It was announced yesterday that former New Jersey governor and one-time head of MF Global John Corzine won’t be allowed anywhere near clients in the futures business. Though a lifetime ban, the man is already 70 years old and the damage done. Perhaps there is some more comfort in the $5 million fine levied against him in addition to the banishment, as the CFTC went so far as to obtain a consent decree stipulating that he couldn’t use insurance proceeds to pay the penalty. This one is for once truly out-of-pocket.

I am not qualified to sit in judgement as to what constitutes appropriate punishment, only that in this case it appears the usual wrist slap wasn’t so usual. Maybe authorities finally realize that the injury wasn’t minor, though I doubt it. If anything, the heavier than normal penalties might have been applied in this case to get it to go away far out of any lingering popular imagination.

The issue always has been much more than misappropriated client funds. It speaks to the very nature of what banking has become, and it is nothing like banking. The saga of MF Global is the most candid if sordid example of finance as an operating principle in the monetary sector. Even cursory examination of the account reveals the twisted operating paradigm that passes for modern money and principles. That being the case, it would be no wonder authorities might be so interested in having it go away, trying hard, it appears, to claim a scalp this time in order that it will do so.

The full story of MF Global is a complex and lengthy one, so I will only recap briefly here some of what I have written before (many others have done far better tugging at all the inconsistent strands). This, for example, from March 2014 is as good a starting point as any:

There is a whole lot of legal opinion incorporated in the MF Global case, and not an insignificant amount of very cutting and even reasonable conspiracy theory. From the outset, there is a distinction between futures markets and actual property, though that kind of transaction straddles both. Under the CFTC rules and procedures, the futures market is supposed to operate like a physical equivalent, but anyone participating there better know that this is at best a hybrid. This is not to say that those unfortunate investors that were tied up in the unseemly mess deserved their fate, far from it, only that there is a vital distinction here where a window was open to change property into finance. In that disaster we see exactly the change in character where banks have undertaken a leading position in the order of arrangements. To think that this has no wider and downstream effects in the real economy is to be blind.

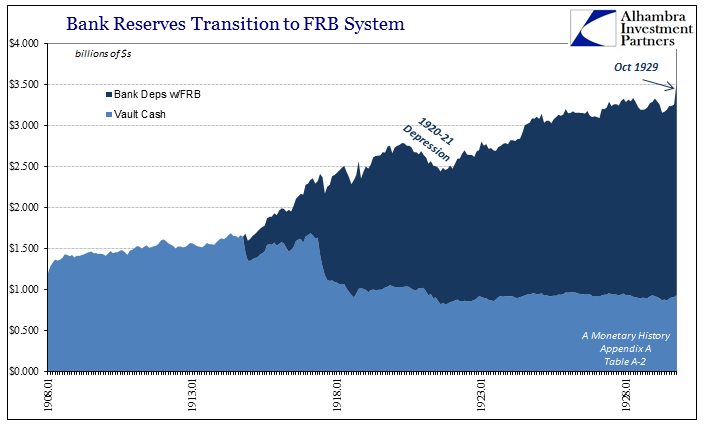

It really is quite simple, leading us back to where TBTF came from. In finance, banks are the center; in traditional money, they are tangential, at best custodians. Inevitably, however, someone will bring up the Great Depression as if a refutation, where traditional money was supposedly no barrier to grand and catastrophic disaster. To that I will always reply with two words, those signifying the exact time where all this started to move: “borrowed reserves.”

It’s simply not enough to realize that there is no difference between a $20 bill and a $1 dollar bill except the symbols and numbers printed on them by the authorized government agents. The number of people left among us who lived under a regime where that actually mattered is exceedingly small now and will (unfortunately) disappear into history very shortly. In very simple terms, the more fungible money becomes, the more central role will be taken by banks.

Ironically, the introduction of technology allowed the exchange of ledger balances, transactions that needed no physical settlement, thus rendering clearing even more mechanical. But introducing widespread “ledger money” meant also a break in the limitations supplied by money as physical property. If money is solely property, the bank can never be anything more than a property agent providing a clearing and custodial service, a systemically minor task. However, breaking the physical limitation was the transformation that made the desires toward potentially unlimited finance possible – what was transformed was the balance between banks operating in finance and those operating as custodians.

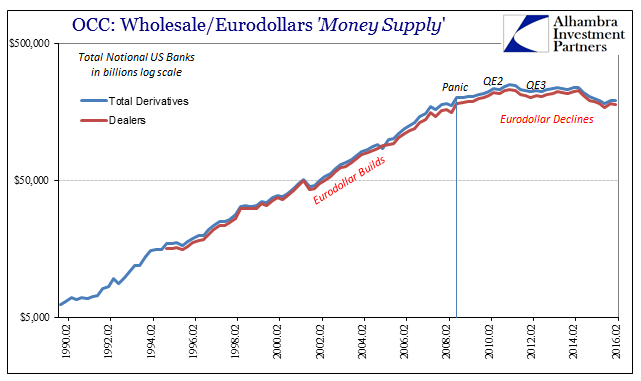

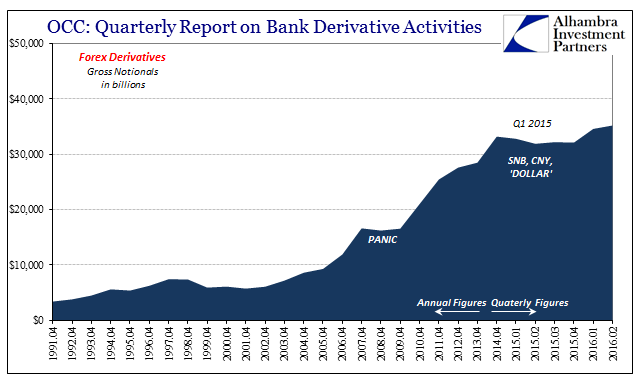

Once money is transformed into something intangible, the bank is also transformed in both function and situation – the balance between finance and property custodian was obliterated, as banks became largely all the former at the expense of the latter. We saw exactly this process in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, as eurodollars took on an increasing role in global trade settlement – and the only realistic means of settlement after 1971. But in the eurodollar market, ledger money is the sole and predicate resource foundation, meaning banks are not clearing via physical transactions, but rather extending credit and providing “risk transformations.” The bank moves from the background to the forefront.

This is, of course, not strictly a monetary issue; it is exceedingly an economic one, too. Under financialism, if banks founder then the economy will follow. And if the “best and brightest” of central bankers can’t fix the banks, then after almost a decade they might even give up trying and leave us all stuck in the depression of still purely financialized hell.

This needs to be one of the key elements of reform: to move banks back into the background, but not the shadows from where these modern versions suddenly leapt forward decades ago, and keep them there. Close study and recollection of MF Global even after so many years will aid greatly in understanding why. You need not rely on my word for it, as the bankruptcy and contentious nature of its fall put it all, for once, right out there in the open.

Stay In Touch