If “reflation” was born last year in Japan, and I think it was, it was surely given its most tangible dimensions in China. The idea that the Bank of Japan was going to do something magnificent was perhaps always a longshot, but enough given the times for people to hope (sentiment) they might try (helicopter). The Chinese, however, have been relatively more pragmatic. Authorities began 2016 with an actual rather than imagined “stimulus” injection that by around mid-year appeared to be paying off.

The backbone of China’s internal economy has been its ghost cities, but not as they may be ghost towns now, rather in how little time they might take to fill up. If the lag was relatively small because of restored growth, more would be needed and the Chinese building economy rolling ever onward.

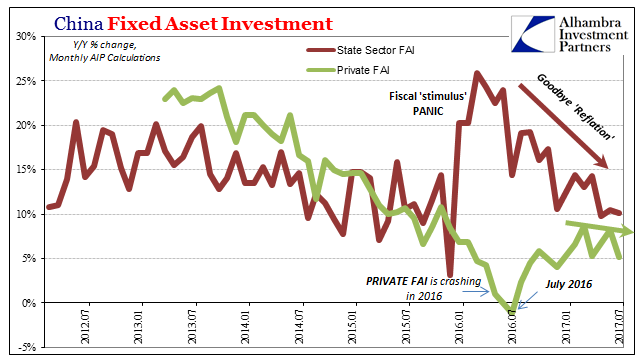

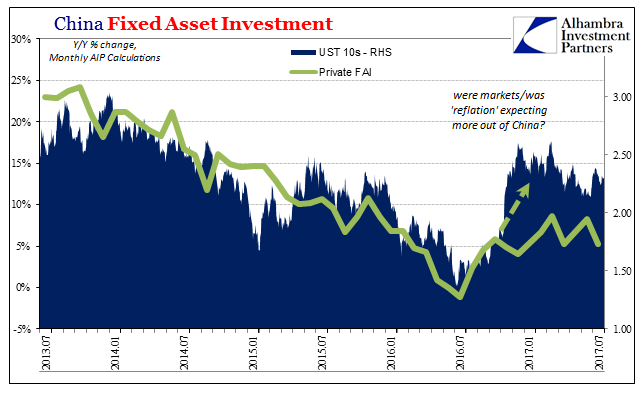

“Reflationary” prices were often Chinese prices of just that perceived process. The perceptions of a possible “hard landing” due to the global downturn of the “rising dollar” meant for many of them little additional construction and all that would go with it. The spark of hope from “reflation” coincided with the inflection in Chinese construction. Private Fixed Asset Investment (FAI), which had actually contracted by mid-year 2016, and what we are really talking about with ghost cities, turned positive just in time for the major shift in sentiment.

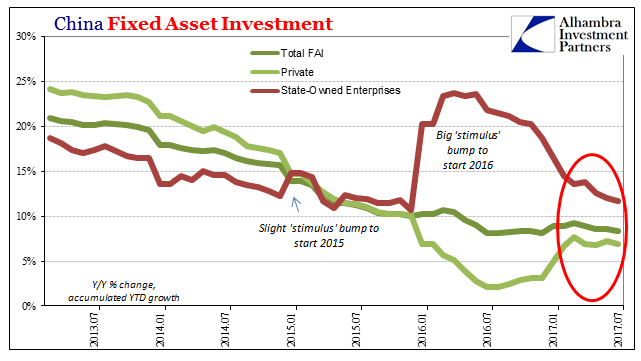

It increasingly appears as if officials in China believed the narrative, too. Around the time the private side was turning positive on FAI, State-owned FAI (the outlet for government fiscal “stimulus”) began to be incrementally scaled back. If at a lag, authorities didn’t want too much fiscal imbalance if private “reflation” was taking hold.

But the private side never really rebounded. In FAI terms, growth has been restored but at an incredibly low rate this year so as to be practically indistinguishable from the troubling levels of last year. Construction stopped contracting but no better than that.

It seems wholly incompatible with “reflation” as an ideal. I have little doubt that these various markets were expecting more; a lot more. As such, the further this year progresses without significant acceleration especially in FAI, the less there can be to a “reflation” emphasis, even belief.

Private FAI in China has not only failed to hasten in recovery, it has actually slowed somewhat from early in the year. The latest estimates from China’s National Bureau of Statistics show an accumulated growth rate of just 6.9% in July 2017, meaning that Private FAI in just July was only 5.2% more than in July 2016 at the trough. State-owned FAI has stabilized the past few months at around a 10% rate of expansion.

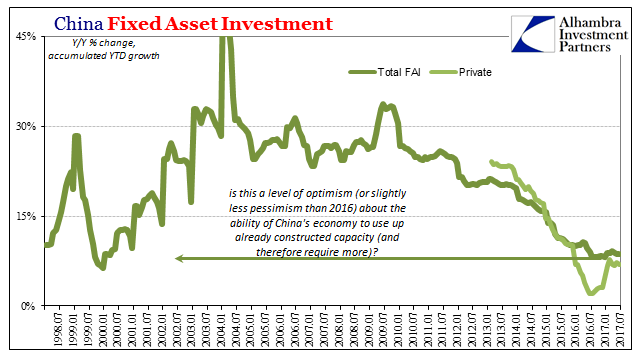

That means Total FAI, Private plus State-owned plus a few remainders, continues in 2017 at a growth rate less than a third of what it was and was likely expected as late as 2012. “Reflation” can pick up no further upside because the one part most tangible in all of it has like everything else only disappointed this year.

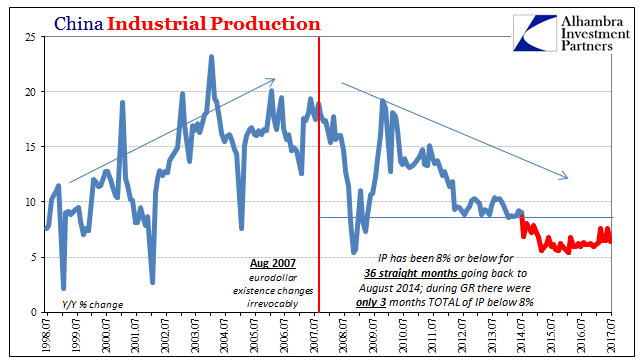

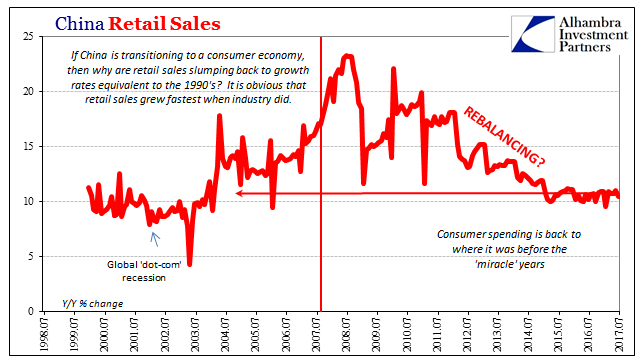

The others of China’s big 3 statistics, Industrial Production and Retail Sales, were similarly disheartening in July. IP grew 6.4% year-over-year, about the same pace as all of 2015-16 when people were thinking outright recession in China. And despite all rhetoric about rebalancing the Chinese economy toward consumers and services, retail sales were stuck yet again less than 11% last month, rising 10.4%, which is less than the average growth rate during this curious sideways trend for these two statistics.

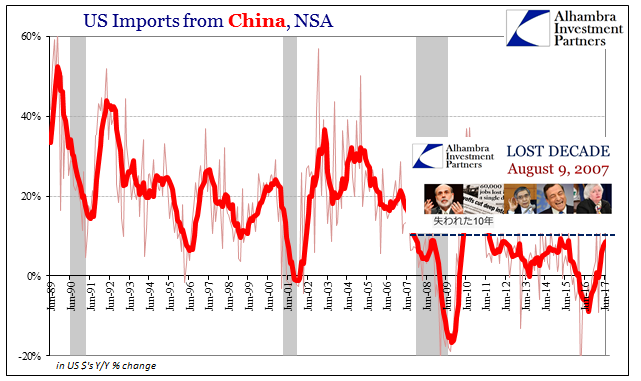

Though it isn’t quite dead yet, this latest “reflation” from the very beginning deserved the quotation marks in the same way as those that came before it. Pinning any hopes on the Bank of Japan to get the smallest thing right is always a mistake, let alone for them to be daring, imaginative, and ultimately effective in broad fashion. There may have been a more realistic shot for it from the Chinese angle, but only so far as something materially changing over there.

In other words, most if not all mainstream analysis about China has not been honest. The only thing that really changed was the level and channel of government intervention; prior to the start of 2016, Chinese authorities were content to ride out the “rising dollar” as if it wouldn’t lead anywhere too dangerous. When it did, they responded as officials always do (as if past failed programs of similar natures had never happened).

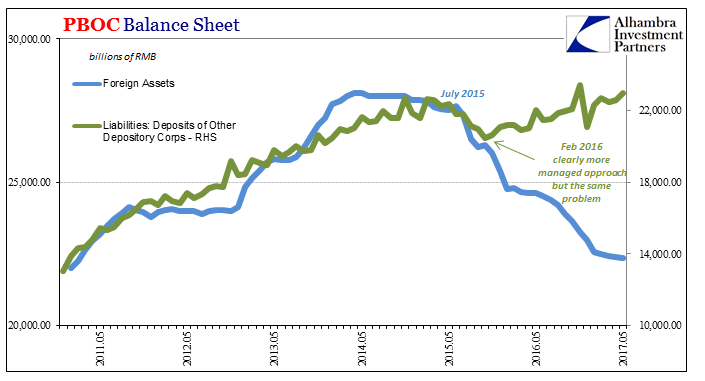

They didn’t solve the baseline issue of the “dollar” because it isn’t something that any single country can. Again, the PBOC as well as Finance Ministry have been responding to Chinese symptoms and often starting from a less than ideal position (especially the PBOC balance sheet). At some point, even Chinese economic agents need more than rhetoric and promises, they need to see that something, anything, has meaningfully improved.

The behavior of Private FAI shows clearly that these same economic agents aren’t finding things different, or nearly different enough. The global eurodollar economy drags onward, varying only between periods of contraction and not contraction. There is no real growth, even in China, by which to create the foundation for real reflation, let alone recovery.

Having lost one decade already, from even the Chinese perspective where so much optimism resides(d), we start a second sadly still stuck on the same level.

Stay In Touch