where the economic miracle had been strongest. Places like Guangdong and the rest of “the Delta.”

In recent months, evaporating export demand had already forced thousands of factories to close in the Pearl River Delta of Southern China. Tens of thousands of jobs have disappeared, leading to protests by unemployed workers demanding back pay.

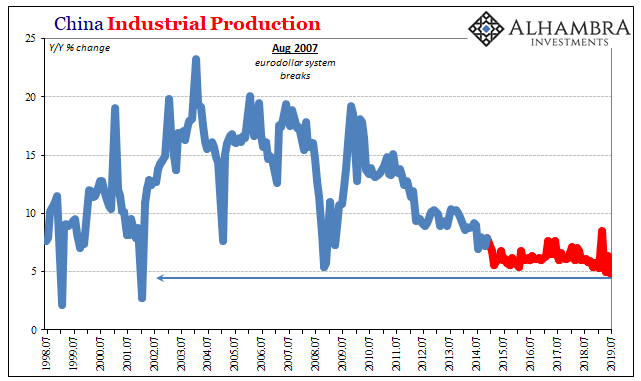

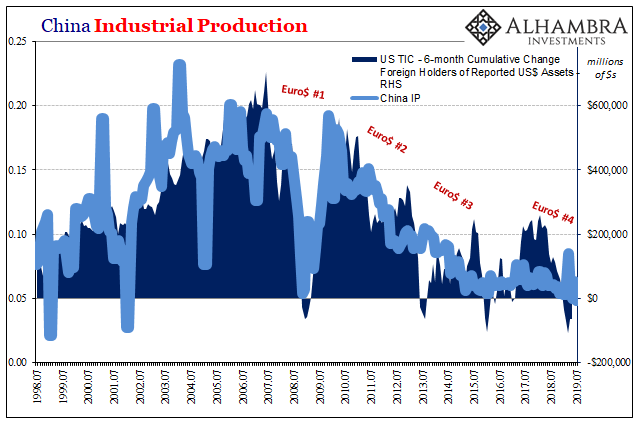

During the month of November 2008, Chinese exports would contract for the first time and Industrial Production would slow to an unthinkably low 5.4% annual rate. It had been taken for granted that all of China’s industry would grow consistently at rates between 15% and 20% maybe forever. Even in March 2008, as Bear Stearns met its effective demise in the stricken “American” system, production had still increased by nearly 18% on the other side of the Pacific.

The Fall of 2008 didn’t prove to be the fall of China’s Communists, but they aren’t out of the woods just yet. Then-Prime Minister Wen Jiabao recognized the danger. He more than anyone began to consider how the government might better de-link China’s economy from the rest of the world.

Even today it seems an insane idea – globalization is like an inevitable force for good, economic and otherwise. The path everyone was following and still wishes to follow had made the world more interconnected, not less.

But Wen sensed the vulnerability. By depending upon the world to buy what China produced, because of the grand economic bargain with its people the security of the Chinese government’s system would effectively be outsourced to that global economy.

The idea of “rebalancing” was by default effectively seeded in November 2008. Using the “stimulus” package announced during that particular month, an enormous $586 billion two-year program, Wen more than anyone made clear its purpose: domestic consumption.

As the global economy recovered from the depths of the Great “Recession”, or at least appeared as if it might, rebalancing was shelved as were any complaints about the dollar. It wasn’t just Americans and Europeans who were giving Western central bankers the benefit of the doubt in the aftermath of the great and global crash. Everyone just wanted to get back to normal, the Chinese Communists most eager of all.

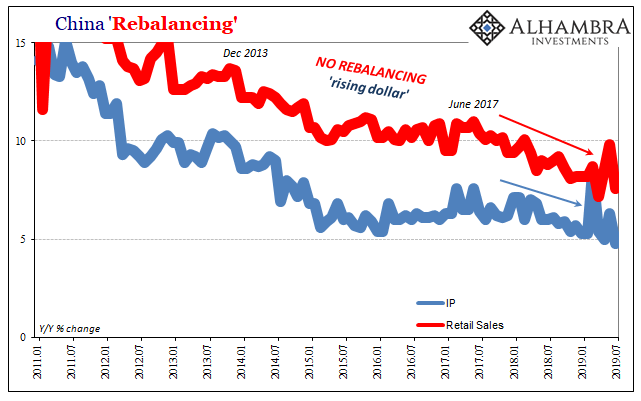

Rebalancing wouldn’t return to the forefront until the 2012 slowdown. This was immediately recognized in China because Chinese officials, unlike their Western counterparts, don’t have the same luxury of self-delusion. It was clear by little more than the operating levels of its economy that radical changes would be required.

The task for the Communists while perfectly straightforward in theory was rife with contradictions and unappreciated setbacks in practice. It sounds easy enough – make China into its own marketplace. If American consumers could no longer be depended upon to buy sufficient quantities, regardless of what the US unemployment rate says, then Chinese consumers would have to take their place.

But how?

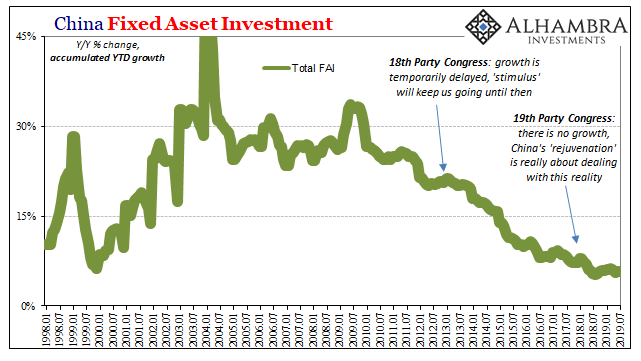

The gathering at the 18th Communist Party Congress in 2012 said it was to be “stimulus.” After a transition period supported and nurtured by further “expansionary” policies, the Chinese economy could be expected to operate almost as normal, just the one exception: selling more goods inside than outside.

It seemed like a risky but attainable goal in 2012. In 2013, however, not so much. What many might remember as the summer of SHIBOR, the coming threat was only then just being teased. The full measure of it only showed up at the end of 2013.

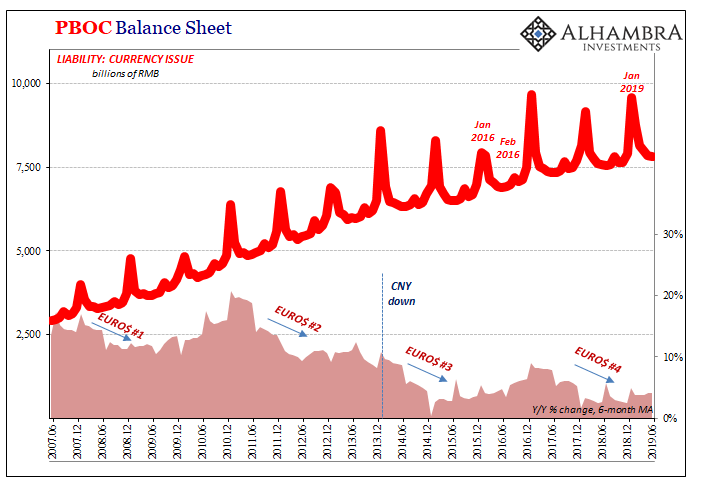

CNY DOWN.

A complete mystery in the Western world, there has been no appreciation for these very real constraints. How does one create an entire internal marketplace almost from scratch while at the same time being handicapped by a monetary system no one had ever expected could be reversed? As the Chinese yuan began to fall early in 2014, what could turn out to be the Communist’s final epoch was set in motion.

Forget all that stuff about the “best jobs market in decades” and Janet Yellen’s carefully dressed giddiness, the Chinese knew it wasn’t real. They could tell 2014 was nothing to get excited about. Not only had the global economy remained stuck in neutral, there was now a growing dollar problem in the very places (EM’s) there was never supposed to be a dollar problem.

Foreign reserves are insurance for that very case – supposedly. That’s what everyone had learned from the Asian Financial Crisis or Asian flu of 1998. So as to inoculate your local system against a funding squeeze, you built up a huge pile of forex reserves.

The Chinese did that and then some. They amassed the biggest stockpile of reserves ever imagined; very nearly $4 trillion at one point. Why didn’t it go as planned?

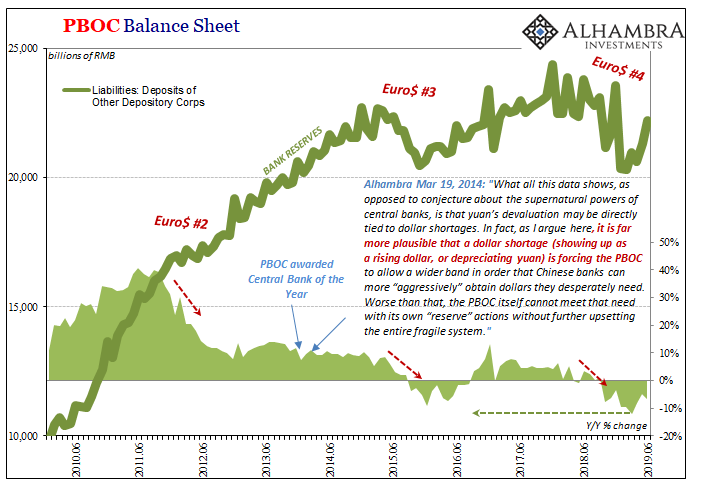

No one ever considers the other side of these “reserves.” There’s no vault containing stacks of foreign cash, nor a lockbox in Beijing stuffed with US Treasury paper. Foreign reserves are not an idle portfolio of custodied assets, either. They had become the very basis of China’s monetary system.

To face a dollar shortage and use those reserves means to purposefully withdraw “base money” in your own backyard. There are tricks and offsets (RRR) available to try and mitigate such tightening, but all those are complicated, convoluted, and no one really knows how they all might work in concert alongside so many other factors – including a global economy which isn’t (ever) performing the way it is supposed to.

In other words, at the very moment the Chinese were counting on rebalancing to keep their internal deal with labor alive they had to start running the money printing press in reverse; effectively choking off the very thing that was supposed to fill in the foreign demand gap and rescue the entire system from the peril only glimpsed for a brief time in 2008.

In early 2016, authorities panicked. A hard landing in China would’ve meant more than just economic costs. While the rest of the world’s Economists were again giddy with globally synchronized growth by 2017, the Chinese knew they had only bought themselves some time; and maybe that’s all they were really hoping to accomplish (the L). The reckoning had only been postponed.

So, the 19th Party Congress in October 2017 was a very different and frightening affair (though only Japanese banks rather than the Western media seemed able to catch their drift). To China’s workers Xi Jinping said “quality” growth had become the country’s new priority. And then Xi set about making himself the unquestioned leader, tightening his grip on the Communist Party apparatus as well as the government.

It is, perhaps, the end of the dream and the breaking of the deal. There is no going back because there is no realistic way back. I wrote in October 2017:

To forbid political challenge to the country’s leadership is one (potential) method for at least raising the costs of turning grave economic dissatisfaction into something more substantial. It seems more and more that authorities over there are battening down the hatches, not opening themselves up in a way that a more optimistic and bright future would lead.

In 2019, all of these negative factors are truly starting to converge for the first time. The lack of external-driven growth; the monetary squeeze further choking off rebalancing; the government’s reactions, bigger and meaner as the economic pressures only build.

What’s going on in Hong Kong is no accident. From the Communist perspective, what better way to display the levers of political control than by suppression of the one administrative district ostensibly free from total control. If they can crush and assimilate Hong Kong, maybe the last bastion of Chinese market ideology, what might the average Chinese think of their own chances? What does Xi want the average Chinese to think about dissent?

It’s been thirty years since a true Communist show of force in China. In between, it was economic growth which had kept the tensions to a reasonable minimum. Take away that growth, and more so take away any hope of resuming growth, devolving into 1989-style repression is how these things go; as I wrote back in 2017, “Economically satisfied citizens are a far better long-term proposition than a politically unstable peasantry prone to fits of righteous anger.”

The latest economic numbers from China bear out the troubling and dangerous pattern. Industrial Production in the month of July 2019 rose just 4.8% year-over-year. Outside of two Golden Week Februaries many years ago, this was effectively the lowest on record; which simply means that China’s industrial sector is now operating at its lowest point, substantially worse than in November 2008.

And it doesn’t appear that it will be getting better.

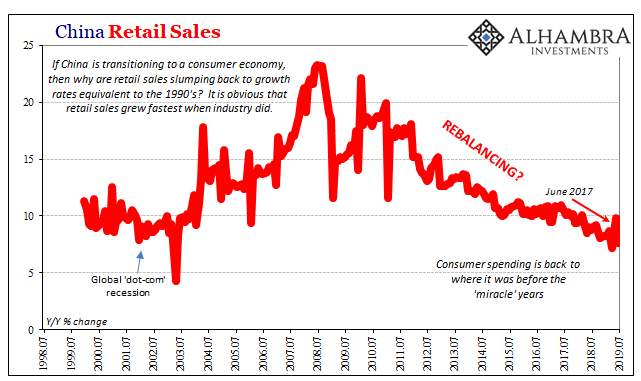

Retail sales gained just 7.6% last month, which outside of a single month in 2003 is the second lowest on record (the other taking place just a few months ago in April 2019).

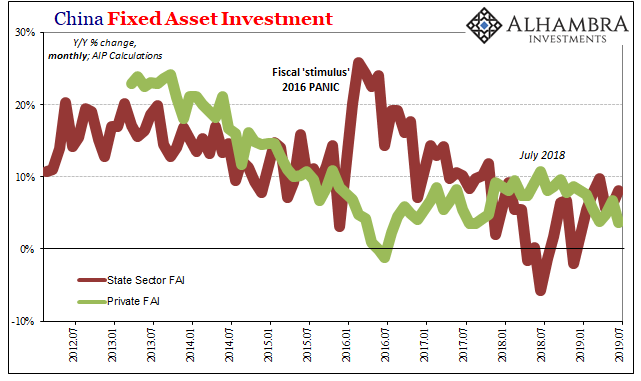

Fixed Asset Investment (FAI) has turned downward again as private Chinese capex continues to soften and authorities are intent only to offset a little of the decline through state-owned businesses.

To survive the aftermath of the late eighties, China’s Communists needed to open up and introduce market reforms. This was a necessary but by itself insufficient condition for economic success – political survival on these terms. They needed the market basis, yes, but China also need the dollars. Without them, the miracle never would’ve happened and who knows what China would have looked like over these two decades they did get them.

Since 2008, China still has the market reforms, even more reform, but not the dollars. There’s really no room to appreciate the irony. Those Communists survived the fall of the Soviet Union on the basis of the dollar, but they might have to really fight this time to survive the fall of the dollar.

We’ve observed political and social discontent the last few years spill over far beyond China. The dollar isn’t just China’s problem, nor is it really America’s. It is everyone’s problem – which is why there are problems everywhere – and it’s the one thing nobody seems to recognize as behind all of it. That’s the real tragedy; it’s not difficult to translate.

Stay In Touch