In September 2016, Wells Fargo fired 5,300 employees. These sorts of mass layoffs have become common in banking throughout the post-crisis era, especially those years of the “rising dollar.” This was different, however, as Wells was not cutting back in capacity but dealing with the aftermath of being far too aggressive. These employees were found to have opened secret and unauthorized customer accounts to charge fees in order to meet sales targets and therefore bonuses.

An internal investigation suggested as many as 1.5 million deposit accounts were created for this, as were 565,443 credit card applications. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) issued Wells a record $185 million in fines and ordered $5 million in restitution. In a memo to employees, the bank, as they all do, stood by its commitment to customers.

At Wells Fargo, when we make mistakes, we are open about it, we take responsibility, and we take action.

OK. Yesterday, the New York Times reported that once more Wells Fargo might have been doing wrong, this time having charged as many as 800,000 auto loan customers for auto insurance they didn’t need or want.

The expense of the unneeded insurance, which covered collision damage, pushed roughly 274,000 Wells Fargo customers into delinquency and resulted in almost 25,000 wrongful vehicle repossessions, according to the 60-page report, which was obtained by The New York Times.

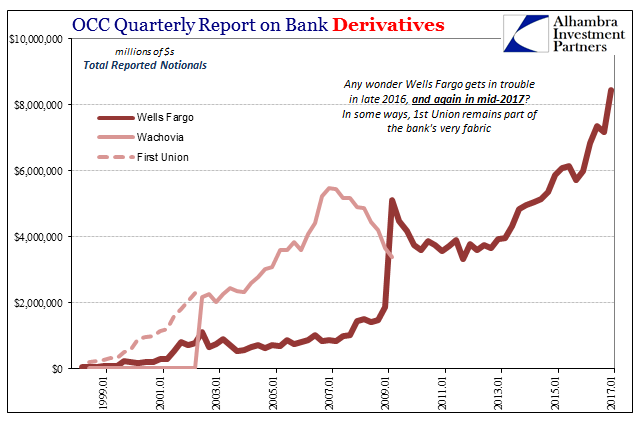

Wells Fargo used to be the sleepy behemoth providing mortgages far back from the front pages where firms like Citi (largest bailout in US history), Deutsche Bank, Bear Stearns, and Lehman were regular visitors. But that wasn’t really true, as the history of Wells Fargo in the post-crisis era is the absorbed history of firms like First Union and Wachovia.

No one should be surprised by the uncovered wrongdoing over the past year based on one single chart:

While other banks have been cutting back often severely in their derivative books, Wells Fargo has bucked the trend and charged ahead. As I wrote in May:

It’s what makes the clear inflection in 2008, really August 9, 2007, such a monumental event. Practically all at once these dealers began to finally see and appreciate all these contradictions, for they are nothing other than that. A guy named Fast Eddie running one of the world’s largest derivative dealers? Perfectly consistent, however, as an apt description of an age and conditions that just no longer apply.

Except for Wells Fargo. Notice the inflection in the bank’s derivative activities, the middle of 2013 when the “taper tantrum” at the time nearly collapsed Wells’ bread and butter mortgage refi business. Rather than face shrinking as almost all the others have done, the bank embraced risk and, obviously, the aggressive behavior that goes with it.

It says something fundamental about banking in this day and age, illustrating again the transposed nature of the paradigm post-2008. To generate even modest returns requires ridiculous risk, including, apparently, illegal activities. It’s not due to regulations but conditions. Most of the rest of the banks chose to shrink rather than go beyond certain boundaries.

On the whole, that is the behavior we would want in banks (the others, not Wells). But the monetary system, this credit-based global currency regime, remains in place rather than ten years ago having been removed and replaced. Prudent bank behavior is thus imprudent monetary behavior, an entanglement that is at the heart of the global economic predicament.

In that way, Wells Fargo performs something of a further service by demonstrating once again that the path out of this mess is not to go back. We want banks to be boring, not criminal. But we need to extract money creation from them so that they can continue to shrink if necessary while not also reducing the capacity of the monetary system as they do. The answer is radical reform, not dreams of 2005.

Stay In Touch