Recognizing the danger of overdoing it on Greece today, I think there is another important and complimentary factor that the uncertainty about default there is revealing. In addition to the economic re-awakening about how nothing much has really changed with Greece, including its fiscal impediments that endure despite its default three years ago, the financial theme that has provided such buoyant exuberance since late July 2012 is in danger of being repealed.

Start with credit default swap prices on Greek debt, which includes the five-year maturity that was floated just last year. The “market” is predicting that the Greek government is 70-80% likely to default on its debt yet again, maybe as probable as 90% or more.

Given these dramatic stakes, the risk of a Greek default has gone way up. One way to measure that risk is by looking at the skyrocketing price of insurance policies that would pay out if Greek bonds go bust. The cost to insure Greek debt for one year against the risk of default has skyrocketed 456% since the start of the 2015, according to FactSet data.

These insurance-like contracts, known as credit default swaps, imply there is a 75% to 80% probability of Greece defaulting on its debt, according to Jigar Patel, a credit strategist at Barclays.

The probability of a Greek default soars to a whopping 95% for five-year CDS, Patel said.

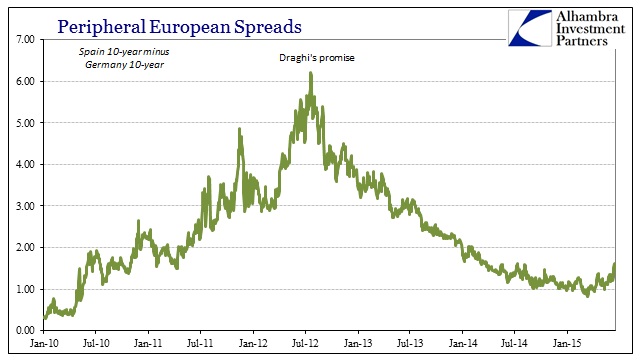

The entire point of Mario Draghi’s promise, on the financial end, was to convince the bond markets that sovereign debt in Europe would be treated as sovereign debt once again. That meant, in unspecified terms, that the ECB would never allow another loss event that would threaten the euro and the economic/monetary union (noose).

It has always (in the past few generations, under fiat) been a bedrock assumption of finance that sovereign debt was essentially risk-free. Governments, developed world anyway, possessed the ability to tax under almost any circumstances so if pressed on fiscal imbalance there would never be any real danger. What was left for banana republics was to be shut out of the bond markets after quite regular defaults by less “organized” sovereigns; no major nation would ever, it was assumed, suffer that great loss of borrowing capacity.

The Greek default in March 2012 certainly changed that idea, and so it was the ECB’s job as Mario Draghi saw it to corral Greece back into the fold of the “risk free.” After all, if Greece went so did the PIIGS and thus all might be undone. What Greece lacked prior to that point was as Keynesians and monetarists have embraced alike, namely that “full faith and credit” in terms of transforming mere sovereign obligations into “risk free” was not simply a fiscal matter, but also one of the central bank and the explicit fiat component of “printing” if need be. When Greece defaulted the first time, the ECB wasn’t yet committed to the orthodox “duty.”

So under the new commitment, post-July 2012, there would be no doubt that “full faith and credit” meant that in every literal fashion, from the euro through and through. That set off an enormous wave of sovereign purchases (largely, it seems, at the direct expense of actual lending that all this was supposed to aid) predicated on the idea that some “risk free” securities were trading, as in Greece, at less than half of par. That great burst was carried forward several years now on that exact premise; that prices would and could only go up because these were all “risk free” at huge discounts to the potential “value” under those terms. Getting Greece back into the bond market, so utterly soon after its default, was in this context a necessary step.

Greece heading toward another default is thus more than a little dangerous because it threatens to completely upset that paradigm – sovereign “risk free” is again being revealed quite otherwise. If banks throughout Europe and the rest of the world were only too happy to load up on what they thought they couldn’t lose on, where does that leave all this when that belief is not just challenged but disproved? It’s more than a little uncomfortable for bonds that were bought maybe in 2013 and early 2014, but downright dangerous for Spanish or Portuguese (or Greek) debt purchased more recently at insanely, historically-low yields.

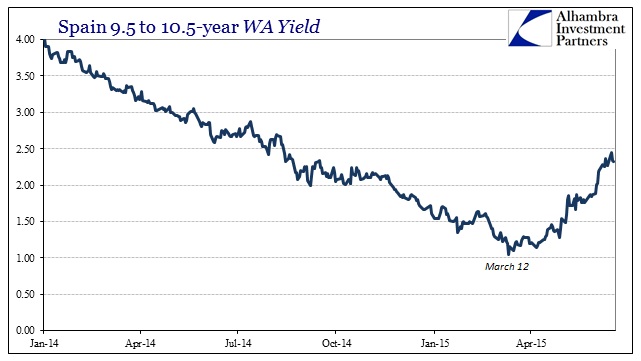

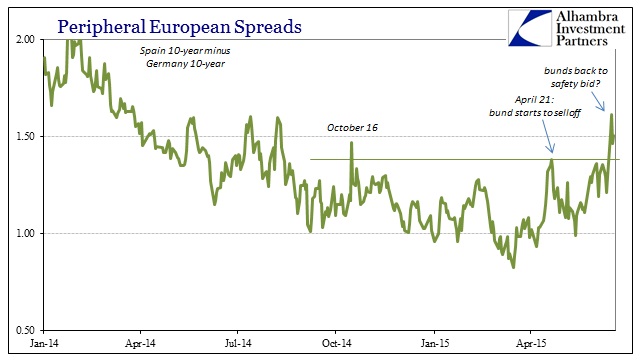

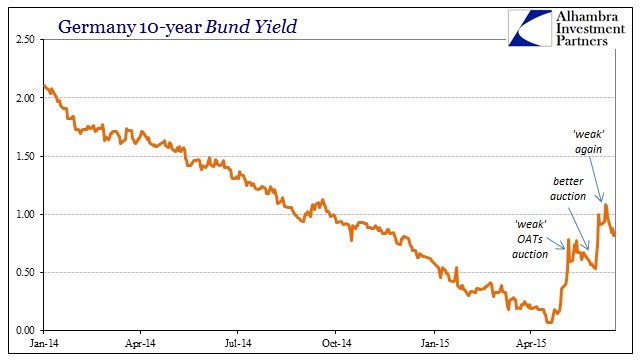

ELA usage in Greece didn’t rise until February 20 (week of) but most bond prices ignored that for a few weeks longer. That changed in mid-March as Greece propelled closer and closer to the same ledge that it was supposed to have been steered far away from by the ECB and default. Peripheral bonds moved and then the rest, especially Germany.

What European credit markets are displaying is not anything of QE or economic expectations, but rather a systemic, in progress resetting of risk perceptions due to the re-evaluation of “full faith and credit” as it became known July 2012 forward. In other words, what is being challenged isn’t necessarily the ECB’s commitment but whether that commitment, in the end, is actually meaningful beyond purely asset bubble behavior. Such reassurance in PIIGS bonds was merely a means to an end, but as Greece is in danger of taking, the “end” isn’t what everyone was expecting.

Bunds have been bid in the past week or so while peripherals have sold. That may be just a temporary divergence or it may be a return to the pre-July 2012 geographic divide. Whatever the case, contagion is a word that seems to be resurrecting especially as we know all too well how Europe’s banks cannot withstand much price disruption. If you recall the last round of “stress tests”, the ECB forecast the “adverse” scenario as where bond yields rose only to where they were in December 2013, forgetting all about 2011 and 2012.

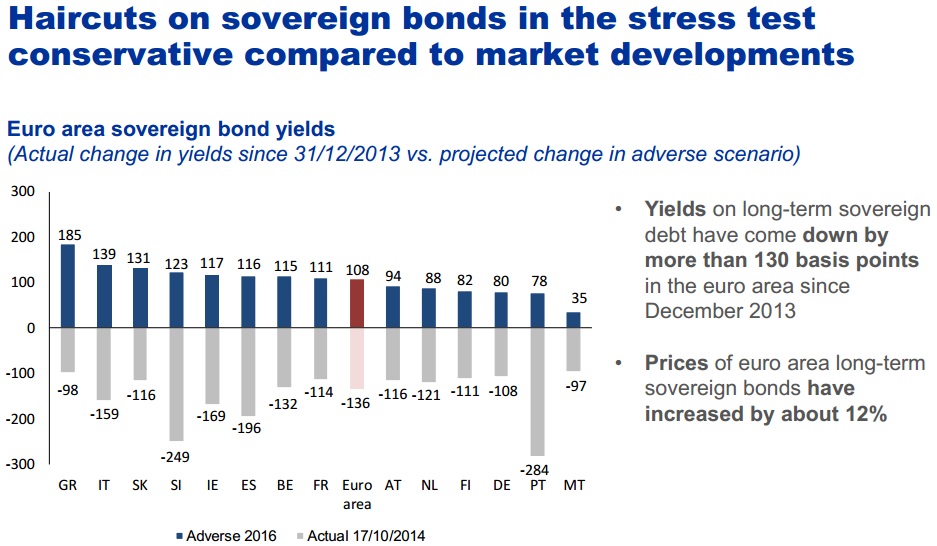

So the “adverse scenario” of sovereign bond yields leads to a situation where most simply return to where they were in December 2013 – not even December 2012, let alone the worst of the worst in July 2012. As is shown above taken directly from the ECB’s slide deck presentation for the stress test results, on average the “adverse 2016 scenario” is for sovereign yields to rise less than they have fallen since December 2013.

The pervasion of circular logic in that is par for the central bank course, in that the truly adverse scenario, a repeat of what actually happened in 2011 and 2012 is just a trivial concern because the ECB now operates the unspecified and unchallenged mantra of “do whatever it takes.” However, the truly adverse scenario is one where that “promise” loses all credibility as it combines directly with obvious impotence (and thus desperation) to actually accomplish anything in the real economy.

The “adverse” scenario for Spain was just +116 bps for 2016, not even 2015! Since March 12, the yield on the weighted-average 10-year has spiked 140 bps alone. The “adverse” scenario for Greece was, don’t laugh, +185 bps. So far of 2015, Greece has already blown through that threshold (the current 5-year was yielding 4.95% at issue last April and traded as low as 4.17% last July; as of yesterday it’s back at 19.66% with the 3-year at just shy of 30.0%); thus the ELA.

If banks in Europe were at all as fortified as is claimed, the modeled adverse scenario on a true test of potential price and bubble stress would have been multiples of the joke the ECB played on financial investors. And that is precisely the great danger here, that these “risk-free” securities are now like a heavy-gauge coiled spring, held down only by continued faith that somebody will play the white knight even though everything suggests that there is none or, worse, that it won’t actually matter in the end. You can start to appreciate why volatility in European credit has suddenly re-appeared.

Again, QE isn’t even much of an issue here except to denote, ultimately, the grand futility of monetarism once the bubble illusions wear off.

Stay In Touch