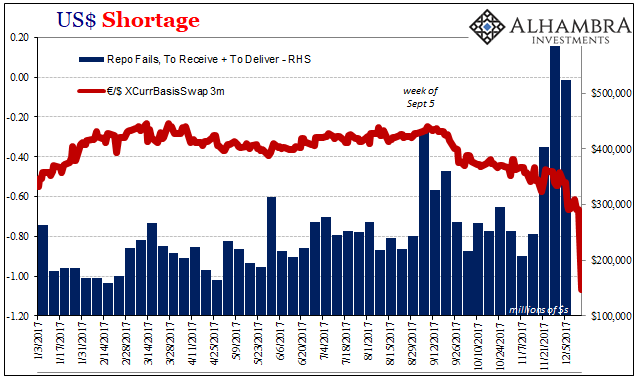

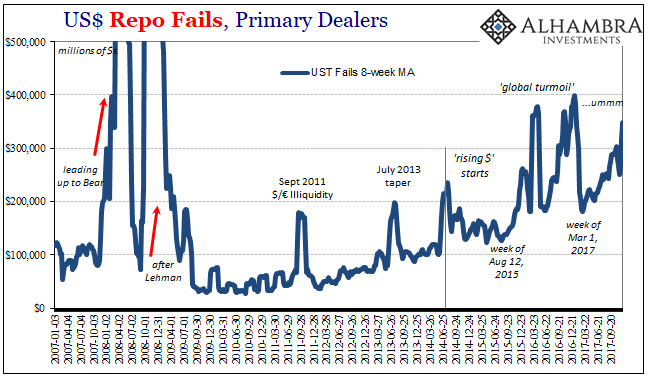

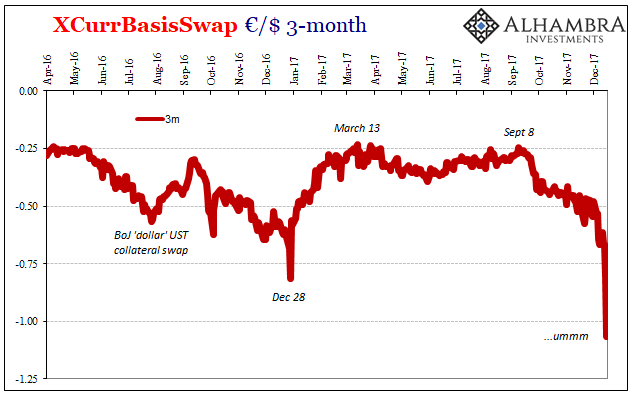

We ended last week with a clear sign that global “dollars” are in (escalating) shortage. I would write “again” with that sentence but there is every indication that said shortage never really ended. It’s not like last year’s “reflation” was a switch from insufficient supply to sufficient, rather it was a relative change to a degree that isn’t easily established – and may not have been all that much to begin with (economic stats sure look that way).

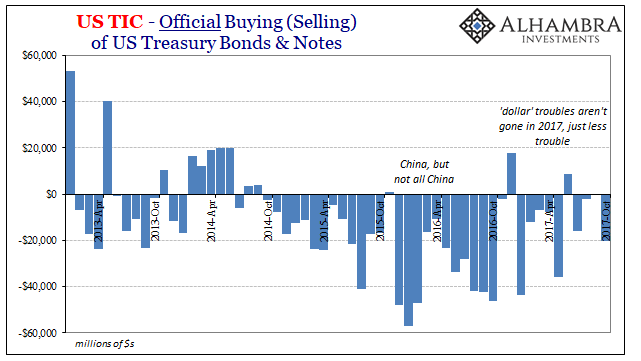

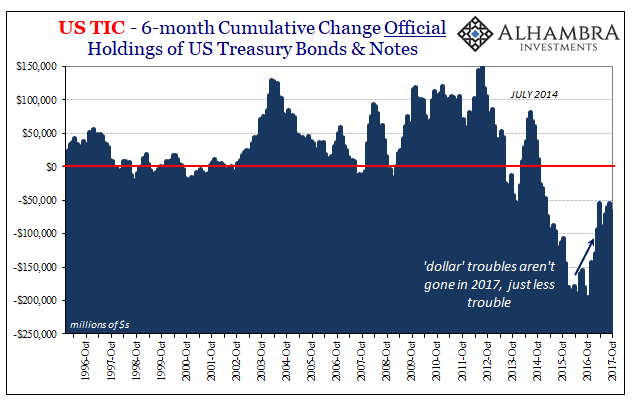

The latest Treasury International Capital (TIC) estimates for the month of October 2017 demonstrate that distinction very well. The official side, where foreign central banks and other official accounts operate, is still “selling” UST’s and other US$ assets at a serious rate in 2017. October was no different. What’s changed is that they aren’t steadily selling as much as they were during the “rising dollar” of mid-2014 to 2016.

It indicates a serious funding gap this late into a year where conditions were expected to be if not normal than at least moving unambiguously in that direction. Where TIC truly helps is in more than confirming “dollar” issues as a matter of supply, giving us some needed insight into distribution (and redistribution).

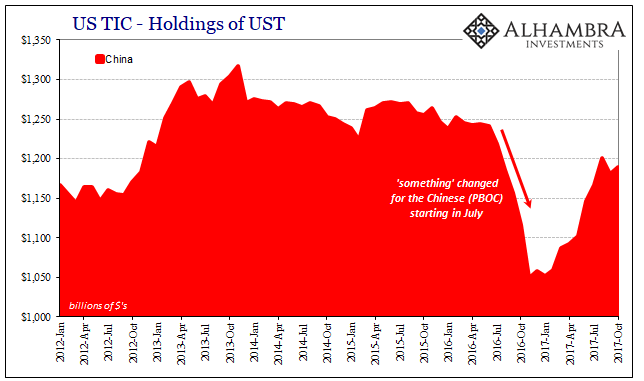

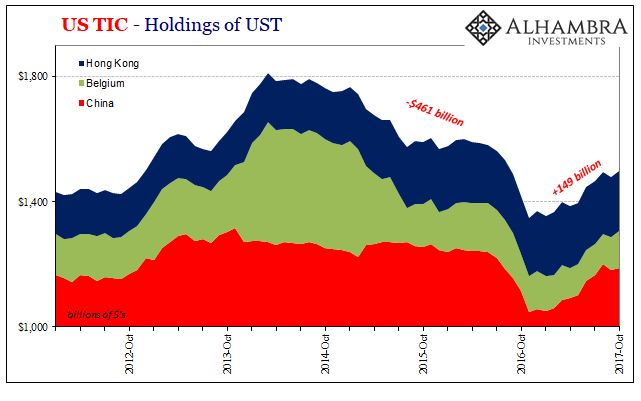

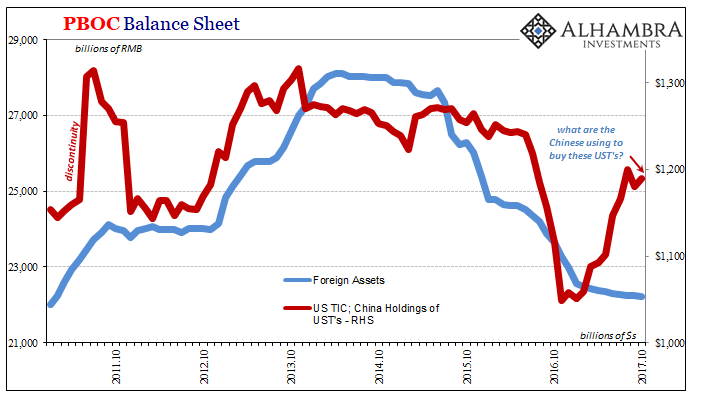

If we look at China, for example, it appears as if the Chinese have nearly solved their imbalance. Being forced to dump nearly $200 billion in UST’s in just five months starting in July 2016 through last November (coincident to further CNY “devaluation”), TIC figures show China gaining $140 billion of them back March through September (coincident to CNY’s suspiciously remarkable recovery).

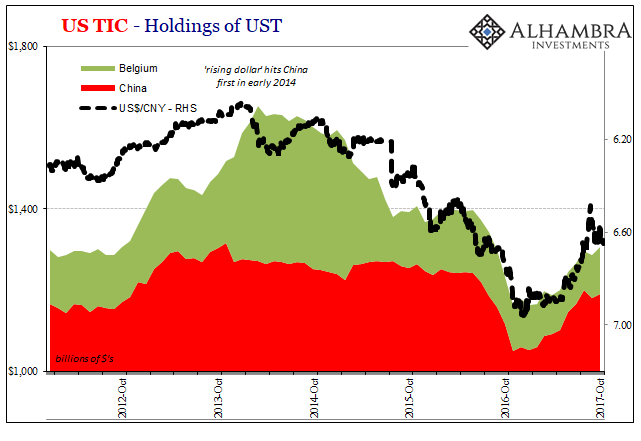

The Chinese, as does everyone else, have many pockets including those able to channel significant “dollars.” One of them is stitched into Euroclear (the big European derivatives clearinghouse) residing in Belgium. If we add Belgium to China’s holdings over the past few years, the gap is revealed as significantly larger (as well as matching almost perfectly CNY’s “rising dollar” history).

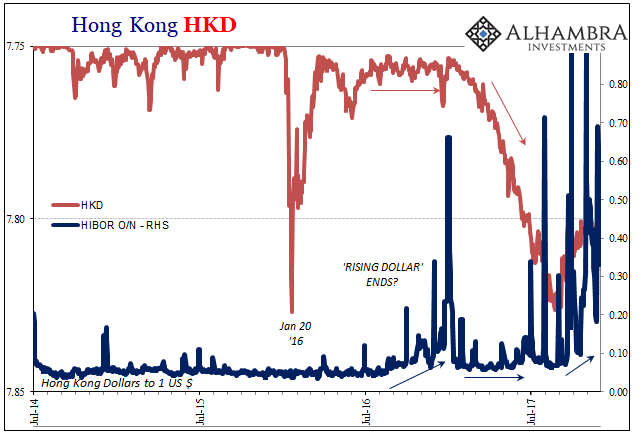

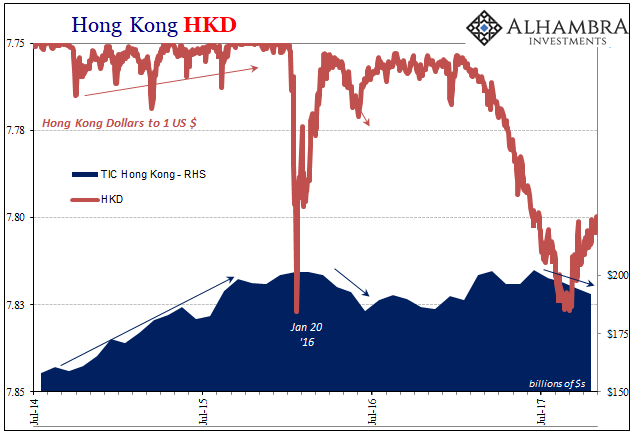

In addition to Belgium, Hong Kong has also been drawn further and further into China’s international funding quagmire despite what is supposed to be a completely separate monetary system. HKD was left in place after the British handover, along with the HKMA, to reassure the rest of the world that Hong Kong was going to remain a stable, individual haven for financial trade throughout Asia. The city was always a significant money center going back to the British and sterling as the reserve currency.

To be using HK like they are suggests just how desperate Chinese officials might have become in the face of an intractable and, from their view unsolvable, monetary conundrum. Yet, there is no doubt that they are, starting from the acknowledgement that Hong Kong has no “dollar” problems of its own – at least until around January/February 2016. But that can’t be traced to anything specific to Hong Kong apart from its necessarily close relationships with RMB.

Adding HK’s woes to China’s including Belgium, the rebound in Eastern “dollar” conditions is much less impressive. Instead, like the overall TIC estimates, the best that can be said is that it’s not as bad this year as last. Such a relative rather than categorical change doesn’t mean as much as you might think – just as Hong Kong.

High to low, China + Belgium + Hong Kong were divested of almost half a trillion in UST’s. And yet, UST yields moved lower coincident to all that “selling.” How many times have we heard that China was going to sell “all” their Treasuries and bring down the US? Well, they did something like that and it was worse for them and good for nobody.

Since the trough last November, only about a third have been bought back (and UST yields are generally higher for that “reflation”). It’s about as good a real-world demonstration of the interest rate fallacy and global “tight” money (eurodollars) as we might hope to ever get.

But the “selling” isn’t over with; not at all. That’s largely the point here. While China on its own appears to be have overcome its deficits, it’s a mirage of accounting. In other words, the TIC figures add to other data and market prices in illuminating intentional redistribution efforts that can only be traced back to an ongoing global funding problem.

For as much as we focus on China (not without good reason, of course), the Chinese are not alone. There are funding gaps showing up in many places around the world in 2017 that aren’t nearly as different from 2016 and before.

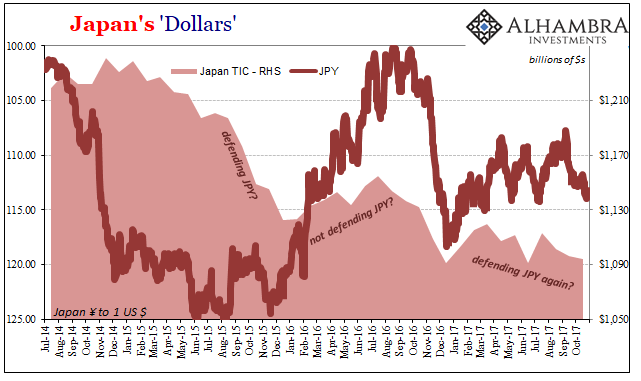

Going back to November 2014, the Japanese have expended $147 billion in UST’s at various calendar points to “defend” the yen. Normally when you apply that term to a currency it is to like CNY maintain a steady exchange or even a rising one; anything but “devaluation.” In Japan’s case, however, the direction the BoJ wants the currency to go is down, therefore any defense (loosely speaking) is of that policy not what applies elsewhere as normal.

And it doesn’t necessarily mean that it is BoJ undertaking any actions on its own. As with the PBOC, BoJ can try to apply leverage and use moral suasion to get Japanese banks to act more in line with its goals. One example of that is last July’s “helicopter” disappointment that in eurodollar terms was instead a big (if temporary) boost in allowing Japanese banks to swap JPY bonds for UST assets (turning yen assets into US$ repo eligible collateral).

After that “dollar” program was introduced, TIC records a large reduction in Japanese holdings of UST’s all the while JPY peaked and then, as BoJ likely wished, fell sharply (“reflation”) in the policy direction. This year the results are far more mixed, with JPY exhibiting the wrong overall bias again. Not surprisingly, Japan’s UST holdings are moving lower almost certainly trying to hold JPY from more appreciation than it has already obtained.

Monetarily speaking, this year is closing out far too much like last year. We might have hoped that at worst 2017 would be something of a transition year, where it started out in rough shape and then gradually improved as the months went by. That just didn’t happen, where instead around March whatever was going to get better did. Then something changed in September and it’s been a downward slide toward the finish ever since.

“Reflation” just didn’t make as big a difference as was expected. In functional terms, it didn’t make any difference at all.

Stay In Touch