The world of orthodox economics is populated by generic assumptions. The biggest and most dangerous is that of “aggregate demand” which posits that any economic activity is perfectly substituted for any other economic activity. Since there is no distinction among “what” is taking place and more importantly “why”, that has led economic policy and especially monetary policy toward command management. If it doesn’t matter the impetus or the expression for individual transactions, only their aggregated quantity, then so much the simpler for control.

That last part is derived from the regression equations that govern “general equilibrium” theory. The details of all that are vitally important to understanding why policymakers do what they do, but the implications are easily digestible without undertaking dalliance with statistical theory and mathematical limitations. Suffice to say, you don’t need to know exactly why rational expectations theory is a forced equality to obtain a general equilibrium state in order to intuitively sense its awkwardness and loose familiarity with real economic function and how that might lead policy far, far astray.

The combined nature of these theories is that a central bank can convey “stimulus.” That simply means, since activity is all equally substitutable, the theory applies to activity that does not take place. In other words, if the quantified level of transactions is deemed “deficient” by orthodox economic understanding of generalized econometrics (setting aside any realistic ability to define and precisely measure such variables) then a central bank can engage in measures to “create” “demand” that “should” take place. In basic intuition, they create transactions for the sake of transactions with the idea that simply “putting money to work” will eventually lead back to true economic potential.

This is the modern essence of Keynes’ “pump priming” where government or debt-based private “demand”, fueled by monetary cheapening, is the only course out of recession or an economic rut. No thought is given about how such top-down introductions might alter the natural economic course, as true capitalism is driven not by generic “demand” but by perceptions of sustainable profitability, because of these general equilibrium assumptions. If an asset bubble forms and leads millions of people into day trading instead of STEM, millions of lawyers and mathematicians to Wall Street instead of industry, both “saltwater” and “freshwater” economists are perfectly happy because people are doing “something”; and that something gets reflected mathematically into GDP and the unemployment rate.

“Demand” that may arise from central planning of this type may not be at all like “demand” that occurs organically along actual market-driven profitability. Further, the accumulation of this altered state of “demand” just may place a burden upon potential economic function due its highly inefficient creation and maintenance (especially where failure is rarely allowed). Even at that first instance, if there is a deficiency in “demand” it may very well be that is the preferable course, as creative destruction has a vital role in true capitalism.

Interfering within the natural course may not be detectable in that short run, which is precisely the deficiency in the broad measurements we take. It is impossible to infer, model or extract counterfactuals based on what “should” have happened had a central bank or economic authority never interfered. Instead, we are left pondering why the economy fails, time and again, to deliver what it used to with regularity.

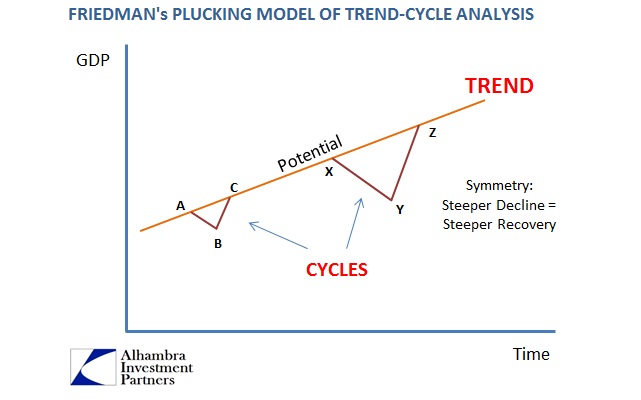

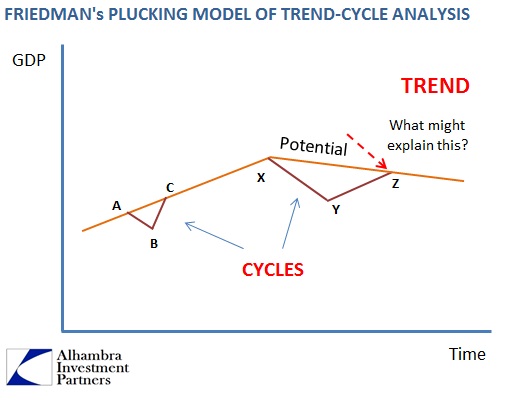

These breaking correlations among expectations and actual results have been a feature of the current economic “cycle”, as Milton Friedman’s plucking model, for the first time, failed. It used to be that the speed and scope of the recovery were determined by the size of the contraction, a symmetry that makes common as well as theoretical sense. The Great Recession, then, should have given way to the Great Recovery – one that would have put even the early-to-mid 1980’s to shame. Instead, seven years to the day that Bear Stearns failed and Ben Bernanke and his FOMC were so sure we had seen the worst, we are still debating a “recovery” at all and where it might have gone so persistently wrong.

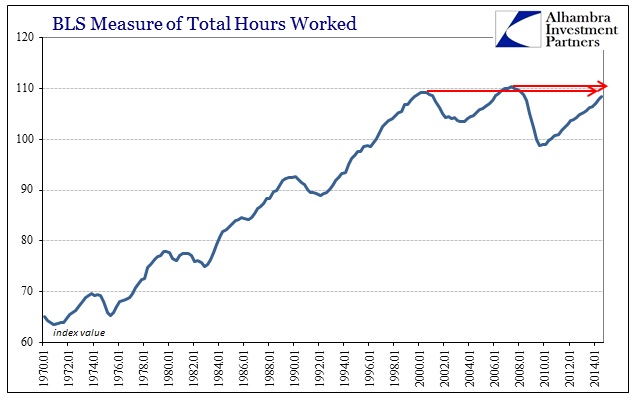

The most relevant argument in 2015 is how the Establishment Survey is so terribly alone in its version of the economy. It was believed an unquestioned “law” of economics that if payrolls are growing so is the overall economy; thus if payrolls are expanding at the fastest pace in decades there should be proportionality of everything else, especially wages. Yet, even the FOMC will admit wages lag, but the degree to which they remain stuck again suggests more basic depredations than anything offered by the same policy repeated again and again and again (and again).

Six years into the U.S. expansion, the link between falling unemployment and rising wages — once almost as basic to economic theory as supply and demand — seems to be coming unhinged.

The disconnect is puzzling to people like Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper. With one of the best growth rates among the 50 states, a population that’s younger and better educated than the nation’s and a jobless level that’s fallen further and faster than the national average, Colorado seems to have everything going for it.

Yet the rise in the state’s median wage since the recession ended in mid-2009 has averaged just 1.1 percent a year, based on data from the federal government’s Current Population Survey. That’s no better than the lackluster 1-percent-to-2-percent national pace. What gives?

As this Bloomberg article makes plain, the basic assumptions about economic function are not just deficient but almost inverted.

The divergence is even more pronounced at the state level. Wages aren’t growing faster in states with lower, sometimes substantially lower, jobless rates than the nation’s. They’re also not rising nearly as fast as they did at similar points in the past. In fact, the link between state unemployment rates and wages, which weakened during the 1990s and 2000s expansions, is fraying still further this time around.

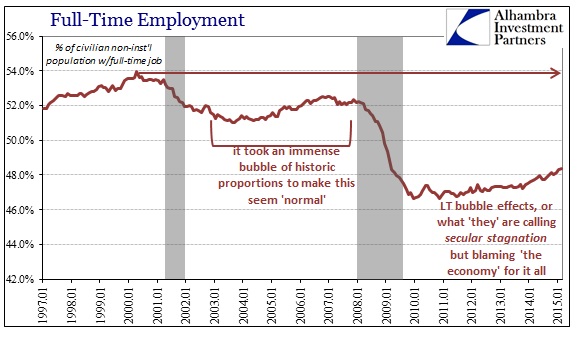

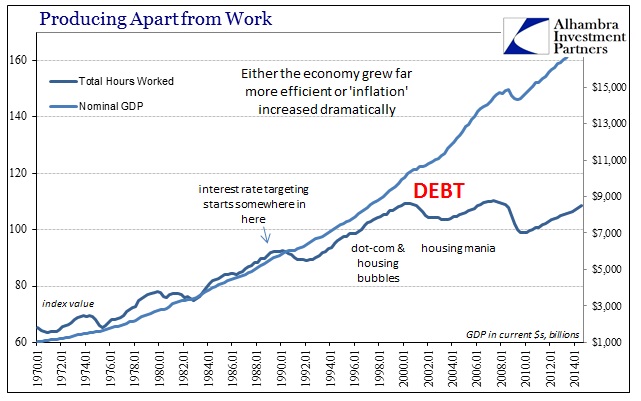

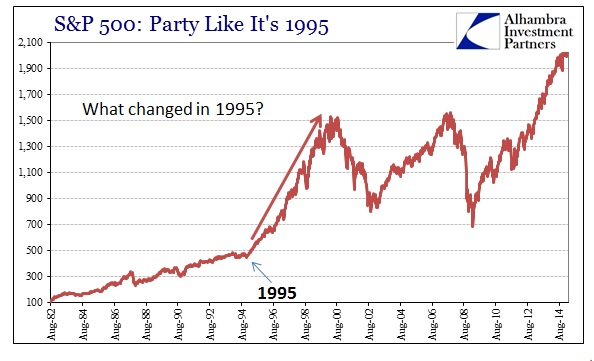

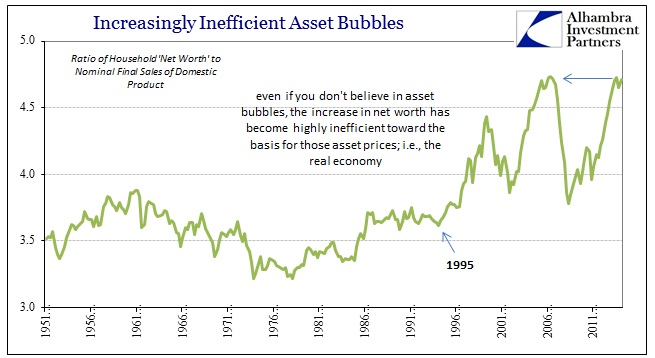

If only there was some dramatic change in economic visibility around the late 1990’s and early 2000’s? The one element that is most obvious to the naked perception of the US economy (and actually the world) is the one factor that general equilibrium as it has existed since 1972 expressly forbids recognizing. Rational expectations theory, in order to make the equations balance and work, “means” there are no asset bubbles because it is assumed that all markets are perfectly efficient. And like perfectly substitutable generic demand, monetary policy and theory actively pursues just such degradation because it is this heightened element of believed-control (owing to the related assumption about monetary neutrality).

It is extremely easy to grasp how not just an asset bubble but serial bubbles may alter the basic behavior of economic function beyond just the short run. Serial bubbles of immensity and out of all proportion to imagination would believably change any number of economic factors especially as they relate to financial profitability (“easy money”) against actual work and the long-term deliverance of main industry. If you heighten the sensation for “money” made without exertion, delivered with lightning speed, the very economic expectations that supposedly define prior structures and incentives within true capitalism will mal-form as a matter of basic humanity.

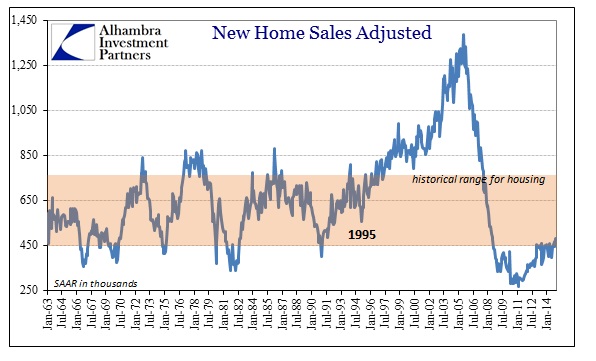

In other words, the economy becomes so addicted to bubbles that it can no longer “function” without them, as marginal function becomes itself an expression of bubbles in themselves. We know this very well since there has been no massive housing bubble since 2009 to “produce”, highly inefficiently, spendable debt to recreate the 2000’s. Since housing has always been the primary monetary channel, the 2010’s are more about asset prices without even these expected economic transactions. And this is not limited to just households and consumers, particularly as corporate business explodes with financial redistribution.

Read the rest of that Bloomberg article, the word “bubble” appears exactly nowhere. Instead, the economists quoted are obsessed with the Phillips curve or “slack.” None of them wish to see the obvious because they “can’t” or else all general equilibrium models would fail. The major inflection in economic function obviously coincides exactly with the arrival of serial asset bubbles. Extrapolating to our current problems requires no leap of faith, only the recognitions that two decades of them have could very well have withered actual function so severely.

Where is all the wage growth? Look below; it increasingly takes the form of asset inflation, and asset inflation alone.

Stay In Touch