The Edmund Fitzgerald departed the Burlington Northern Railroad dock in Superior, Wisconsin on November 9, 1975, at about 2:20 in the afternoon. She was carrying a load of taconite pellets to Zug Island in the Detroit River, a rather routine run for this massive ore hauler on the Great Lakes. Only a few minutes after departing, the National Weather Service issued a gale warning for along the Edmund Fitzgerald’s scheduled route. By early in the morning on November 10, the ship was reporting winds of 52 knots and 10 foot waves.

While it was certainly rough seas, or lakes as it were, the Edmund Fitzgerald was the largest and probably most well-known of the Great Lakes haulers that moved huge quantities of raw materials coming out of the Midwest and Plains toward the East. For an ore shipper built in the 1950’s, she was pretty much state of the art and even boasted rather unusual amenities. That didn’t stop the ship from setting all sorts of records up and down the Great Lakes, becoming known as “Pride of the American Flag” and the “Titanic of the Great Lakes.”

That last nickname was meant of as high compliment in service rather than to convey any such perceptions about the potential for catastrophic mishap. Though the lakes were extremely hazardous, holding still a reputation for swallowing up ships and their men, by the late 1950’s and into the 1960’s modern equipment supposedly made the ship unsinkable. If there was such a thing possible running up and down that busy shipping corridor, the Edmund Fitzgerald was it.

So when the Fitzgerald’s captain, Ernest McSorley, radioed the Arthur Anderson in the middle of the afternoon on November 10, as that ship was trailing the Fitz by about 20 miles, it was somewhat of a shock that McSorley reported some damage to his vessel. He relayed to the Anderson that, “I have a fence rail laid down, two vents lost or damaged, and a list.” All of those were by themselves something to worry about, as even the fence rail indicated the possibility of structural damage in the hull itself (the fence was meant to be pulled taught by the “weight” of the ship under load, and if the rail came down something in the structure might have changed). Of course, the fact that the ship was listing and some vent covers were lost or missing indicated that the Fitzgerald was taking on water.

That did not normally produce the loss of any ship or vessel and was not even that unusual on the Great Lakes. These ships have enormous pumps and pumping capacity, but there is a limit, especially in rough seas, as to how long the ship could tolerate such huge imbalance and deviation from expected design performance. And, as is usual in these kinds of affairs, there were cumulative setbacks all through the rest of the trip.

At 4:10 pm, the Fitzgerald radioed the Anderson that it had lost both its navigation radars, asking the Anderson’s captain if he would help the Fitz navigate to Whitefish Bay. There was a radio beacon and light at Whitefish Point that McSorley was probably counting on in lieu of all his high-tech gadgetry. Unfortunately, as reported by a passing ocean-going ship, the Avafors, neither the beacon nor light were apparently working.

Sometime around 6 pm, McSorely reported to the Avafors, “I have a bad list, lost both radars, and am taking heavy seas over the deck.” It only got worse, as around 7 pm two waves buffeted the ship, riding right up over the deck 35 feet above the waterline. The bow of the ship would actually “sink” into each wave and then pop back up out of the water due to nothing but buoyancy. About 10 minutes later, the Anderson called the Fitzgerald, now trailing only about 10 miles behind, about some traffic in the area but that it wasn’t going to be a concern.

McSorley reported that, “we are holding our own.” It was clear that, despite all the damage, unworkable systems and even the weather and waves, the Edmund Fitzgerald’s captain was expecting continued operation and even better performance once they reached Whitefish Bay. It was the last time the ship was ever heard from, as the Anderson reported to the Coast Guard only ten minutes later that the Fitzgerald had disappeared from their radar. It did enter a small squall at that time, and it wasn’t unusual for the squall to obscure radar reports, but by 7:55 pm the Anderson was reporting that the Edmund Fitzgerald was still lost to radar and visual contact.

Nobody knows exactly what happened and the exact sequence that turned an “unsinkable” ship to the bottom of Lake Superior. The focus these past forty years has been on the boat’s listing and vent covers, taking on water, but there is no explanation as to why the pumps were insufficient. It has been speculated that maybe one or two of the cargo covers themselves came loose or even came fully off, and that with waves coming right up over the ship there was no way to equalize the amount of water going out and that which was flooding in. Whatever the case, the Fitz went down in one wave just as it had before, with the bow sinking into the wave’s stormy trough, and the entire ship just never came back up.

In many ways these kinds of disasters are a process. I think we tend to think of them along the lines of single events, which is where the Titanic comparison might be misleading in that respect. There was no “iceberg” for the Fitzgerald to impact and begin the catastrophic chain of events, but rather a sustained degradation to systemic capacity that, at some critical point, could no longer keep the ship afloat. It was such embedded deterioration that even the ship’s captain seemed fairly confident that ultimately it would turn out just another unsteady trip on Lake Superior. Instead, he suffered catastrophic failure after hours of nothing but attrition.

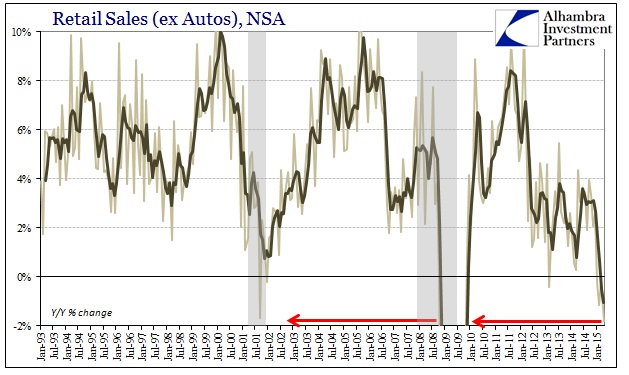

The equivalence of the Edmund Fitzgerald to the US economy is striking to me. Orthodox economics holds fast to the theory that recessions are, and can be, nothing but the work of an exogenous “shock” – the iceberg of the Titanic variety. The indications of consumer “demand” so far in 2015 not only suggest that is wrong but for the very reasons, from a systems perspective, that the Fitz sank – attrition.

For their part in this allegory, the FOMC even recognized the “rough seas” of the post-crisis era, making no shortage of excuses that they were dealt a very difficult hand to begin with (without ever admitting or even contemplating their own role in dealing that hand). But overall they believed that their monetary toolkit, especially QE, would propel the US economy through those swells and into the safety of the full recovery. In the past year, they and their parroting economists have been infused with even more confidence that the economy would pass through this barrier despite the continuous stream of indications that there were structural problems still unsolved, and that those structural problems were leading to the economy’s version of listing (namely the “mysterious” lack of income and wage growth).

Since monetary policy functions very much like the internal water pumps on the Fitzgerald, it seems appropriate to analyze them in the same manner as the nautical disaster. In other words, if the US economy is really about to head under the 2015 wave, and not buoy back up as it had briefly after the heavy wave in Q1 2014, then why hasn’t QE been effective at its design?

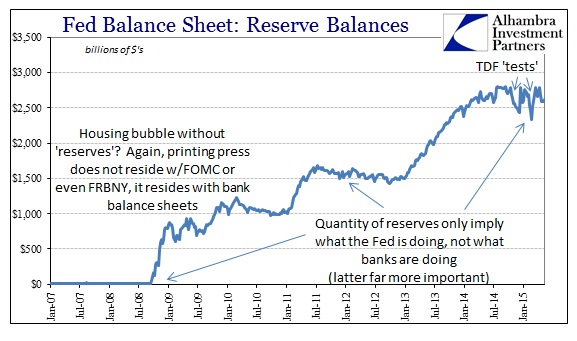

A clue to that lies in the state of monetary policy as it actually exists rather than what various people and even investors at this late stage think it does. There remains the stubborn idea that the Federal Reserve is and has been “printing money.” From that, it stands to some reason that the economy would be available for a positive injection of cash, the old idea of the equation of exchange. If you give enough people cash to spend, out of nowhere, then it will be spent and the rest of the economy is supposed to follow. It makes no difference in theory whether that comes as cash itself or cash from borrowing – more of either is supposed to create more demand for the sake of demand.

But even under QE that was never really the case. Buying bonds directly from primary dealers did absolutely nothing except increase the level of bank “reserves” (using scare quotes here, appropriately, because the reserve account at the Fed is nothing like what used to constitute actual bank reserves, though they are classified now as if they were). This is not to say that there were no effects of that effort, only that those effects were highly muted, mutable and indirectly captured by bank balance sheet constraints that were often unrelated even to liquidity in the immediate post-crisis period.

As even the Federal Reserve will tell you, the quantity of bank “reserves” only indicates what the Fed is doing and has no actual and direct bearing upon what banks, or the economy, might do. However, the FOMC does not at all mind if you think they hold such immense power so long as you don’t go too far in that unsupported belief. That is why the FOMC and its academic arm have been diligent in parrying criticisms about those expecting “runaway inflation” without ever admitting the full extent of reality in that effort.

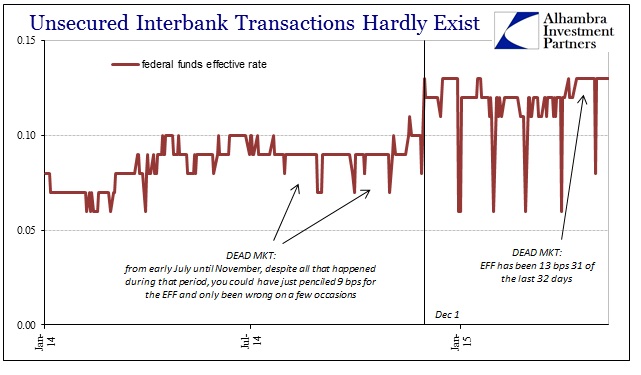

To which is added ZIRP, a factor that has been quite the topic of conversation since the middle of 2013. The FOMC exercises an interest rate target as its main lever of monetary influence, setting a range (or an exact interest rate prior to ZIRP) for the federal funds rate. This tool is at least one step in the realistic direction over QE, as the federal funds rate is derived from interbank activities among banks themselves. The premise is that banks drive the main mechanics in the interbank markets, the balance sheet factors that are crucial to all finance, but that the Fed can intervene in order to maintain its targets. The fallacy here is as those “reserves”, as essentially the Open Market Desk would undertake mini-QE’s (which are all just open market operations that change the level of cumulative “reserve” accounts) if the effective federal funds rate continued under its target.

So even in the interest rate target, the Fed is left with nothing but “reserves”, and in this case just the threat of “reserves” to control a major interest rate in order to reset and regulate systemically the price of the “risk-free” benchmarks (including and especially OIS). Prior to August 2007, that was enough as banks simply followed the target out of self-fulfilling expectations carried through arbitrage (both globally and amongst the survivorship basis in interbank payment mechanisms). However, in the post-crisis period there is another problem, one that has only grown over time, as the federal funds market itself is, quite frankly, dead.

What you see above in the effective rate is essentially what banks might offer of “cash” here if there was some actual demand for it. This is not a market in any meaningful way, a fact that the FOMC has acknowledged on many occasions. Most of those relate to suggestions and academic studies about repo markets which have taken over the relevant role of interbank determination. In fact, the Fed continues to be the only major central bank that does not employ its main monetary policy device through the repo market.

That leaves domestic monetary policy in the United States, of the world’s supposed reserve currency, as a process of fake reserves threatening highly indirect action in a market that nobody participates in. If that doesn’t sum up the economic predicament, than I doubt anything will ever do so.

For its part, the Fed does not care about all that. They are more concerned about signaling monetary policy to you and I and everyone in between. The actual pathology of how it is carried out in the end has become almost totally unimportant and irrelevant to how well the FOMC can “communicate” its intentions. In other words, never mind exactly how the Fed might do something like or around “money printing”, just as long as you assure yourself that something somewhere might happen as it is supposed to (as Janet Yellen continues to plead, stop worrying about the details and just accept her big picture socialism). I am not making this up, truth is far stranger than fiction, as the Fed will not move off its federal funds rate target to a more appropriate repo target because they don’t want to lose, in their minds, the ability to influence your behavior no matter how indirect, or, as in the case now, imaginary.

Monetary policy is all about psychology, to the point that the Federal Reserve itself will continue to use a non-existent interest rate in its actual “exit” (which I still doubt they will ever get to). In other words, there is no even “money printing” forward or in reverse as they increase rates, or keep them at zero; all that actually changes is a number published in the paper and talked about on the TV and internet. The full purpose is for you to get the message about what they intend for you to do without thinking about the operational impossibility of it taking place on their end; their main monetary policy rate is nothing about money, banking or anything in between but only a rate by which they think they will influence behavior and behavior alone.

Is it any wonder the economy is in danger of sinking toward catastrophic failure?

All that has been deployed as a counterforce to this continued attrition has been psychological, happy mumbo jumbo. The Fed stimulates absolutely nothing but the media’s descriptions of it and the various economists and their models that depend solely on them being successful in doing so. If recessions are emotional and irrational pessimism as the monetary textbooks believe, then QE and ZIRP are just right sort of “happy pills” to push emotions back to the “right” direction. The Fed can’t be bothered to hook its actual monetary programs into an actual market where actual finance is carried out, preferring instead the continuity of nothingness. The Fed continues its main line into the federal funds market despite the fact that nobody actually goes there, and hasn’t been there since 2008.

To finish in the analogy of the Edmund Fitzgerald, the water effecting a list upon the economic ship is real, the attrition, but the pumps that everyone thought were enough to correct all that are just imaginary creatures of a lot of happy talk and signals. It would be bad enough if they existed and just were not turned on, but, as the interest rate target in the dead federal funds market shows without ambiguity, the pumps don’t even exist at all.

But don’t get too pessimistic about it; their target for that dead market is still “stimulative” and “loose.”

Stay In Touch