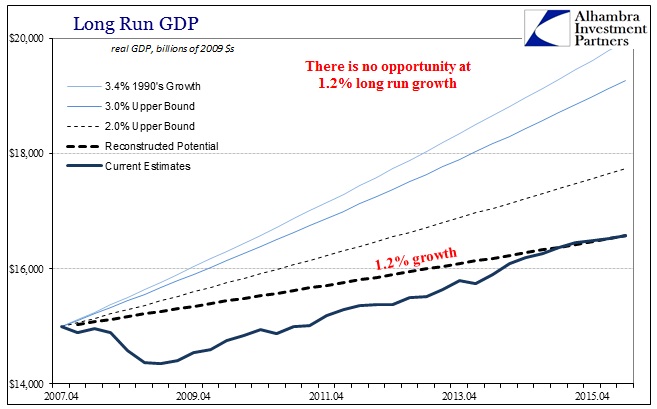

The end of the week finds the initial release of “flash” PMI readings across much of the world. In what will be surprising only to economists and policymakers, the commonality is “slowing.” It is never good to find universal deceleration, of course, but especially so in the second half of 2016. To begin with, whatever rebound there was in the middle of this year still hasn’t come close to erasing last year’s weakness. Therefore, if slowing is both real and picking up now, it suggests that economic activity never will.

In Europe, the Eurozone Composite PMI (combining manufacturing and services) slipped to 52.6, a 20-month low. The services component was noticeably weaker, down to 52.1, a 21-month low. Despite more QE and ECB expansion, there isn’t even the hint of acceleration just as there wasn’t last year when QE was first introduced. Instead, as Markit notes:

The end of the third quarter saw a further easing in the rate of eurozone economic expansion. September saw combined output across the manufacturing and service sectors rise at the slowest pace since January 2015.

Figuring prominently in the slowing is Germany. While manufacturing moved up to a 3-month high (though just 54.3), the services sector is alarmingly near 50. As usual, we have to take these PMI’s for what they are rather than expecting precision from them, meaning that Markit’s German services index cannot tell us the exact difference between expansion and contraction only that at most there are potentially some serious changes in momentum and activity toward the negative side.

Output growth at German private sector firms slowed further at the end of the third quarter. The Markit Flash Germany Composite Output Index fell from August’s 53.3 to 52.7 and therefore signalled [SIC] the weakest expansion in activity in almost one-and-a-half years. While service providers reported a near-stagnation of output during the month, manufacturers recorded ongoing solid growth.

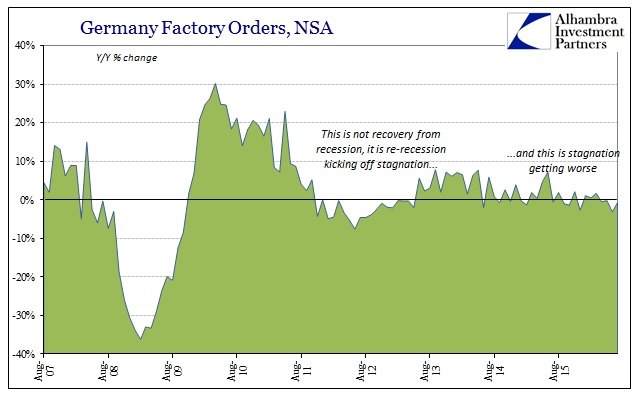

These figures corroborate somewhat the sudden and “unexpected” appearance of serious deceleration or weakness in Germany that manufacturing statistics suggested earlier this month. As I wrote a few weeks ago:

Growth had been sluggish for years but because it was less so in Germany it allowed the mainstream to continue to call the central European country the “powerhouse” or “engine” of Europe. Thus, if the “engine” already at near idle sputters, what would that mean for the rest of the Continent? At the very least it doesn’t reflect well on QE (again).

What Markit calls “ongoing solid growth” in manufacturing is misleading for its narrow comparison to everybody else in Europe, including German services if the PMI is valid at just 50.6. Such a low services index reading would seem to further suggest what slowing might mean for not just Germany (that it’s a serious problem).

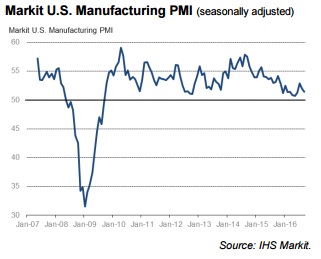

To complete the picture of slackening or further sluggishness, the Markit US Manufacturing PMI fell to just 51.4 in September. Like so many other accounts, the PMI had been (somewhat) rising through the spring only to rollover once summer started.

Softer rates of output and new business growth were the main factors weighing on the headline PMI during September. Moreover, the latest expansion of manufacturing production was the weakest for three months. Survey respondents suggested that relatively subdued economic conditions had acted as a brake on new order volumes, while there were also reports that the strong dollar had dampened export sales. Reflecting this, latest data signalled [SIC] that new work rose at the slowest pace since December 2015, while export orders dropped for the first time in four months.

“Subdued economic conditions” were supposed to be left behind with “global turmoil.” Instead, as the year wears on and moves toward autumn we find only more of the same, global, uneven grind lower and lower. It doesn’t matter what one central bank does or another doesn’t, the condition remains unaltered. That is the continued work of the “dollar.”

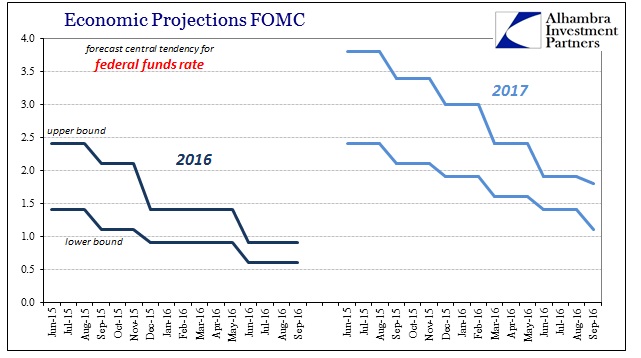

Keeping with that theme of money/UST rates:

U.S. government debt prices rose on Friday as investors digested the release of September manufacturing activity and comments from Fed speakers.

Again, it’s not about “stimulus” except that bond market has acknowledged that none of it is. These PMI’s, as with almost all economic accounts this year, continue to show there is no economic opportunity; at best, any acceleration is small by historical comparison and temporary. The word “transitory” has been applied by US officials to the wrong factors, showing again that their view is all upside down and backward because of how they wrongly view money. “Transitory” is more correctly the description of any purported strength.

Stay In Touch