It seems as if we’ve found one of those interim periods that often accompany times of uncertainty. Markets, stocks as well as bonds, are in a wait-and-see mode. Either the next shoe drops, as is feared, or the grand response works, as is widely hoped. Which way are the risks perhaps rebalancing?

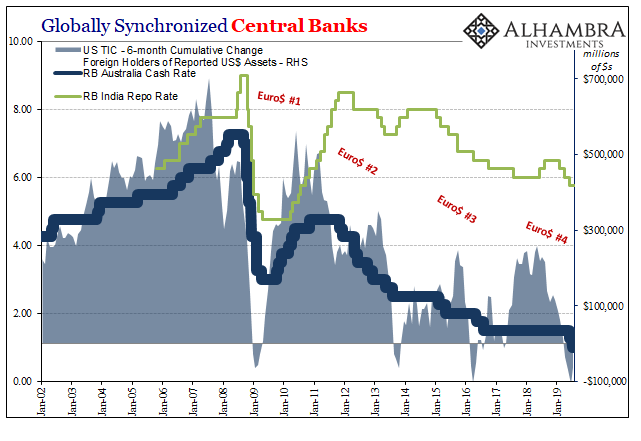

The global downturn that developed late last year caught most off-guard (though it shouldn’t have, the curves were on it from the beginning; before the beginning). We’ve been over it a million times: globally synchronized growth was supposed to mean a worldwide inflationary expansion for the first time in over a decade, instead it has become that same sinking, deflationary downturn feeling. Even though it’s more than eighteen months old, we still don’t know where or how it might end.

Dismissing it as nothing-to-see-here, the combination of “transitory” factors which were to dissipate all on their own, by midyear officials began to finally see how there was more going on. There really was something to the downside beyond minimal and temporary cross-currents. One by one, central bankers started to strike back.

And that’s largely where we are today. Markets are right now wondering, did it work? That’s the interim, caught between the downturn that prevailed under ignorance and what might come next as “stimulus” is offered. The deliberate processing of incoming data to parse a possible change in trend – good or bad.

The one place that doesn’t quite fit the profile, though, is China. The Chinese economy more than any other will probably determine our ultimate fate. And that, of course, means dollars.

The PBOC was way ahead of its worldwide counterparts. It had begun “stimulus” in the middle of 2018, not the middle of 2019. Only, it hasn’t actually been stimulus – which is why the spreading global downturn and continued uncertainty. China’s central bank had responded long before the others, more than a year before any other, but it doesn’t seem to be having any positive effect.

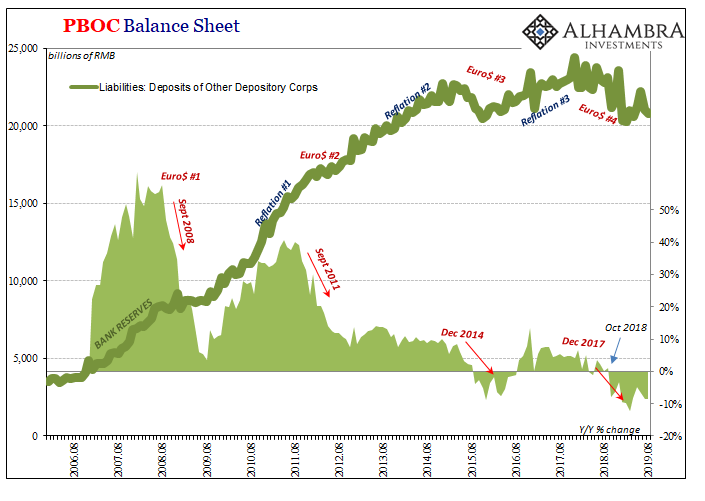

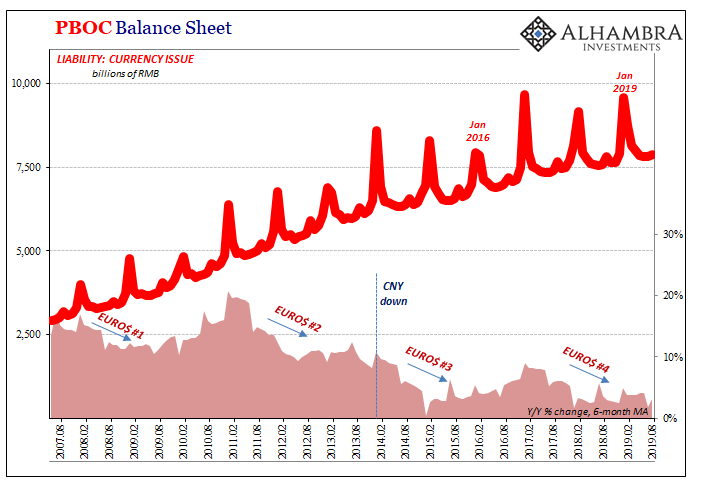

Primarily, Chinese authorities have been attempting to manage their dollar shortage with the private monetary offset of the RRR cuts. The two go together: fewer dollars means fewer assets which, in central bank accounting, means fewer liabilities. Central bank liabilities, at least in China, are what counts as money and currency. Bank reserves and physical issue.

In that way, the RRR’s are not additive they are merely an intended replacement. Not stimulus, but hoped-for managed decline. That’s pretty much how China’s economy has fared ever since Euro$ #4 flared up. It isn’t crashing and falling apart, at least not yet in the mainstream, official stats, but it sure isn’t being stimulated, either.

As China heads toward the next Golden Week on the calendar, its National Day begins tomorrow, the economic and financial system continues to grapple with constant pressures. To begin with, as we’ve noted all along, the PBOC is forced to trade bank reserves for minimal currency growth.

According to the latest PBOC balance sheet update through the month of August, bank reserves (Deposits of Other Depository Corporations) contracted sharply for still another month. Down an additional 8.7% year-over-year last month, the average continues to be also less than -8%, sustained, which is several percentage points less than during the worst of 2015-16 and Euro$ #3.

This is why there are continued RRR’s. If the PBOC cannot supply that sort of interbank liquidity, then it has few other options besides hoping China’s banking system will make up at least some of the difference.

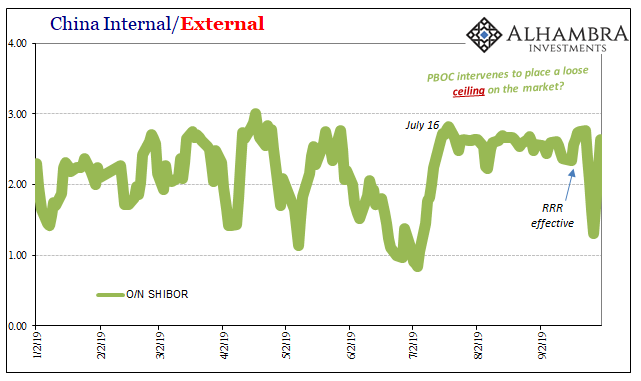

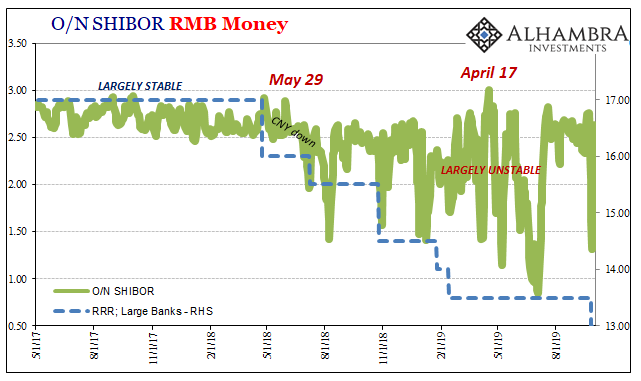

On that account, the verdict isn’t favorable. The overdraft rate, overnight SHIBOR, continues to act strangely. In the first few days after the last RRR cut (September 16) there was little or no notice of it in the RMB market (which was opposite the prior trend; a drop in the overnight rate had preceded recent RRR’s). Instead, SHIBOR pushed upward to and maybe even slightly above what has looked like an imposed soft ceiling.

On September 24, the rate of 2.759% was the highest it had been since mid-July. But then last week, an additional liquidity push, O/N SHIBOR tumbled to a low of around 1.21% – only to spike back to 2.635% today just in time for weeklong bank closures associated with the Golden Week.

In other words, we have no real idea what effect the last RRR cut may have had – or may not have had. We won’t likely know anything until China reopens. If you remember what happened last year, under similar circumstances (though the RRR cuts followed that holiday), it didn’t work out all that well for anyone. The landmine soon thereafter.

Which may be why the last RRR was moved to beforehand as well as the SHIBOR “ceiling.”

This mess of volatility and unpredictability in a key RMB marketplace, and all for the barest minimum of currency growth. While it took another near 9% drop in bank reserves to create the room for them, currency issue in August 2019 gained just 4% over August 2018.

That’s actually up a bit from earlier this year when currency growth had been squeezed down to less than 3%. That to me looks like intent; a choice to double down on the RRR’s knowing that bank reserves would have to continue falling by so much in order to fit in just a little more currency.

Whether there is a material difference between 4% currency growth and 2.8% remains to be seen. To get to Reflation #3 in China that had meant near 10% expansion in currency as well as a complete turnaround in bank reserves.

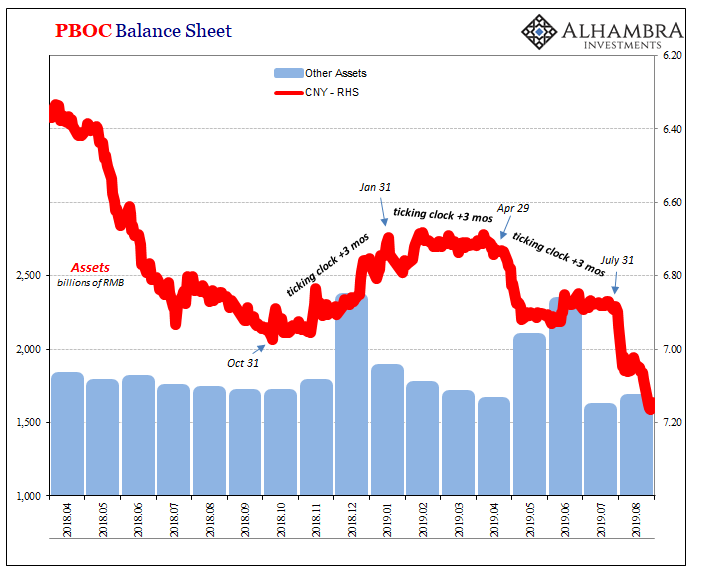

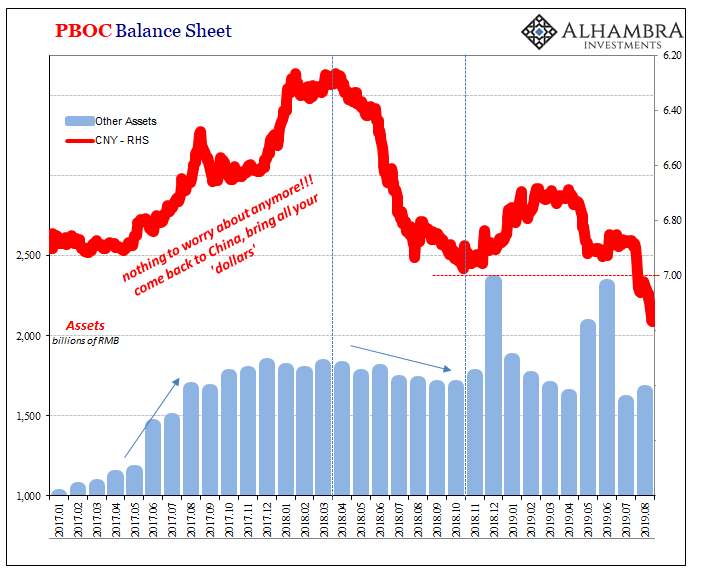

And we haven’t even gotten to CNY yet. As far as these ticking clocks go, they keep ticking though what might really be behind the clockface doesn’t always chime regularly. On the PBOC’s balance sheet, the pattern remains elusive overall but suspicious in some details.

The “bigger” interventions in CNY seem to show up in the PBOC’s “Other Assets”, those which are intended to move the currency upward (by “supplying dollars” either directly or via cover to Chinese banks) as in December 2018 and April/May 2019. When there is no pop in Other Assets, as over the last few months or during the middle of 2018, the currency exchange rate tends to fall farther and faster.

In other words, these don’t appear to be the ticking clocks themselves, rather extraordinary and likely short-term supplements to them. And with CNY better behaved in September, it will be interesting to see if the same pattern plays out in Other Assets (with the next clock scheduled for expiration at the end of October).

In economic terms, all this continues to be spelled out under managed decline. The Chinese economy, again, doesn’t seem to be crashing. But it doesn’t seem able to get back on some positive track, either.

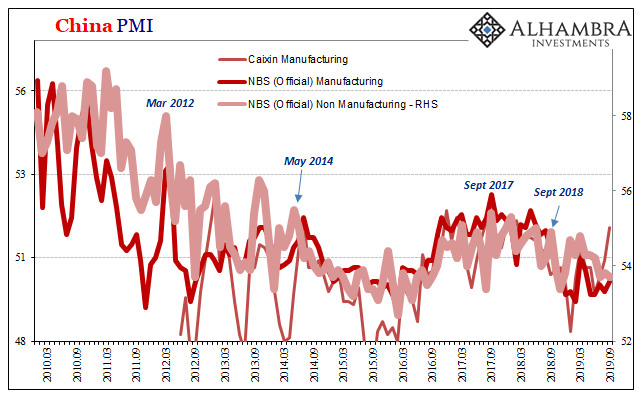

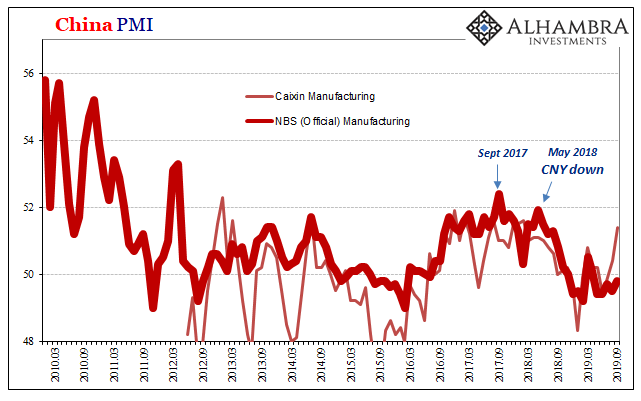

China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) reported last night that both its PMI’s disappointed for what was supposed to have been a more significant rebound in each. The ups and downs are commonplace, a somewhat higher degree of variability month-to-month especially on the services side.

Instead, the NBS estimate for its Non-Manufacturing PMI declined slightly to 53.7 in September 2019. That was down from 53.8 in August, and equal to 53.7 in July. Not only does that continue the slowing trend which has been in place since September 2017, it might suggest more downside than upside in recent months.

In manufacturing, the official PMI improved to 49.8 which was less than the anticipated rebound back above 50. Instead, it was the fifth straight month on the wrong side of 50, and eight of the last ten dating back to December 2018. During Euro$ #3, the index was underwater in only seven months total up to and including February 2016.

This was balanced somewhat by the private Caixin survey which measures sentiment among more medium and small-sized manufacturers. This alternative PMI increased to 51.4 in September, up from 50.4 in August. As you can see below, though, the Caixin tends to be more volatile and noisier (and stands out as an outlier when it is).

For global markets seeking any sense of a positive payoff from official action, there’s little to suggest China can be the source of a turnaround. The PBOC continues under enormous constraint in order to haphazardly shoot for managed decline as the upside. Those constraints show no sign of abating.

While time may seem to be a positive factor here and elsewhere – it hasn’t gotten too much worse therefore the more time passes the greater the likelihood it won’t – it does seem as if markets, at least, appreciate the reality. The longer this goes on the greater the chance something does break, something does really go wrong, and that’s where managed decline becomes something altogether worse.

And let’s be clear, managed decline in China is already pretty bad. Where else do you think this global downturn and these global risks came from? Trade wars?

Stay In Touch