Even factoring different sources, there is a decided bi-polar nature to views on Europe’s “recovery.” The slightest deviation from the straight, upward extrapolations of economists is cause for serious self-reflection of Europe internally. That should not be so unexpected, particularly given how economists have completely missed everything since 2007 (anyone remember de-coupling?). But with the ECB’s new QE, there is a palpably sharper edge in the frantic assignments of just bland description.

Last week, those loved/unloved PMI’s were cause for great concern. Coming in lower instead of continued upward sentiment, the faith in the gathering narrative of “nothing to worry about” was seriously set back.

“Disappointing overall but not disastrous,” said Howard Archer, chief European economist at IHS Global Insight, in a note. “Euro zone manufacturing and services expansion unexpectedly moderated in April according to the purchasing managers, perhaps providing a reality check on the strength of the region’s upturn.”

“We also had the reading from France and the French manufacturing and services PMI data has done what it does the best – disappoint investors to their core,” said Naseem Aslam, chief market analyst at AvaTrade, in a note.

And from Reuter’s version of the PMIs:

A sudden drop in the euro zone flash composite Markit Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) was driven by sharply slower growth in manufacturing orders in Germany and France, suggesting recent optimism about the euro zone may be overdone…

This marks the first major euro zone indicator that has disappointed all forecasts in quite some time, and comes just a month after the European Central Bank began purchasing government bonds to stimulate the economy.

Factory order growth slowed particularly in France, but also in major exporter Germany, the euro zone’s No. 1 economy, suggesting more subdued activity ahead.

It didn’t help that China’s PMI similarly boosted concerns for the “global growth” appeal that is supposed to end all this economic misery, but those concerns lasted all but a few days. They are now seemingly all set aside because there was private loan growth in the Eurozone for the first time in 3 years. Of course, anything positive will be described as relating to QE, such is the almost need to believe it will work where everything else to this point has not.

Bank lending increased 0.1 percent in March from a year earlier, the ECB said in a statement on Wednesday. Loans had posted annual declines in every month since May 2012. Lending climbed 0.2 percent from February…

“With its more aggressive stance, the ECB is finally bringing the euro zone back to at least trend growth,” said Holger Schmieding, chief economist at Berenberg Bank in London. “Money and credit point to a firming business cycle.”

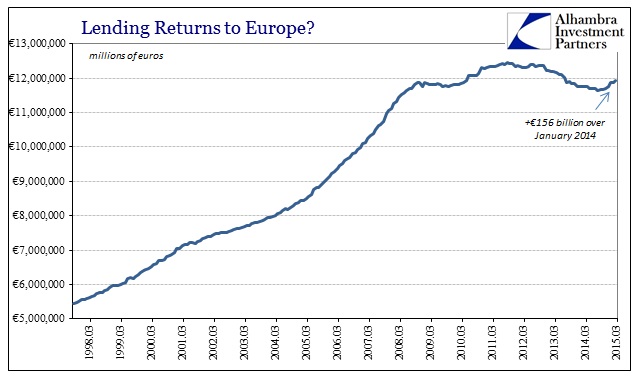

Bank lending has indeed increased lately, though only financial activity can easily and reasonably be related to QE/T-LTRO’s or the negative deposit rate. Since January 2014, lending in Europe is up €156 billion and 1.4% year-over-year.

While lending to households and non-financial corporations has been better of late, that does not appear to have much to do with what the ECB has had to do. If anything, lending in Europe to the private sector is tied more to inertia than anything monetary. Loans to households, for example, have been basically flat for the last three years, drifting and meandering around €5.2 trillion. That household lending has been impervious to everything the ECB has done in those three years is the only meaningful takeaway from the series, but that contradicts the heightening enthusiasm for QE.

That the year-over-year growth rate is positive isn’t newsworthy, as it was also slightly positive (and the positive was very slight for March, just +0.04%) from October 2012 through April 2013 – the last time the ECB was so sure of durable and robust recovery in Europe. Then, as now, that “upturn” in lending was attributed to the prowess and determined resolve of monetary policy in the form of LTRO’s, a colossal program itself that nobody seems to remember much anymore given how little of an impact it had (beyond financial distortions).

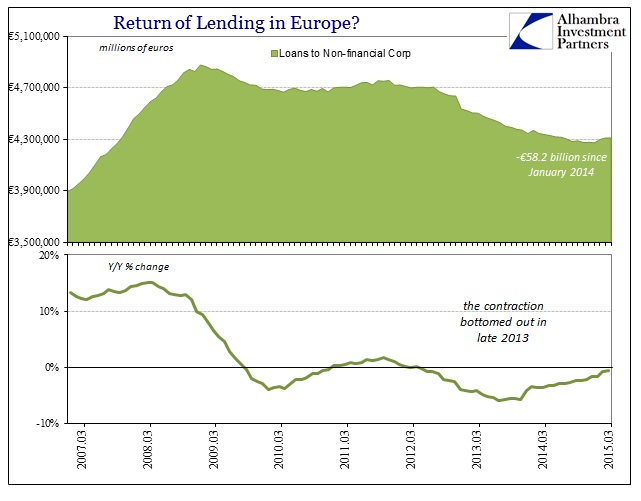

The track record of lending to businesses in Europe is slightly better, but again it is a matter of banks there bottoming out some time ago. In this case, the contraction in business lending was at its absolute bottom in late 2013.

If there is one segment of lending that has clearly a monetary origin (or at least the most reasonable attribution), it is the same old financial rejiggering that has become the hallmark of central bank monetary explosions since the panic. You would think, given all that the ECB is “giving away” in terms of pricing premiums and favorable liquidity, that lending in Europe to the actual private sector would likewise explode; instead all that has been accomplished is similar meandering while the financial sector is yet again sublimely thankful.

There are a couple of points to be made from this. First, even if lending to the private sector is attributable to something other than inertia it is not clear, especially from past history, that amounts to all that much in the real economy. Lending to both businesses and households perked up slightly from 2010 through early 2012 and it did nothing to prevent further and returned recession (Y/Y growth in lending to combined HH and NFC’s was as much as 3% in April 2011).

Second, even if we assume lending is a major component in recovery, there has to be consideration about what it took to get it (setting aside, again, whether lending was related to QE at all). In other words, the ECB has been desperate to gain a positive lending trend, undertaking any number of drastic steps to achieve it. There are side effects and collateral damage for having done them, and it is entirely possible that those negative effects are greater than any small or slight uptick in private lending. If the ECB had to kill the euro just to get some minor loan creation, loan creation may not have been worth the trouble.

In that sense, these monetary affairs become one of great extremes; the central bank determines to destroy the economic foundation for recovery just so that the recovery can have only a credit and financial basis. In light of where monetarism has come from, that is perfectly consistent with its internal history. The fact that it doesn’t work more than very short-term, artificial boosts is also perfectly consistent with external history.

I’m not sure either indication, loans or the PMI’s, amount to much, but I certainly understand why they are given such magnification. It is the reduction of actual expectations for economic success that accomplishes that. We are so far removed from actual economic growth, globally, that nobody much remembers it so that the smallest, minute possibilities, once nothing more than splitting hairs, are now the most important indications in the economic/financial landscape. The bi-polar nature of description is the essence of the ongoing and tragic loss of economic opportunity.

Stay In Touch