The proper use of statistics is, well, the proper use of statistics. While that is certainly a tautology it is also a valid criticism. The more “modern” we have become, the more the math is applied as if it were a substitute for general (and generous) scientific inquiry. Far too often, what is purported as such is nothing more than a specious arrangement of experimental factors given a regression equation that then is used to define sweeping generalizations for all of humanity.

While that last sentence may seem to be guilty of everything it proposes, the intrusiveness of statistics has only grown even though it fails at its own tenders. Behavioral economics, the term itself, is an attempt to blend distinctions in its own favor despite having so very little behind it. First and foremost, the idea that economists are anything like what most people think they are supposed to study: the economy rather than statistics. But in shifting to math a great deal removed from economy has left the discipline somehow overconfident yet at the same time perpetually confused.

For instance, did you know that a study of a few dozen paid grad students at a particular set of universities given a convoluted set of criteria about approving mortgage loans can lead to the conclusion that all human beings might have too much information now in order to make “rational decisions?”

Imagine that you are a loan officer at a bank reviewing the mortgage application of a recent college graduate with a stable, well-paying job and a solid credit history. The applicant seems qualified, but during the routine credit check you discover that for the last three months the applicant has not paid a $5,000 debt to his charge card account.

Do you approve or reject the mortgage application?

Group 2 saw the same paragraph with one crucial difference. Instead of learning the exact amount of the student’s debt, they were told there were conflicting reports and that the size of the debt was unclear. It was either $5,000 or $25,000. Participants could decide to approve or reject the applicant immediately, or they could delay their decision until more information was available, clarifying how much the student really owed. Not surprisingly, most Group 2 participants chose to wait until they knew the size of the debt.

Here’s where the study gets clever. The experimenters then revealed that the student’s debt was only $5,000. In other words, both groups ended up with the same exact information. Group 2 just had to go out of its way and seek it out.

The result? 71% of Group 1 participants rejected the applicant. But among Group 2 participants who asked for additional information? Only 21% rejected the applicant.

The conclusion:

The answer underscores a troubling blind spot in the way we make decisions. One that highlights the downside of having a sea of information available at our fingertips, and just might convince you to ditch your iPhone the next time you’re faced with an important choice.

Nonsense. We know nothing about the test subjects, particularly the homogeneity that is practically begging from flagging a small sample of only Princeton and Stanford students, so we are to generalize all of humanity against information? I can take the same results and turn them into a conclusion that using high-end university candidates is likely to end only in muddle for the most basic of tasks. This perversion of “statistics” has become overwhelming, particularly since most of those using the math don’t seem much familiar with its limitations – all that matters is “statistical significance” as if the words themselves apply, too, in sweeping generalizations.

If this were a limited phenomenon it would be more akin to harmless comedy, but alas it has been exploding. To wit:

Thirty students were each given groups of words and told to arrange the words into coherent sentences. One set of students were given words that might be associated with old people: Florida, bingo, wrinkle. . . . The other group wasn’t primed; they were given “neutral” words, like thirsty, clean, and private. None of the students was told the true purpose of the experiment. (Behavioral science usually requires researchers to deceive people to prove how easily people can be deceived.)

As students finished the task, a researcher used a hidden stopwatch to measure how quickly each walked from the lab. The ones who hadn’t been primed took an average of 7.23 seconds to walk down the hallway. The ones who had been primed with the aging words took 8.28 seconds. The second group walked slower, just like old people! The kids couldn’t help themselves.

The researchers barely disguised their feelings of triumph.

It could very well be that people in the second group had a different breakfast or that many were all forced to run 5 kilometers (university setting, after all) to the experiment’s location through a driving rain while those in the first group all caught the same bus for a leisurely arrival. But the “researchers” instead concluded that all people everywhere can be “primed” and thus “nudged” into one direction or another by the enlightened elite.

This has already taken beyond academic borders, as the same article quoted above (detailing the rather shoddy nature of these kinds of “studies”) illustrated what the Obama Administration is making use of this type of “information.” The first report of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Team jumped right in:

We can be relieved that the work of the team is much less consequential than it sounds. So far, according to the report, the team has made two big discoveries. First, reminding veterans, via email, about the benefits they’re entitled to increases the number of veterans applying for the benefits. Second, if you simplify complicated application forms for government financial aid—for college students and farmers, let’s say—the number of students and farmers who apply for financial aid will increase. “One behaviorally designed letter variant” increased the number of farmers asking for a microloan “from 0.09 to 0.11 percent.”

If that is entirely underwhelming, that is reduced in importance for the “other” grand assumption, that of precision. The worship of numbers has led toward an increasing assertion much like omniscience. Similarly from the UK a few years ago:

Prime Minister David Cameron of Britain recently promoted behavioral economics as a remedy for his country’s over-use of electricity, citing what he claimed were remarkable results from a study that reduced household electricity use by informing consumers of how their use compared to that of their neighbors.

Under closer scrutiny, however, tests of the program found that better information reduced energy use by a mere 1 percent to 2.5 percent — modest relative to the hopes being pinned on it.

Further, there is nothing about the “study” that actually models, as you might expect, any downside to the generalized interpretation of any statistical finding. In fact, this promoted use of a utility/energy scorecard was actually tested in Sacramento where the public utility started to actually give out frowny faces (authoritative omniscience would come, after all, in the Orwellian flavor of some kind of friendly emoji). Seriously:

A frowny face is not what most electric customers expect to see on their utility statements, but Greg Dyer got one.

He earned it, the utility said, by using a lot more energy than his neighbors.

“I have four daughters; none of my neighbors has that many children,” said Mr. Dyer, 49, a lawyer who lives in Sacramento. He wrote back to the utility and gave it his own rating: four frowny faces.

If there is anything missing from these attempts at distilling human behavior it is nuance; which is curious because nuance is the very stuff of human existence. If we were all truly robots, there would have been no progress. And in many ways, that is the real problem here, as these “economists” are attempting to define “optimal outcomes” for not just limited applications but for all human society (how’s that for sweeping). But in doing so they don’t understand, because MATH, tail risks are progress in life.

That, too, isn’t surprising, since regular economics has been in that business already for decades. As much as there might seem a distinction, both economics and behavioral economics share more than a common root and love for regression. They both lack the necessary humility that should not only accompany the task they set for themselves but should have, long before now, manifested in total appreciation for that which they clearly do not know. There seems no appreciation for understanding not just the limits of these extrapolations but of the process itself.

Undoubtedly, that insulation is a product of its setting – university studies and econometric models are entirely divorced from real observations if they so choose to be. Science is about observation (predictability and replicability) yet this modern turn toward statistics seems to have conflated that with nothing more than a mathematical equality. In other words, if the math is devoid of troubling singularities or unsolved non-linear functions, then it is taken as valid without closer examinations about whether or not that may be true.

Statistics, for all its potential benefits, requires some very distinct and potentially altering short cuts. You may, as a social scientist, arrive at numbers that look to be statistically significant but that is only a small part of the story. If you have to so narrow the construct of your experiment to arrive in that numerical promised land you have achieved very little apart from describing something much less than reality. A case in point:

So it was no wonder that Mr. Percy and Peter Petersen, the firm’s executive director, were visiting NORAD on October 5, 1960. They were joined by, among others, Thomas J. Watson, Jr., the President of the dominant computer firm IBM. At some point during their visit, the group was informed that equipment located at Thule Air Force Base in Greenland had flashed a Soviet launch warning, claiming 99.9% certainty that a nuclear salvo had been launched and picked up by the station’s radar.

The base immediately declared DefCon 1, a condition that would not be widely known until 1983’s Hollywood simulation of military stochastic simulations, WarGames. They called to Strategic Air Command and bombers were given high alert status, but no one could verify the attack was, in fact, real. Greenland’s Ballistic Missile Early Warning System was the only equipment declaring, essentially, nuclear war.

Since there was no nuclear war in October 1960 we can conclude that the statistical conclusion was rather inconclusive. What happened was nothing more than the moon rising; some engineer at some point in a complex process neglected to hardwire the moon’s profile, a fact of nature understood and predictable going back centuries and even millennia, into the computed “certainty” about the Soviet’s launching over Greenland and the North Pole. To the math as it was included in Thule’s warning system, such a basic mistake is a “tail event.”

It may seem like such a simple mistake on such an extremely important system, but the dangerous gaffe reveals something far too common of probability-based approaches. The idea of 99.9% certainty is not that at all, as such a mathematical number only refers to the narrow set of circumstances into which the parameters of the system have taken account. The system’s designers do everything in their power to try to ensure that in narrowing the sets of variables to be included, and then ranked by priority, that little escapes the math. What’s left after those exhaustive computations is believed by statistical “science” to be nothing but random errors – or, more precisely, errors that are thought and calculated to be as no more common in occurrence than random chance.

In the case of Thule’s statistical systems hardwired into its software, the moon was a “random error.” This is an especially easy case to visualize how statistic computations are not “science” in terms of predictability, as they are just as subjective as raw emotion. The fact that the system’s designers failed to account for the moon in just such a place as the detection field of view at the right time was bland oversight, but still subjective in its non-incorporation. There was nothing random about the moon.

Statistics is, reduced to its basic case, the inference of redefining reality by subjectively ignoring difficulties. Nowhere is that more apparent than economics, especially conventional econometrics. This is by practical necessity, as the millions upon millions of potential variables make it impossible to accurately model the actual economy; the covariance matrix alone would run into numbers unworkably large. So economists have collectively decided upon just a few important variables as if they explain the vast majority of variation observed in the real world and assume “the rest” left out of the equations is no better than randomness in performing actual fluctuations.

What seems to be left far behind is basic comprehension and appreciation. Economists talk the language of math at the expense of textured human existence. Take the case of assumed “inflation expectations.” Only recently have economists come to a suggestion (but nothing more) that expectations about future inflation might only have a partial impact on actual spending. It took several regressions to come up with the “realization” that perhaps actual income might have something to do with it:

In general, there are a number of reasons why the effects of inflation expectations on spending may be less economically significant and less robust than theory (and participants in some recent policy debates) might expect. While some of these reasons, such as nominal rate illusion, were discussed by Bachmann, Berg, and Sims (2012), a prime culprit not much discussed in the existing literature concerns income expectations. While the expected real opportunity cost of current consumption, figured in terms of foregone future consumption, falls as expected inflation rises regardless of future income, higher expected inflation may reduce expected real income unless income is fully and continuously indexed to inflation, thus putting a damper on consumption in both the present and the future.

Why is this even arguable? Because economists in the academic world of the Phillips Curve defined themselves (and continue to do so) too narrowly. In that binary view, only inflation and employment matter and it takes a whole lot of assumptions to fill in the gaping voids to maintain it.

The defenders of behavioral science like to say it is the study of “real people in real-life situations.” In fact, for the most part, it is the study of American college kids sitting in psych labs. And the participation of such subjects is complicated from the start: The undergrads agree to become experiment fodder because they are paid to do so or because they’re rewarded with course credit. Either way, they do what they do for personal gain of some kind, injecting a set of motivations into the lab that make generalizing even riskier.

Nothing recently has demonstrated that deficiency, the narrowing of reality to create a small laboratory circumstance, more than the failure of QE to produce what QE was supposed to produce. Economists even invented, essentially, an interest rate structure with which to analyze these “inflation” alterations. Called “term premiums”, Ben Bernanke was left dazed about why they had declined far more after QE than during it.

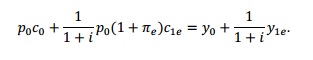

The answers are glaringly simple. Economists have detached from a real study of the real world in favor of a shared affinity for often needless complexity. Do we really need regression equations to define a household budget constraint (shown immediately above), to thus determine that actual and current income is a huge component of that? Common sense does not, but economists do. The worst thing that could have happened in this respect was public acceptance of anything like the ridiculous idea of the Great “Moderation.” By conventional account, that period “showed” it all worked; that Greenspan and his “rules-based” paradigm was really this kind of mathematical determination of monetary policy successfully guiding and forwarding the real economy.

But even to keep that narrative is to again reduce reality; to say there was “moderation” is to purposefully ignore the dot-com bubble or even the massive (and related, coincidental) monetary shift that took place in the 1990’s that Greenspan himself struggled to put in words. The Great Moderation was not so “real” as political invention.

Rather than redefine or even refine, the events of the 21st century have not reversed the malady. If anything, the whole thing has turned more so toward mathematics for salvation that it cannot deliver. “Quantitative” “easing” is but one example, though huge and universal now. And it is neither, in reality, truly quantitative except in the narrowest possible sense nor easing. At some point, there has to be a stand; enough with the numbers already.

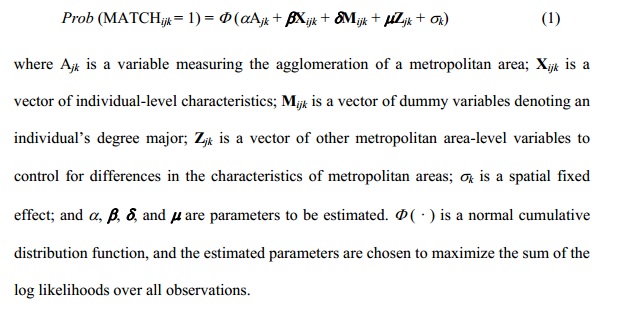

Ronald Coase said (wrote) it best all the way back in 1972. His admonishments were ignored, which only makes them all the more potent and stinging (and depressive) given where this has all turned out. I applied them in February 2014 in providing another useful marker on what economics truly is; namely a “study” that regressed variables to find that skilled workers find better job matching for their skills in urban environments. Yep, economists need this to state what is obvious to everyone:

It doesn’t have to devolve into a critique of far, far too much “book learnin’” versus “street smarts” but that is where we are. The pendulum has simply swung too far in too close infatuation with math combined with computer technology. There is nothing wrong with statistics itself, if only paired and conditioned by a healthy and great appreciation of its own limitations. It defines the current Bernanke-ism paradox – the more “they” quantify the world, the less they actually describe.

We may not quite be that far out in the open, yet, but I can see the Open Market Desk converted lest some common sense intercedes to trading “smiley faces” since QE is basically only that already. I have infinite confidence (pun intended) that some economist inside the Federal Reserve Board could even come up with a regression for the “right” amount of them, too; and that stocks would even rally upon the news. I am 99.9% certain it would do nothing toward raising anyone’s income, but that would be too many variables. This is the face of the modern technocracy, one devoid of appreciation for boundaries and limits even in the math by which they seek to control and wield. The world is not random or normally distributed, but they do make the calculations work. If only that was truly and broadly meaningful.

Stay In Touch