Though it is now more than four months into the past, the events of October 15 remain relevant and will likely stay that way for some time to come. The mainstream seems to have made peace with the idea of electronic trading in some primordial state in treasury markets, but to anyone with even a little knowledge of credit markets such an excuse just doesn’t even come close to laying out all that went wrong. Again, a buying “panic” is still illiquidity, an event that is and should be highly concerning to just about everybody as the modern financial system is utterly dependent on financialism performing to a high degree.

My good friend Wladimir K. passed along a terrific piece written at risk.net headlined The Makings of a Treasury Market Meltdown. Author Kris Devasabai puts together a lot of different pieces to reconstruct October 15 from the inside – and the words “electronic trading” don’t appear. Essentially, there was a confluence of trends that received augmentation by specific events clustered at the end of September and into early October. In the article, Devasabai looks at Bill Gross’ departure from PIMCO and a radical alteration in bond strategy as it related to “gamma trading”, as well as the failure of the pharma merger between AbbVie and Shire, as a catalyst to setting in motion powerful negative forces that ended up reshuffling the entire global financial system.

As I said above, it is a tremendous story even though I don’t necessarily agree with all of it as it relates to putting all the pieces together (I think the appeal to PIMCO is a bit overdone, and there isn’t any mention of high yield credit and leverage). Even with that in mind, the essential element emerges as liquidity now relates to something far less tangible than anyone seems to appreciate (or, at least, so very few to be dangerous, including a huge lack of awareness in policymaking). You don’t need to go into all the details about the “gamma trap” or even to know much about gamma itself to understand the consequences of this kind of leading emphasis:

“The only way this happened is that someone got very, very short gamma. You don’t get a move like that in a linear product,” says one bank’s European head of flow rates trading…

“Part of the effect was hedgers not being able to hedge. If someone is reversing short gamma positions, it means the counterparties to those positions face losses in a big move, so they are forced to trade with any trend,” says a senior executive at a US asset manager.

The effects of balance sheet mechanics into October 15, for whatever proximate cause ultimately, meant the dreaded crowded trade unwinding all at once. There are supposed to be dealers intermediating those trades, but as I have contended for a long time the dealers aren’t really dealers anymore – they are speculators not unlike all the rest. And so it is very possible that dealers were caught up in being on the “wrong” side of the “gamma trap” as well as any of those hated and derided hedge funds.

In one telling part, right of the climax of October 15, Devasabai writes succinctly what has become of the “modern” financial system and the “dollar” (my addition):

Dealers, meanwhile, were scrambling to cover their short gamma exposure because Pimco and other bond firms were no longer selling volatility.

This gets back to my post on Complex Interbank Math, in that what dealers provide to “markets” are not reserves or even “dollars”, but rather “risk units.” In the case of October 15, without PIMCO and others “selling volatility”, which was a “reach for yield”-type strategy of “enhancing” alpha, the system shut down for nearly an hour. There were plenty of “dollars” available but no means by which flow would be created in order to keep and maintain order. There is something distinctly distressing when “gamma” is the primary concern between orderly markets and almost full chaos; even if only for an hour or so, which is all that it takes. In some sense, we were “lucky” that it was a buying “panic” and not outright selling, as a rise in interest rates under such illiquidity might have triggered the worst case.

The article quotes an insider’s view, which almost perfectly sums up what has happened in the past few years:

“There is no ability to really understand much of the dynamics of this market anymore,” says the international bank’s head of global markets. “We used to be able to tell regulators, five years ago, ‘We know where the bodies are buried, we know who has the risk’. That’s not true anymore and risk capacity has been soaked up by predatory buy-side firms – with lots of lawyers – and their commercial interest is not to make markets more stable; it is to make the market more unstable.”

So where the article does a good job of providing an anecdotal summation of one potential entry point of disorder, and the combination of various local events, the larger questions are still “how” and “why”. There cannot be any denying that central banking in this current era is the central impetus behind this massive shift.

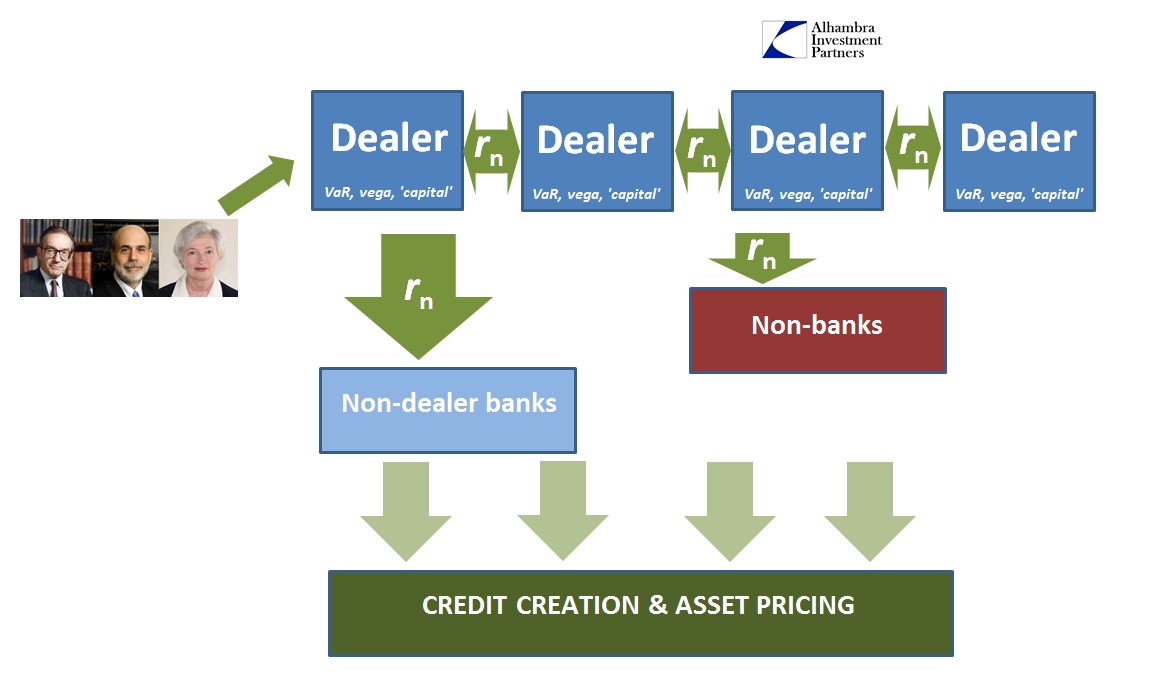

Official commentary always seems to perceive dealers as if they are supposed to function as an almost “neutral” provision – historically that was the case, but much longer ago than you might think. Furthermore, even the more complex of evolving official understanding about the subject of liquidity finds dealers as not just neutral but split between bond or credit trading and derivatives dealing. These are not just false assumptions, they are dangerously so. This is also a persistent theme that has come up before:

Again, I think there is a great deal of merit in how Mr. Pozsar presents his view, but that it is still dangerously incomplete (again, with much respect for the tremendous effort and what was accomplished). I would include in that criticism the continued tendency to stylize and compartmentalize (which may just be unavoidable), not just in the global dollar system as presented here but also the dealer system which for some reason always seems to split securities “flow” from derivatives (they are all one) and to assume dealers are neutral (always a matched book).

Not only is there no break between bond dealing and derivatives, as they are inextricably intertwined, dealers are no longer neutral to the system. They still provide liquidity but the repression of interest rates in this age (which predates the 2008 panic) has made bank “capital” far too expensive to operate efficiently under “neutrality.” Thus even financial firms that “should” be strictly dealers or acting exclusively in a dealer capacity are now, again, as speculators like anyone else (this trend also encompasses more evolved portfolio views on the part of banks which incorporate all activities together). Selling volatility may be a liquidity-providing activity, but it also expresses a specific view of profitability in that position rather than strictly providing liquidity.

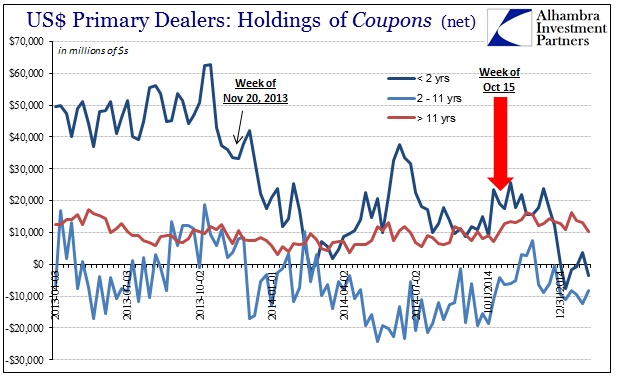

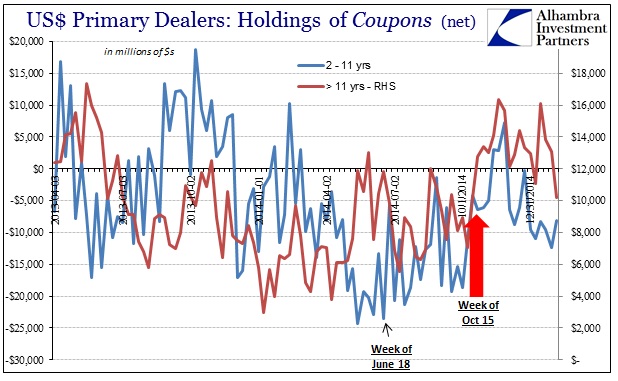

In the past few years, that speculation has run much tighter together as again the Federal Reserve has intruded upon credit markets by first taper and now more current threats to raise interest rates. The net effect on just dealer activity has been clear and stark.

What was a huge long position in shorter-term UST (not bills) under 2-years suddenly shifted after the violent 2013 selloff to a far more neutral position. Was that due to dealers reacting to “market” conditions of appetite surrounding perceptions of credit, or a repositioning “to trade” based on expectations of adjustments in Fed policy? Furthermore, by the middle of 2014, dealers were short, net, longer-dated coupons to a significant degree.

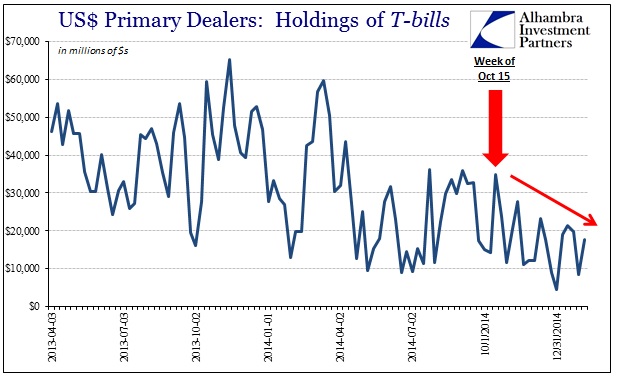

When the first repo disruption occurred in mid-June, dealers were totally unprepared for that event and thus added little to dispel the disruption despite expectations of their role. Starting in early October, as liquidity became acutely severe, dealers clearly shifted more toward a neutral position in notes and a more long position in bonds – and out of bills (below).

To my mind, that is confirmation of what was noted above, as dealers were also “caught” in the wrong position not only to provide little “liquidity” aid to these ailing markets, but also as a full participant in the short treasury trade (and all the one-sided derivatives that went along with it); taking pain along the way. You can’t act as liquidity provider where you are also trying to square your positions with the rest of the “market” to a less risky view due to accumulating losses.

If rate repression is as powerful as it seems, perhaps there should not be much surprise when even basic dealer activities have been bastardized (like every other “good” idea in finance) to become just the latest incarnation of speculative activities toward boosting profitability in a regime where capital is just too expensive by proxy (of rate repression). This is exactly the same kind of behavior as what took dealer activities in credit production to an almost existential decay by 2008 – simple dealer warehousing of securities in the late 1990’s and mid-2000’s was beset by “over”-hedging in what was really speculative profit-seeking, or prop trading at its worst.

We know from recent surveys, passed along via ZeroHedge, that there has been a significant shift in derivatives trading itself, morphing from strictly or mostly hedging to pure speculation. Given what we see here, and of October 15, I think we can easily add dealer activities to that process. That is an entirely unwelcome development, as the combination of central bank pressure through repression, central bank interference in threatening policy changes and dealers no longer acting much like dealers are “supposed to” (or at least expected to) is a very dangerous combination. Recency bias infects almost every discussion about these outcomes, as most simply ignore it as “nothing bad has happened so nothing bad will happen” – the same prevailing attitude during the late stages of the housing bubble and early stages of the housing bust. Unfortunately, even October 15 is set aside under that interpretation as “we survived so it doesn’t matter.”

The primary factor behind all of this is large, even unthinkable, financial imbalances. Liquidity is not just important where imbalances are severe, liquidity is paramount as pricing effects everything including the ability of a system in such a critical state to continue to function without phase shift. Everything we have seen in the past few years indicates decay to the liquidity function which so many market participants simply ignore, and policymakers simply don’t understand (or want to). If “gamma” can cause a meltdown the size of October 15, then we are in an entirely new ballgame where nobody really knows the rules, but everybody still thinks they do.

Stay In Touch