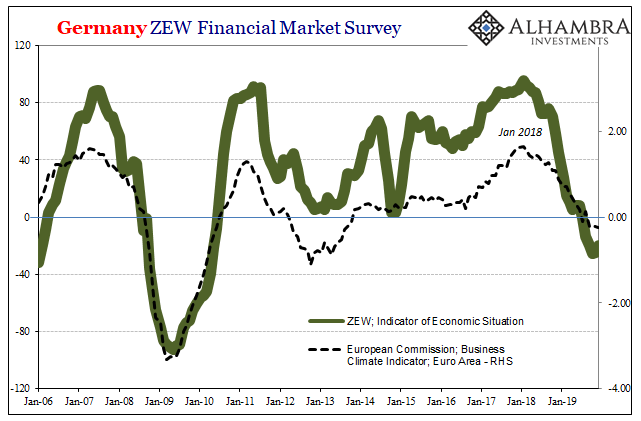

It’s a palpable impatience. Having learned absolutely nothing from the most recent German example, there’s this pervasive belief that if the economy hasn’t fallen apart by now it must be going the other way. The right way. Those are the only two options for mainstream analysis (which means it isn’t analysis).

You can see it in how everything is framed. When first presented with this “unexpected” globally synchronized downturn early on in 2019 (they ignored all the market warnings and data throughout 2018), it was dismissed as the product of “transitory” factors. Once they dissipated it would be all clear. Anyone remember the constant projections for a second half rebound?

The second half has come and is now long gone, and we are still debating the direction.

Those forecasts were predicated on the assumption this is the dynamic. A downturn comes on and develops quickly. After a few months, either recession or right back to growth again (the near miss, or growth scare scenario).

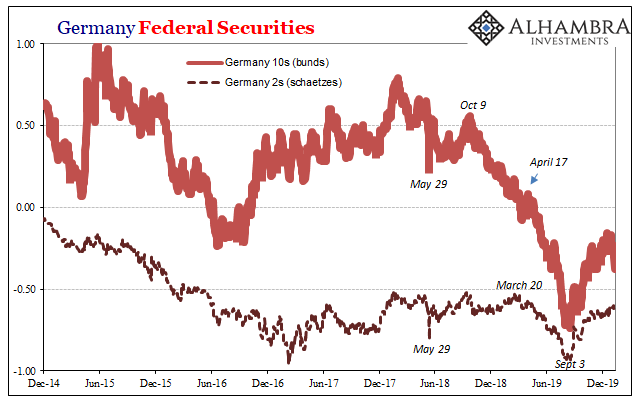

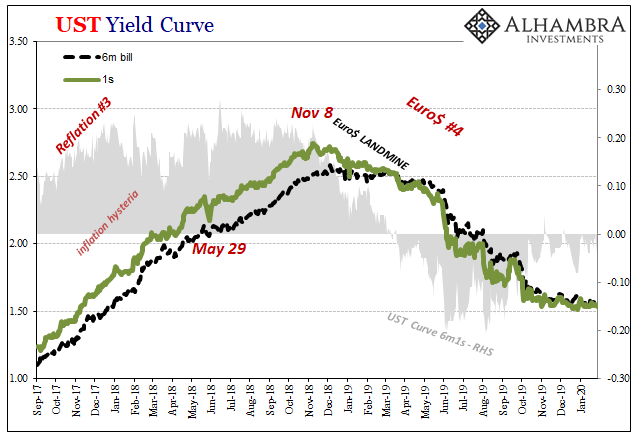

It all came to a head in August and right at the beginning of September (a few weeks before repo; hmmm). The way the bond market was described, curve inversion was an all-or-nothing threshold. If the economy didn’t right then enter recession it was assumed it never would.

Thus, as the curve un-inverted (in the one place anyone pays attention to) the second half rebound was given its market backing. The economy had backed away from the edge, which, in the conventional view, means we have to be back on the right track.

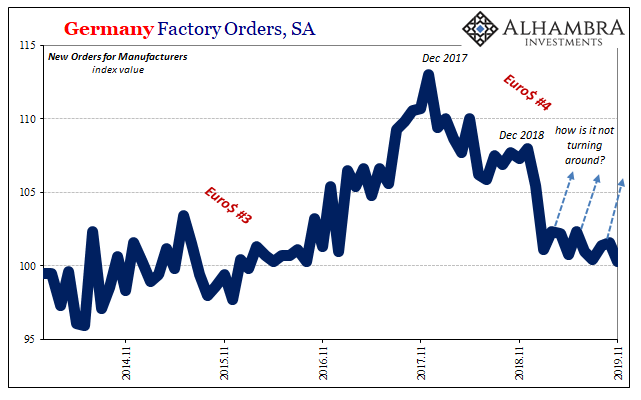

But that’s not at all how it has gone in Germany (and many other places). German industry didn’t crash in a violent downswing, yet it has reached those proportions along the X axis. The depths of something consistent with recession have been achieved, but it took seemingly forever to get there.

Not only that, once it attained those depths German manufacturing in particular has remained at them. Time, the Y axis, appears to be no constraint, an outcome which defies the conventional view of it-has-to-be-recession-or-boom.

It is a squeeze, a drawn-out process which slowly but steadily and increasingly deprives the economic system of its monetary oxygen. As such, it can – and so often does – go on far longer than it “should” under the mainstream binary growth model.

This is therefore different than the “shock” which orthodox Economics assumes precedes recession. You have growth at all times and if suddenly you don’t it is only because of a substantial shock which temporarily depresses activity and output. That’s a recession. There’s no room in this model for something like a sustained squeeze.

Yet, that’s what keeps happening.

That second half rebound in the US has now been replaced; or, more accurately, moved in time to the first half of this year. Thus, all the proclamations about 2020 having begun on the right foot – without ever explaining why both feet weren’t already moving the right way in the last half of 2019 as was predicted.

Month after month, the downturn just lingers. As it does, it confounds the narrative as well as raises the risks; the recession risks that do arise where the squeeze will eventually either create a shock or qualify as one by leading to the same second and third order effects that you would normally associate with it.

That’s what happened in Germany; there didn’t seem to be any shock and after two years of this slow drain German industry finds itself as if there had been. Recession proportions that, as time goes on and the squeeze remains unanswered, threaten to do more than just put manufacturing into that negative category.

Is Germany an outlier, or a glimpse of what lies ahead for the US economy? If the latter, then the American system is simply following down the same road just coming up behind.

The data we have continues to suggest there will be no decoupling. The narrative has shifted but the evidence has not.

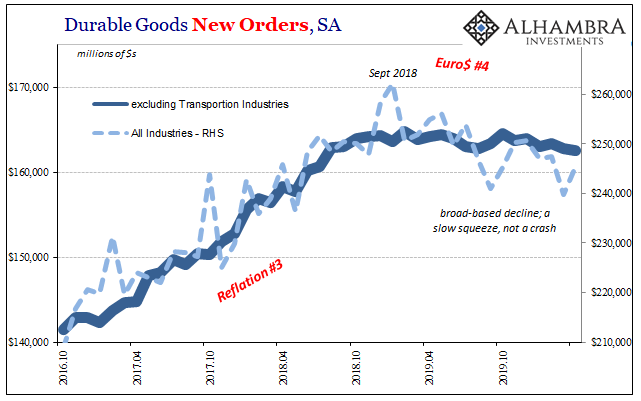

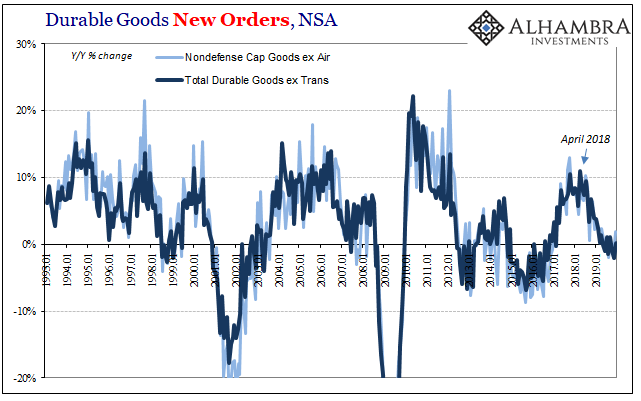

The latest is durable goods. As you can see, nothing has changed. Going back to the latter part of 2018, the trend remains downward. Not a crash, but the slow, diseased path of a system being deprived of its vitality. By something still unanswered.

No second half rebound anywhere. And no, 2019 didn’t end in the way which would set up 2020 for a substantially different course.

This is all just what the bond curves have been saying all along. Forget the August 2s10s inversion for a moment; the yield curve, the whole thing, merely pointed out that as far back as November 2018 economic risks have been rising. The downside, whatever that might mean, was coming to fruition.

Just as it did. What the bond curve now says is that it isn’t likely done. Not yet. The downside risks remain the more likely scenario, if not quite as likely (and scary) as it might’ve appeared in late August.

Thus, despite all the things which were supposed to have been late-2019 game-changers, from Europe’s restarted QE (if you have to do it more than once…) to trade deals, rate cuts, and stock prices, the bond market really hasn’t bought into it.

Even the rate cuts aren’t what they may seem. That little wrinkle in the curve shown above is a projection of the current balance in risks; there’s a modestly higher risk of more rate cuts to follow this year. That’s what the inversion in the short belly says; the same as when it first developed late in 2018.

It is and has been an assumption that a turnaround is associated with time. A recession has only a narrow window; it shows up during it, or it never will. That’s just not true and we can see the data displaying much the same thing all over the world. The US continues to be stuck in the squeeze, too.

And that was before the coronavirus.

Stay In Touch