Europe has not been left out of the “reflation” trend, with some seemingly good news having been reported recently. Inflation has ticked up to the highest in three years. The Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) for the Euro Area was 1.1% in December 2016, year-over-year, the first measure above 1% since September 2013. It is easy to see oil prices in that acceleration, but economists are quick to claim monetary influence.

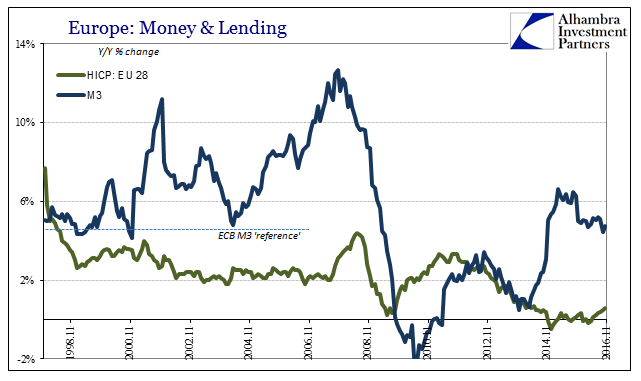

The ECB going back to its earliest days in operation as a central bank for the whole of Europe has pronounced monetary stability as one of the two “pillars” (the other being economic analysis) to achieve price stability. As such, the central bank used 4.5% money growth not so much as a target but as a reference point for defining what is, or at least was, “normal.” That standard for comparison was applied as broadly as they could manage, using Europe’s M3 for the relevant conception of not money supply but “demand.”

The best post-crisis that was managed up to the end of 2012 was 3.4% M3 growth. Starting toward the end of 2014, however, M3 accelerated and since the end of that year money growth has been stable at around 5%. Given these two outcomes, inflation and money, on the surface it seems reasonable to assume one created the other. The buildup and stabilization of seemingly solid money growth (due to QE and other ECB programs) appears consistent with expected inflation behavior, at least when given enough time.

If European monetary fundamentals are responsible for the upward turn in inflation, it would be the first time the relationship has held in more than a decade. That extended observation is not something that can be simply set aside, as it relates how there is every reason to suspect there is no (or very little) relationship between M3 and the HICP version (or others) of inflation.

Throughout the middle 2000’s there was clearly none, as money growth was often wildly enthusiastic while HICP inflation was almost perfectly steady. The lack of correlation even forced the ECB to rethink its entire monetary “pillar”, the central bank holding a conference in late 2006 ostensibly to do just that. German newspaper Handelsblatt reported at the time:

The ECB’s staff presented a paper in which the staff presented some hitherto unpublished information about the development of monetary analysis within the ECB. The paper contained a comparison of the accuracy, bias and volatility of inflation forecasts derived from monetary and other indicators…They stressed that the ECB had found money demand not to be stable and had consequently downgraded the role of money demand functions in its analysis.

It wasn’t until 2007 and 2008 that the HICP in Europe finally “noticed” the heavy money growth, in M3 then speeding at more than 10% per year. That suggested then mostly oil prices, which were undeniable in their influence. The past few years, where M3 growth is once more well above inflation, suggests all over again that there is more to the European monetary landscape.

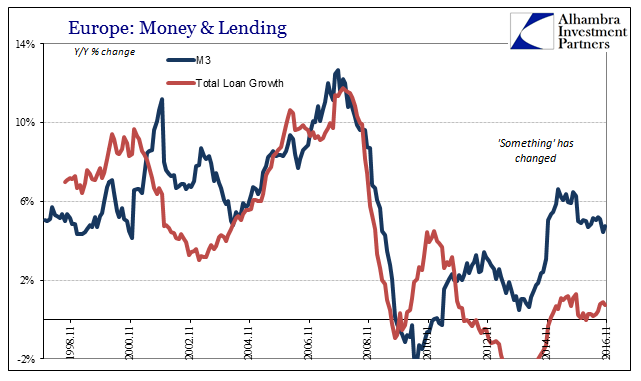

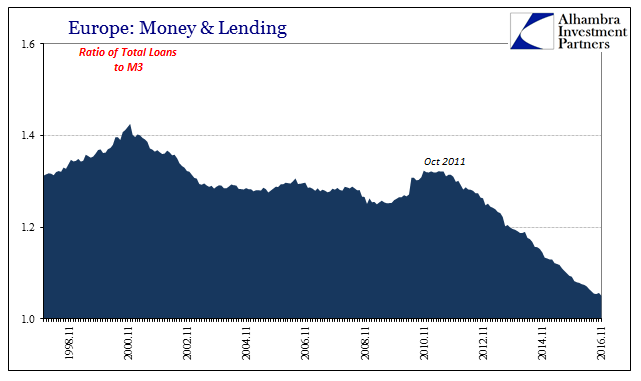

For one, where inflation was divorced from M3 total lending was not – but is now. Up until 2010, there was a very well defined correlation between monetary growth and lending in Europe. This was the presumed basis of monetary “demand” even though it didn’t result in creating so much consumer inflation.

That relationship has broken down especially in the years after 2011. There is perhaps a general adherence in overall pattern, but lending clearly responds less to money growth now as compared to the pre-crisis period. In other words, money growth may appear to be “normal” the past few years, but lending in Europe remains curiously stagnant. What it suggests, as is quite clear on the chart above, is that there is again a whole lot of “missing money”, just as there was in the 1970’s. This time, however, what may be missing is a drag, a global one.

For the first part, if M3 and lending growth were almost perfectly correlated up to 2008, but inflation was not, it immediately proposes the question as to where all the credit growth ended up. Economics expects money to become credit to become inflation, but if 6%+ money and credit would not so much as disturb inflation there is clearly something missing. It’s not as if the European economy had, in real terms, undergone such a boom of unparalleled fashion; far from it, Europe in the middle 2000’s was as the US had experienced mostly of lackluster expansion at best.

Money growth created credit growth that didn’t spark consumer prices or overly robust output, leaving few other places it could have disappeared into. One such wide open space that had the capacity to have absorbed massive financial input was the shadow credit system, one that was global in reach. The eurodollar system was once referred to as “hub and spoke”, meaning that banks in whatever local jurisdiction (including Europe) would raise funds in local currencies or capacities and then transform them into global assets via shadow conduits including FX (“dollars”).

If there was massive monetary growth in Europe combined with massive credit growth that didn’t seem to in any way affect Europe, it isn’t difficult to find answer in Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke’s “global savings glut” that was neither savings nor a glut, but was very much global.

It is tragically ironic that Greenspan, in particular, would find the theory plausible, as it was he more than perhaps any other global monetary official who throughout the 1990’s had decried the breakdown of these very correlations. I continuously refer to his “irrational exuberance” speech in 1996 for this very reason, for if you actually understand what he said (which was not really about the stock market) it was essentially a prediction of what we would take place in Europe (and elsewhere) in the decades following his words.

At different times in our history a varying set of simple indicators seemed successfully to summarize the state of monetary policy and its relationship to the economy. Thus, during the decades of the 1970s and 1980s, trends in money supply, first M1, then M2, were useful guides. We could convey the thrust of our policy with money supply targets, though we felt free to deviate from those targets for good reason…

Unfortunately, money supply trends veered off path several years ago as a useful summary of the overall economy. Thus, to keep the Congress informed on what we are doing, we have been required to explain the full complexity of the substance of our deliberations, and how we see economic relationships and evolving trends.

The European experience in the 2000’s was still more evidence to Greenspan’s warning (and it was a warning, though it just wasn’t enough in his own mind to overcome the hysteria of the dot-com era to which he also fell victim, believing eventually in his own legend above such rational observation). Using the broadest monetary measure available, European money was still “missing” several characteristics or measurements in order to fully make sense of the decade of the 2000’s. Broad money M3 still wasn’t nearly broad enough, as there was much more going on.

We can arrive at no other conclusion in the post-crisis period, as well. On this side, however, the monetary breakdown is more complete, particularly after the re-crisis that so closely followed the big one.

Money growth after the events in 2011 has been utterly divorced from lending, therefore economy, therefore inflation. If we take the money “supply” figures apart by type, we see that the same rejection holds for deposits where often ECB policy ends up more directly.

The only legitimate observation pertaining to monetary estimates is found in non-M2 M3. The definition of the M’s often deviate somewhat from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, but for the most part M2 and M1 are traditional concepts of currency plus different forms of deposits (near money). What is left out in M3, the parts not included in M2 or M1, are usually the wholesale stuff like repos and money market funds. In Europe, these are called “marketable instruments” which is, for once, an appropriate description.

Unlike the “dollar” system, there is much less to be hidden by euroeuro’s (offshore currency and parallel funding of risk and currency transformations) so that the European monetary system gives us a more complete picture in euros. In terms of just “marketable instruments”, non-M2 M3, the lack of lending in Europe post-crisis starts to make a great deal of sense; as does, unsurprisingly, the huge surge in lending prior to the crisis.

At the absolute peak in December 2008, non-M2 M3 totaled €1.36 trillion, which was very much the wholesale surge witnessed in all the various dimensions across currencies (the rising trend had ended, as it had in those other dimensions, at the end of 2007). As of November 2016, this monetary component was just €673 billion, less than half of the prior total. And though it is no longer falling anymore, non-M2 M3 like overall lending is more stagnant than growing. As much as Economics makes out all these various monetary components to be close substitutes, they are not as there is an especially big difference among and into these wholesale spaces.

Though deposit growth has been far steadier, which you can attribute to QE if you feel compelled to, it has been as a transformation, too.

Low and zero money rates have induced banks deposits to become more the shortest terms than at any other time; now more than 63% overnight, which in the M’s has the effect of reducing or slowing M2 while M1 rises sharply (a QE/LTRO effect). While deposits are in the aggregate only created by banks, and thus in the aggregate there is no distinction between term and overnight deposits, to individual institutions they are a far less stable funding source than time (term) deposits. Any bank that finds itself with such a high and rising proportion of overnight liabilities even in deposit form is going to be far more cognizant of, and even dependent upon, “marketable” alternatives – the wholesale world of non-M2 M3.

The combined transformation of deposits into the shortest terms plus the breakdown in wholesale volumes and capacity would certainly be one primary reason why banks would be shy about lending, preferring instead to “invest” more so in the most liquid and “safe” securities like sovereign debt. This is not the only reason, of course, as there are those other more hidden monetary dimensions yet to consider (FX, derivatives, regulations) as well as the still-lacking landscape in terms of opportunity and economic risk.

With Europe (and the rest of the world) still “missing” so much money, it is difficult to attribute the rise in HICP to much more than oil prices and the lack of further erosion in its economic fundamentals. M3, as it has since just about the time the ECB was founded, is at best incomplete. But in the “reflation” climate that starts 2017, there is very little nuance or desire to more thoroughly review the global monetary condition of the last twenty years since Greenspan’s warning. Deposits don’t matter so much, at least not in the way they are “supposed” to, meaning the relevant money condition(s) is (are) clearly somewhere else further away from central banks and monetary policies.

Stay In Touch