One day after the China’s government reported disappointing but consistent trade figures, that country’s National Bureau of Statistics published inflation estimates that are being branded at least on this side of the Pacific as some degree of “hot.” As is usually the case, the characterization is wildly off. China is no closer now to an inflation problem, thus solid growth, than anywhere else in the world today no matter how many times a mainstream story uses the words “strong” and “robust.”

China’s producer prices were surprisingly strong in October, while consumer inflation picked up pace in a sign the economy remains robust, with analysts expecting further price pressure as the government’s crackdown on smog hurts factory output.

Growth, however, has remained strong this year, thanks to a construction boom that has drive up raw materials prices and in part fed inflationary pressures. Analysts say ramped up rules to bring polluting factories to heel will add to the price pressures.

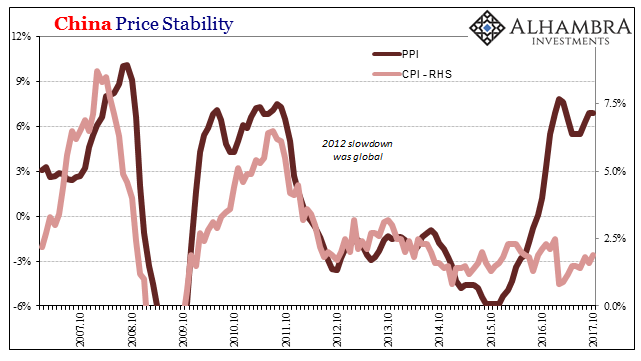

The Producer Price Index is mostly what gets people’s attention. It first turned negative in April 2012 coincident to the global economic slowdown. The PPI remained in subtraction (deflation) for an astonishing 53 straight months, only emerging on the plus side last September.

Having moved positive, China’s PPI now rises consistently at rate of more than 5%, including a 6.9% year-over-year gain in October 2017. It has been 5.5% or better in each of the last eleven months, a record of inflation that seems to be indicative of something like inflationary pressures.

Again, linear interpretations make analysis more difficult than it needs to be. We tend to focus on the plus sign as if it is completely independent from what happened before. To reiterate, producer prices in China declined for just about four and a half years. Toward the end of that period, starting in early 2015, prices declined by more than 4% in fourteen consecutive months, at greater than 5% for six straight during the worst of the global downturn at the end of 2015 and the start of 2016.

Needless to write, Chinese prices driven by commodities have a lot of ground to catch up (actual reflation).

That’s only one part of the inflation description, however. Consumer prices in China bear no correlation whatsoever with producer prices. This is new, not something we find anytime else in a little more than two decades of historical Chinese figures.

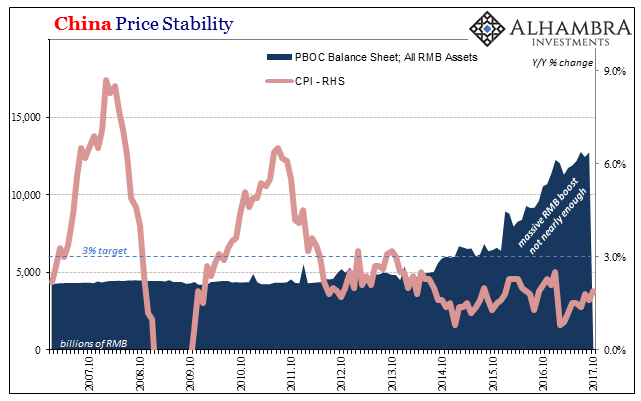

The CPI rose by just 1.9% in October, the 47th month in a row of undershooting the government’s explicit definition of price stability (3%). Like the Federal Reserve, no matter what happens in commodities in an immediate sense it doesn’t translate into behaved consumer prices.

Starting with the Asian flu downturn in 1998, consumer prices consistently followed producer prices as you might expect; producers in recession or a downturn cut prices which are then passed along to consumers, just as in a healthy, growing economy, as China’s certainly was during its upswings, producers pass along price increases to consumers. It all changed, importantly, in 2012.

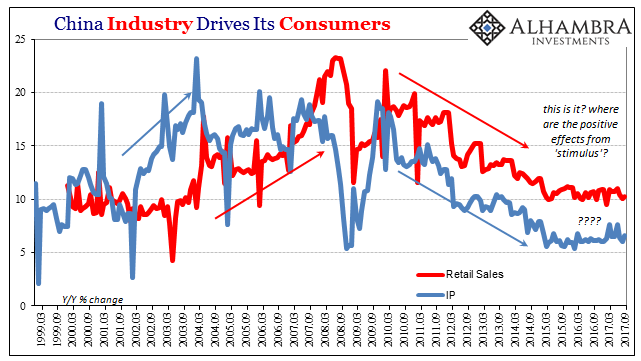

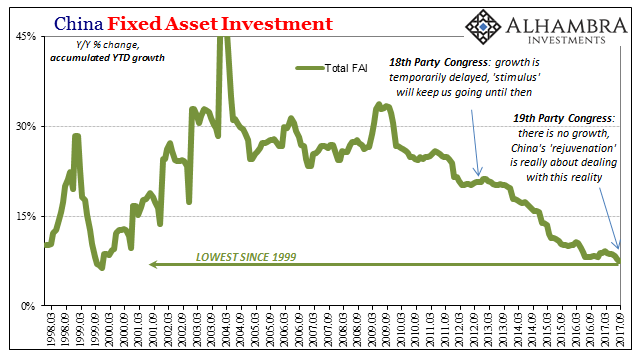

The one time you anticipate a divorce of producer price gains from consumer prices is if commodities rise in an otherwise unhealthy economy where demand is not consistently robust to absorb price increases. By count of China’s CPI as well as the Big 3 econoimc numbers (IP, Retail Sales, and especially FAI), that certainly seems to be the case and then some.

China’s economy is nowhere near strong and the clear divergence between its PPI and CPI is perfectly consistent with a struggling economic system. They are stuck in a no-growth world that several forms of “stimulus” and other countermeasures have consistently failed to break out of. It leads to only bad choices and scenarios:

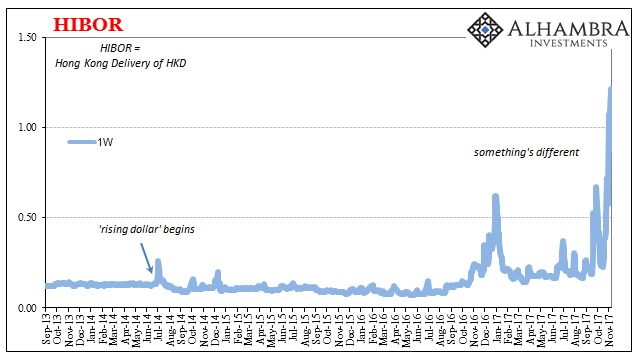

It is from this perspective that the desperate Hong Kong gamble actually makes some sense. The Chinese cannot right now de-dollarize, and so the best option among only bad options appears to be do whatever it takes to stabilize CNY if in the longshot possibility it restarts “dollar” inflows.

Now it just might be that this Hong Kong effort is blowing up right in their face (what happened in Japanese stocks last night? Where does China often get its “dollars” from?). You don’t go for something like that if things are looking up, following the PPI; you do it if it seems nothing else has worked, or can work, a situation strongly suggested by the CPI.

So often it is the case of intentional bias, especially for Economists and the media who faithfully follows them. Usually contradictions are at least taken from separate series (such as the US unemployment rate, which the mainstream desperately wants to be correct, and a whole host of wage and income data that conclusively show that it is not). In the case of China inflation, refutation of the always-optimistic view is provided by the other side of the same data.

Stay In Touch