Never one to miss a chance to prove how much Keynesian philosophy and monetarism are compatible, the AEI (a think dedicated to American Enterprise?) and James Pethokoukis would like you to know just how much QE “worked.” The logical and empirical “proof” of that efficacy, and thus why you should “thank” Ben Bernanke at the same time Yellen’s FOMC is dismantling his entire philosophy, is Europe.

Many conservatives loved pointing to Europe when its debt crisis seemed to be spiraling out of control. A cautionary tale, they said, of what can happen when government spending goes wild. But they had the story wrong, or at least incomplete. Europe’s sovereign debt crisis was as much about slow growth as high debt. Anyway, these folks don’t talk much about Europe any more. And maybe that’s because it is now a cautionary tale of what happens when you combine fiscal austerity and tight money.

To get there requires only a simple exposition, courtesy of Michael Darda, an economist at MKM Partners:

The US and the UK have dramatically outperformed the EZ over the last four years despite even more contractionary fiscal policy. This can only be explained by differing central bank policies, in our view.

There is nothing an orthodox economist likes more than to point to “tight” policy and see “deflation.” I would be far more convinced of this interpretation if Mr. Pethokoukis, or anyone at the AEI or any orthodox economist for that matter, could point to this “tight” policy constraint within Zoltan Pozsar’s “map” of the modern financial system. Was it the herding of dealers into QE-sized ubiquitous and uniform positions in IR swaps? Or perhaps the eurodollar market’s comparative erosion from European perceptions? None of those factors account in Pethokoukis’ world of “tight” and “loose” generic settings.

But staying within the simple, generic and ultimately stylized world that they present here, what about Japan? It is curious that the US and EZ are left in single comparison without bringing in the Bank of Japan’s ultra-“loose” monetarism that would certainly fit their beckoning. To ask that question is to answer it, especially given what has transpired via “loose” monetary policy in Japan these past eighteen months.

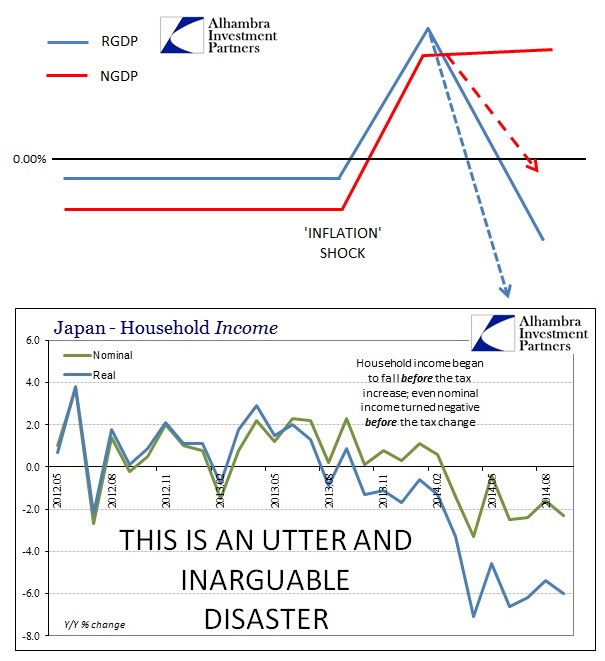

I think the template I used to “forecast” Japan’s track is somewhat useful in illustrating what the AEI is trying to force the data to see. In Japan’s case, the shock of “loose” monetary policy via QQE unleashed exactly the “inflation” orthodox economists (and those calling themselves “market monetarists”) have been looking for. But instead of bringing about a full recovery of unmistakably broad and positive effects, Japan simply flipped from contraction via “deflation” to worse contraction via “inflation.”

There will be the impulse, which is already growing, to move the goalposts for QQE and place all blame on the tax increase. That makes little actual sense given that the tax increase was implemented solely because it was believed QQE had already “worked” when it clearly did not (the decay in Japanese results, especially trade, began long before the tax hike).

Getting back to the AEI position, they apparently see the same ideas but expressed in different proportions.

The trouble with the ECB, according to this interpretation, is that though it “tried” the “loose” policy road it was not enough; thus overall policy positioning remained effectively “tight.” To the market monetarist, apparently, that explains Europe’s most recent descent.

Even taking into account the deficient results in actual growth in the US, QE is judged here to have been effective because it was slightly more “inflationary” than Europe. Where the Fed was “more loose” compared to the ECB, the US economy gained that benefit by remaining on a steady, though unsatisfactory, course.

However, Mr. Pethokoukis and Mr. Darda are making a temporal mistake. Steady growth right now is very misleading, just as it was in 2007 heading into 2008. Slow but “steady” growth is actually nothing like that but instead the elongated business cycle playing against historical, archetype expectations. Instead, improving the timeline to view this modern “cycle”, the US may not be all that different from Europe save only the temporary “boost” of “loose” policy losing its efficacy and imprint over more time.

In that respect, the US and Europe are only different from Japan in intensity and the time it takes for ineffectiveness to show up after temporary gains wither.

In other words, we all end up in the same place, but the differences in concentration (and you have to account for initial conditions, which they intentionally ignore) lead to only dichotomy in ultimately how long it takes to get to that same endpoint. It does not matter when each program began, or when each central bank carried out the same “loosening” over and over and over, the track of “inflation” discounts this “market monetarism” interpretation to zero.

Monetarists, in this age of growing unease over central bank efficacy, are simply confirming that nervousness by degrading the standards by which they wish to be judged. Ben Bernanke, for his part, was unequivocal in where he thought QE would lead, and it wasn’t to settle for “at least we are not Europe” – to which it may be appropriate to add “yet.”

Stay In Touch