It is a myth of the modern age, particularly post-1930’s, that the American banking system needed a central bank in order to perform the function of currency “elasticity.” There were, of course, several severe bank panics that occurred in the decades before the Federal Reserve but they did not end with its imposition. The worst banking liquidation wave in history occurred with the relatively new Fed system in place, demonstrating conclusively that it is not the central apparatus that makes any difference. That point was further pressed starting August 2007.

The bank panic of 1907, for instance, was unusually confined. Typically, these kinds of currency problems (shortage) began in NYC and radiated outward. That was certainly the pattern starting in 1930 after the call market imploded and along with it the nation’s and a good part of the world’s payment system. The Knickerbocker panic two decades before, however, remained almost exclusively a Wall Street affair and, not coincidentally, was for once unaccompanied by severe depression.

The New York problem began with trust companies, a form of financial organization legally dissimilar from banks by intention. New York City banking organizations were distrustful of them and sought active exclusion from their membership. Banks since the earliest days of the republic had gathered together to form associations not out of social impulses but rather to function as private clearinghouses. They adhered to strict rules where the benefits were tremendous. As the Suffolk System in and around Boston in the earlier 1800’s, members found their bank notes more acceptable and liquid because of their standing within the clearing system.

Trusts were relatively new to the financial landscape and competed directly with established banks but free from reserve requirements. Thus, in NYC, the New York clearinghouse on June 1, 1904, implemented a 15% cash reserve for trust membership far above the 5% normally imposed on its members. The clearinghouse justified the regulation under caution and prudence given the legal distinctions. Almost all the trusts that had become members withdrew including Knickerbocker.

In the panic that began there in 1907, the trusts were then largely without liquidity recourse. In the Chicago clearinghouse association, by contrast, trusts remained part of the full structure. Those in Chicago continued to enjoy perhaps the greatest benefit of being a clearing member – quasi-currency. During periods of systemic and acute illiquidity, the clearinghouse would issue clearing certificates that functioned as internal, interbank currency. For any member being pressured by serious deposit or specie withdrawal, clearing certificates were useful in transacting normal business so that the bank run did not prove fatal (only harmful). These certificates or quasi-money performed the role of currency elasticity without any need for centralization and full-blown monetary monopoly.

The argument in favor of the Fed turned on what happened in New York rather than what didn’t, largely, in Chicago and thus the rest of the country. It is not an argument without any merit since the New York clearinghouse’s rejection and imposition of harsh requirements on trust businesses was the proximate cause for their lack of options in the runs of 1907. But that, however, does not necessarily argue for destroying the whole private system and starting again with central authority. Again, it bears repeating, the Fed’s track record isn’t enviable on this count, either, particularly of late.

Quasi-money in these kinds of formats is an ad hoc market-based response to what is really a dollar (or currency) shortage. In the form of clearinghouse certificates, this quasi-money attempts to bridge liquidity gaps by allowing essentially specialized interbank flow to move in specific fashion rather than through wider markets (experiencing disruption). In the case of the Chicago or New York clearing associations in the early 1900’s, not only were “strong” institutions available by which certificates could be issued, these firms also had intimate knowledge of the weaker firms where the certificates would flow. There was no problem of sorting “good” banks from “bad” banks as the clearinghouse knew which was which and therefore how to react relatively efficiently in response – in contrast to resorting to “flooding” markets with currency or liquidity as is standard today and taking so much distortions for it.

The appearance of quasi-money, then, is uniquely associated with illiquidity. There are other forms beside clearing certificates as we are finding out once again in 2016. The latest is Zimbabwe, the impoverished African nation with far too close experience to every kind of dreadful monetary degradation.

Zimbabwe will print its own version of the U.S. dollar, as an ailing economy fuels a severe cash shortage in the southern African nation. John Mangudya, Zimbabwe’s central bank governor, said Thursday the so-called bond notes will be backed by $200 million in support from the Africa Export-Import Bank, according to the Herald, a local government-owned newspaper.

“It is not an overnight process,” Mangudya told the Herald when asked what date the bond notes will be issued. “We are still working on a design which will be sent for printing outside the country. The notes will not be introduced immediately but probably within the next two months.”

Unlike Nigeria, Zimbabwe is not an oil exporter and thus being captured by a mercantile-driven dollar shortage. It is systemic and the country’s response is almost exactly like that of clearinghouse certificates. What the central bank is proposing is just that, as these notes will be backed (if the assurances of the government prove legitimate) by international institutions that can obtain them if needed in conversion.

While it is not at all surprising Zimbabwe is experiencing perhaps the most pressure in the dollar system that they would resort to such means, that also does not diminish the importance or significance of this sudden shift. As with the clearinghouses of early American banking, it is the weakest nodes in the network that first find themselves in need of unusual alternatives.

The issue in these kinds of cases almost always revolves around general instability. In Zimbabwe’s case, the country’s central bank has been trying to combat the dollar shortage with capital controls and encouragement of the South African rand in lieu of dollars. Unfortunately, the rand has also fallen victim to the “rising dollar” and thus leaves Zimbabwe’s people only further subject to monetary discord. Instability breeds only more instability, in response and again in “solutions.”

Reminiscent of 1930’s America, people there are reportedly lining up outside banks just to obtain enough dollar currency to pay for groceries and basic necessities.

Busisa Moyo, president of the Confederation of Zimbabwe Industries, said the notes printed by the central bank might relieve the cash shortage, but wouldn’t address the cause of the crisis. “What’s needed is to address the problem of excessive imports and the lack of foreign direct investment,” he said by phone.

Again, it’s the weakest links that are subjected to illiquidity first. There is a dollar shortage in the world and it only continues. Zimbabwe and other places have made that a physical phenomenon, using actual Federal Reserve Notes (and now quasi-dollar replacements), but it is no less apparent in the virtual world of the eurodollar. On that “side” of the global reserve currency, as noted of Japan today, the shortage is perhaps far greater as we find one central bank after another falling victim. I have not yet found any specific links between the shortage of dollars in Zimbabwe and the swaptions and cross-currency basis swap irregularities of Japan, but common sense dictates that a serious shortage of “dollars” would soon lead to a real shortage of dollars.

That is the big difference, however, between Zimbabwe’s experiment with quasi-money and Chicago clearinghouse certificates. In the former, it’s as if the dollar shortage were impacting the whole clearinghouse organization rather than specific institutions within it. In other words, Zimbabwe’s dollar problem is the dollar and not just Zimbabwe.

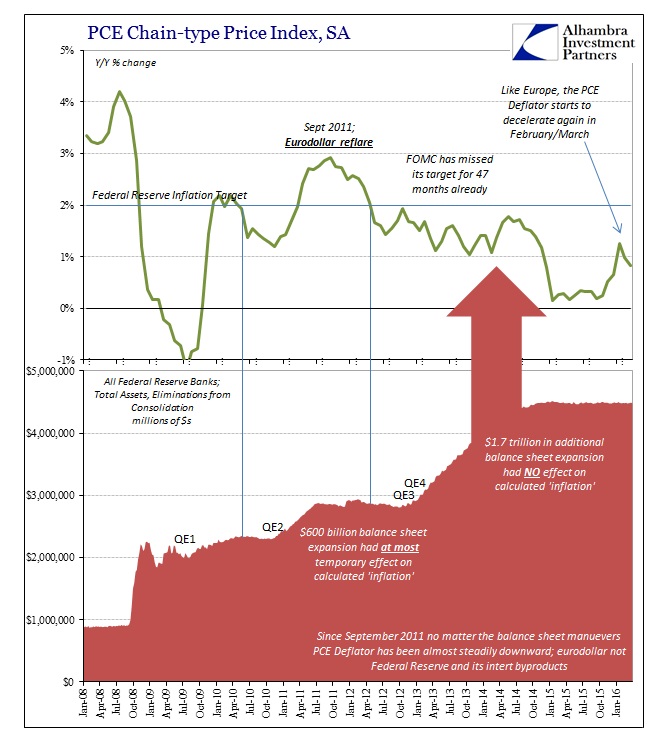

All of this sounds abundantly strange for a financial system supposedly bursting with dollars in the form of trillions of bank reserves. The Federal Reserve gave us its “flood” in four sustained applications, so by orthodox and traditional terms this is all just some big mystery of Zimbabwe being Zimbabwe; or Egypt being Egypt; Saudi Arabia being Saudi Arabia; Argentina being Argentina; Turkey being Turkey; Brazil being Brazil; Japan being Japan; China being China. There are big flaws in the centralized version of currency elasticity, too, starting with it being utterly dependent upon central bankers and their unique pairing of a self-imposed narrow view with unrestrained confidence in themselves. Given that framework, it isn’t surprising this dominant policy contradiction: they printed so many dollars that they seem to have just disappeared.

The Fed gave us so much “stimulus” that nobody in the “dollar” world (or dollar world) can find it. In reality we discover throughout the world, including the US, the Fed seems to have been a total non-factor. So much for modern elasticity.

Stay In Touch