It’s all somewhat confusing, once acclimated to this new paradigm. The highest in years can still be nearer the lowest in history. Given that apparent contradiction, it seems as if only one of those perspectives can apply. Which one you focus on often depends upon which way you already lean.

Toward the end of last year, mortgage interest rates had climbed up near 5% (average 30-year). It was the highest since early 2011, a surefire calamity for the housing market. And that market was under severe pressure. In terms of volume and even prices, real estate was experiencing its greatest slump since the big bust.

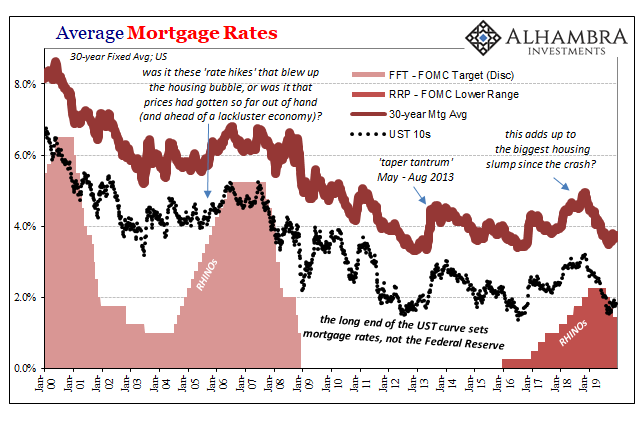

But a 5% mortgage rate really wasn’t that big of a deal. Closer to record lows than the vast majority of modern American experience, it was akin to being the least low of a period of only low rates. It wasn’t the bogeyman rising rates had been made out to be; as if 244 bps in federal funds could ever make that much of a difference.

Part of the problem, most of the problem, lies in that very idea; that the Federal Reserve is at the center of all this. For the first time in a decade, the FOMC was voting regularly for rate hikes therefore the highest mortgage rates were just following along. Everyone said the Fed overdid it and that’s what did in housing.

And it is one of a litany of economic (small “e”) assumptions that is demonstrably false. The central bank no more sets the average mortgage rate than does Congress, or you and I for that matter.

Mortgage interest is derived directly from bond interest, and the bond market had little use for Janet Yellen’s and then Jay Powell’s rate hikes in name only (RHINO). Thus, in the grand scheme of things, which is what truly matters, mortgage rates barely budged. On the chart above, last year’s huge deal is barely detectible all its own.

The reason mortgage rates didn’t rise that much was because the bond market wasn’t as enthused about the economic situation (which is why the BOND ROUT!!!! the same everyone was screaming about never happened). Maybe there was some small chance that things were really getting better, that the boom in word might become a boom in deed, but balance of probabilities it was never likely.

As a result, the highest rates in years didn’t really mean how it sounded.

Just like that, throughout 2019 rates went right back to their now-normal condition. Having not that far to go, historically speaking, by early September the average mortgage was being booked at very close to historic lows again (for the third time since 2011). In that grand scheme, it is these lows that stand out.

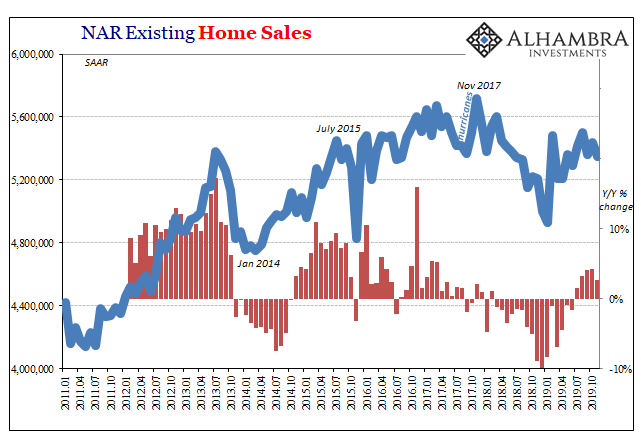

For the housing market in late 2019, though, not as much. According to the National Association of Realtors’ (NAR) estimates for resale volume, the housing market remains in its slump despite the average mortgage rate having dropped to about 4% by the end of March, and consistently below that level since the end of May.

Sales have rebounded since their lowest point, but remain way, way off the pace from before the slump (which began, you should note, at around the same time, late 2017, as everything else around the global economy “unexpectedly” dumped). Rates may have been a mild headwind heading toward 2019, but in 2019 they’ve again switched to a tailwind and not by matters of FOMC policy.

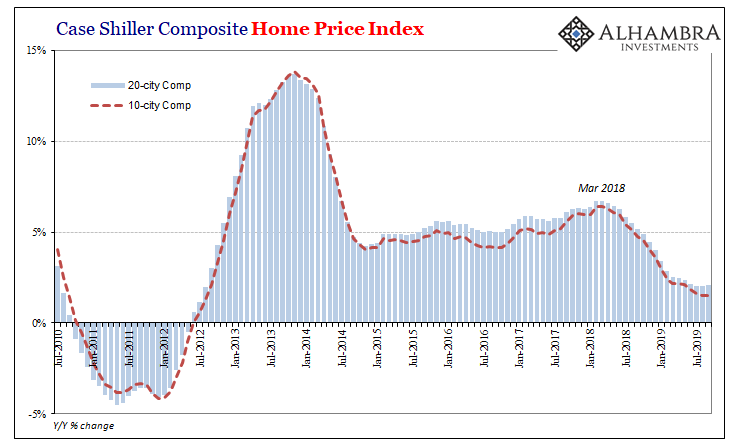

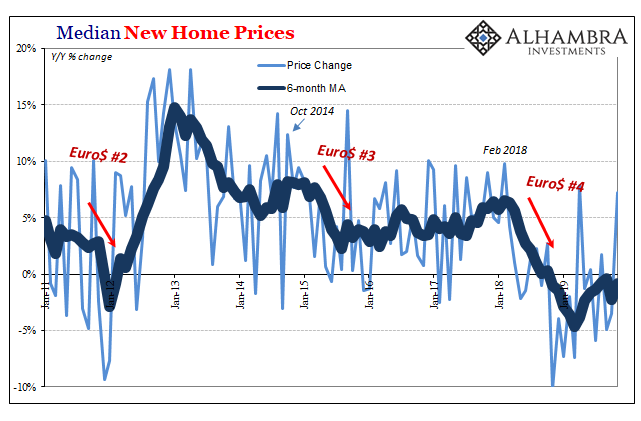

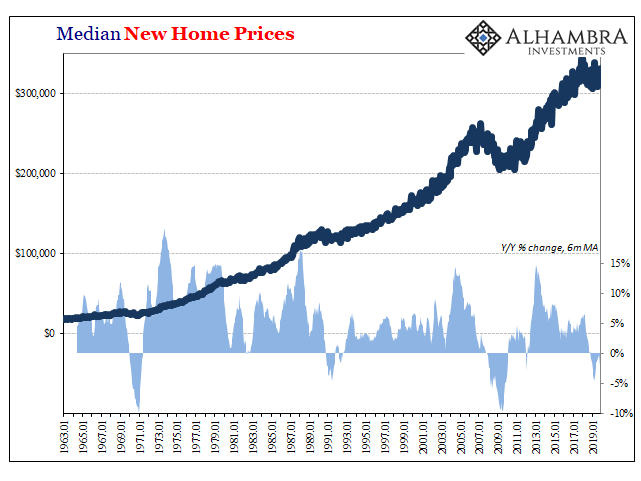

If anything, it is prices what might be keeping the market at least afloat. From Case/Shiller to the Census Bureau, it has been the most serious and sustained discounting (at the margins) in a long time. Combined with the unintentional aid of lower rates, these are the only strong points in the housing data – and they have arisen from weakness.

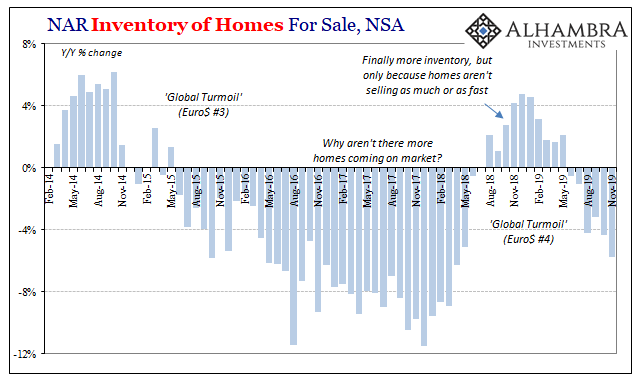

Home price appreciate continues to be less-than-robust despite the fact that the NAR says Americans remain unusually shy about selling the homes they already own. Inventory levels, for several years blamed for the acceleration in home prices, are falling again without this time having led to that same dynamic.

Decelerating inventory and now slowing home prices? Something is missing.

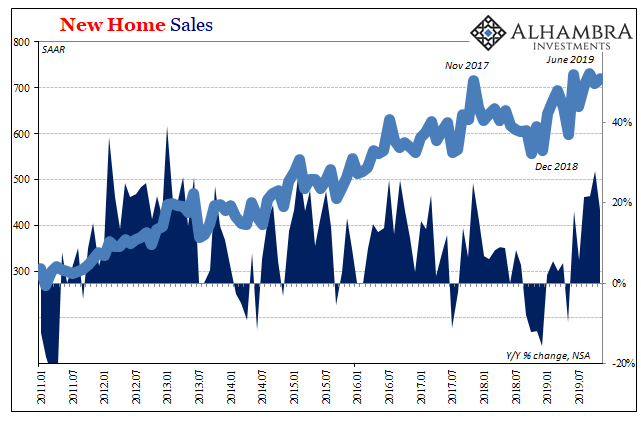

In terms of new homes sold, those just erected and turned over, the rebound in 2019 has been more noticeable. But even here, that trend has gone sideways again (since June) even as mortgage rates fell toward, and remain near, record lows. A clear stall in the comeback.

In all likelihood it was the much bigger price discounting here which explains the relatively more noticeable bounce. Whereas in existing home sales there was some at the margins, the data for new home sales shows how extensive it had been. This year has been a real bargain hunter’s dream, some of the largest price reductions in more than a half century of data (take that, 50-year low unemployment rate!)

What I’m getting at is pretty simple; the Fed didn’t cause the housing slump with its “rate hikes.” Just like 244 bps fed funds didn’t put the economy into its downturn.

And if the Fed didn’t break it, then the Fed won’t be able to fix it with a few rate cuts. The bond market has already supplied the equivalent of six of them to the average mortgage rate, and so far the real estate data is more about price sensitivity than that positive swing in payment-related buying power.

But if those are actually the tailwinds behind the housing market propping it up only somewhat, what is the headwind seemingly still holding everything back?

As has become typical, the negative effects of these Euro$ problems just go unnoticed. Outwardly the economy was booming in 2018 and outwardly everyone agreed with that idea. At the same time, though, uncertainty became more than just being unsure about the narrative.

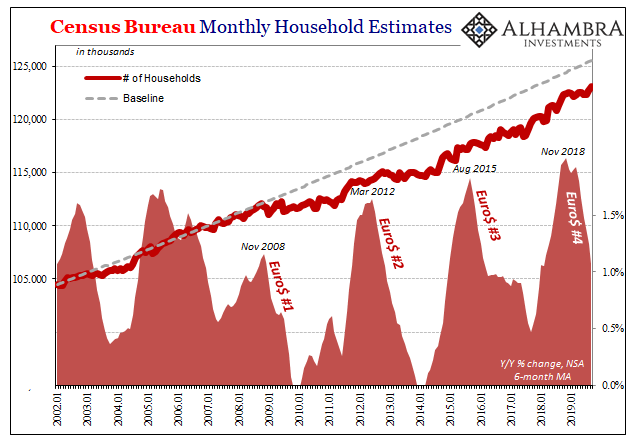

The Census Bureau also estimates that growth in the number of American households lags each of these Euro$ squeezes. It’s an obvious headwind for housing as it means slowing real demand for it.

But it’s so much more than that, and tells us something more than how it might relate strictly to demand for dwellings.

Americans, at the margins, unwilling to go out on their own (not just the proverbial millennials stuck in their parents’ basement) are making a statement about the strength of the real economy underlying the One Big Number (3.6% unemployment). The TV says the economy is strong, and Jay Powell is on it every other day making that declaration, but more are actually wondering (to themselves) whether or not it really is.

Housing by itself won’t do much for (or to) the economy either way. Unlike decades ago, a prolonged and stubborn housing slump isn’t going to produce a recession. Instead, the real estate market is a barometer for the hidden process that still could.

The continuing depressiveness of housing suggests that as 2019 draws to a close the downside risks remain for a lot more than this one part of the economy. Despite a double dose of unintentional aid (prices and rates), there must be serious countervailing forces more than balancing those out. Ironically, that’s what the price trends and persistently low interest rates suggest, too.

Stay In Touch