It is the inversion of the seventies. Four now five decades ago, the economy was caught in the grips of an inflationary condition it seemed unable to escape. It just went on and on, and while it was roaring officials up and down the spectrum assured us that they were doing their best, the only things that were able to be done (even idiotic Nixonian interference like wage and price controls).

Toward the end, of course, we found out that just wasn’t true. The problem wasn’t so much embedded idiosyncrasies within the economy (like “cost-push” labor inflation) authorities had been helpless to overcome, rather it was the rigidity of central bankers who petulantly refused to understand their jobs. They blamed us and, as usual, the problem turned out to be them.

All you have to do is put together the names “Arthur” and “Burns.”

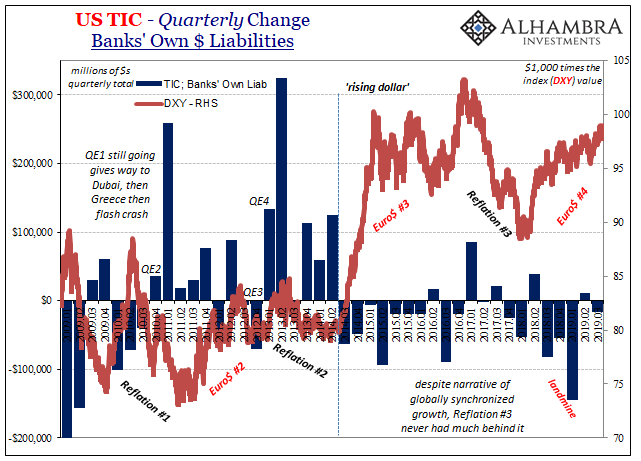

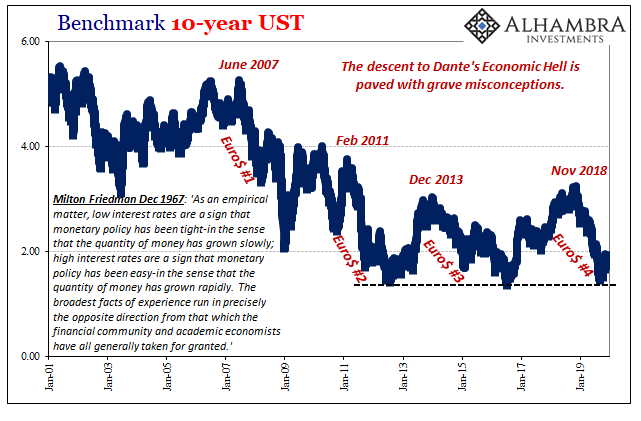

Today, it is the reverse. Not the “us” versus “them” part, that’s the same. Only now the whole global economy is swept up in a deflationary pit from which it again seems unable to transcend. It is not deflation in the 1930’s sense, rather it is a slow squeeze, an unceasing downward (monetary) drag that intermittently ensnares the global economy keeping it from taking off at just those moments it looks best able to.

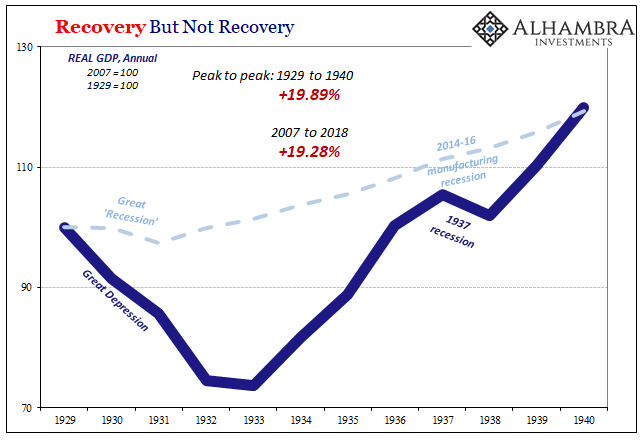

As a result, the last decade plus actually underperformed the Great Depression. Think about that.

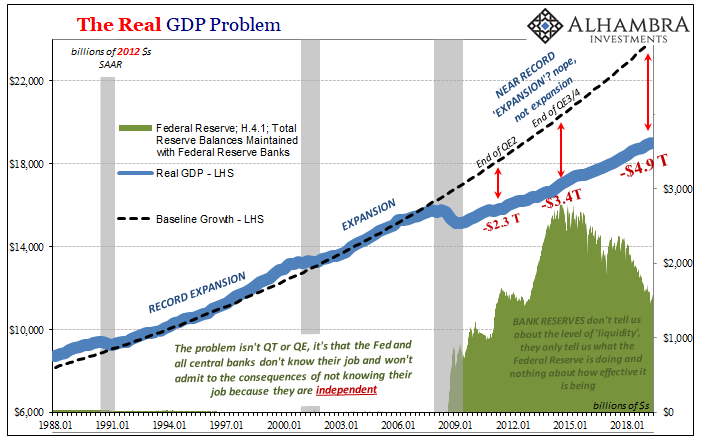

How can this be so? Once more, the official nitwits are in uniform agreement. It’s our fault, not theirs. Their courage and bravery spawned countless QE’s and genius “money printing”, each and all the most powerful monetary stimulus ever invented by humanity (which they and their media never stopped telling you).

The answer to the contradiction is allegedly R*. QE and monetary stimulus all worked fine (term premiums), you see, if there is anything wrong then it is because there was no possible way it could have been fixed. It’s the economy that is broken.

That’s all R* really means. It is the so-called supply side backdrop, facets of the economy like productivity and investment which define its real potential.

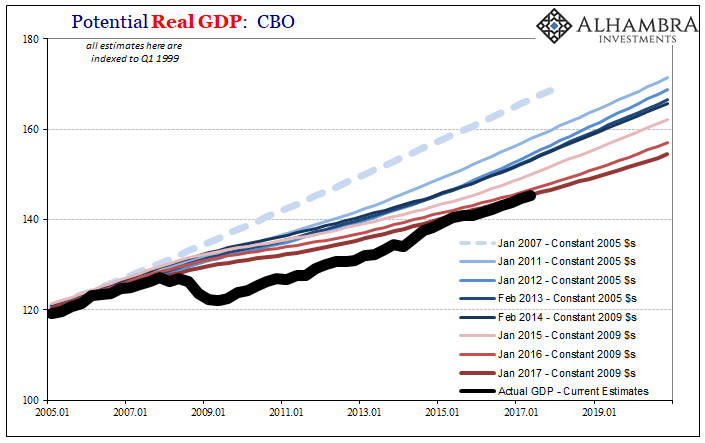

Going back to 2016, Economists and especially central banks have introduced R* and embraced it with all their heart. Why 2016? Because an actual recovery was all set and had been penciled in for 2015 given what had happened (or what officials thought was happening) in 2014. The latter, though, was in reality the final year of actual recovery, it’s last chance.

Even 2017’s globally synchronized growth was downsized by comparison. Though officials still talked it up at every opportunity, they knew full well that 2017’s expectations began and topped out significantly less than 2014’s. Results, too.

By default, those at the Fed have basically accepted the premise of “secular stagnation.” The prospect was first resurrected back in…2014 and 2015. Dr. Larry Summers dug up old Alvin Hansen’s Great Depression ideas and gave them a 21st century update.

Hansen’s premise had been non-macro supply side factors:

By the latter 1930’s, however, Hansen became more cynical about all of it especially after the setbacks in 1937 and 1938. To his view, America had found itself with a structural problem far more intractable than might be cured by even pure Keynesianism. Prosperity and growth had come to the United States based on three factors in varying combinations throughout the 19th century: 1. territorial expansion; 2. population expansion; and, 3. technological innovation. The Great Depression, then, was the opening act of what would happen should all three run dry.

In that situation, as Hansen described it, there was nothing much authorities could do but sit back and hope the desperation didn’t get out of hand. Something like managed decline.

In Summers’ view of it, our modern R* version must be a combination of demographics (aging plus lack of babies) and laziness. Though they are careful to be polite, Economists and officials can’t hold back their disdain for the millions of regular working folks who have been caught up in this mess.

If only Americans (and Europeans) would learn to code rather than turn to fentanyl abuse when their jobs first disappeared – when was that again? – and no other prospects have materialized to replace them. For much of the labor force, especially the younger generation (now two, this has gone on so long), they have no idea what opportunity really is.

It’s something you can only read about in a history book.

The gist of R* stagnation is this lazy, rigid labor force hooked on drugs. Under the thumb of such unreachable “supply side” factors there’s really nothing Ben Bernanke, Janet Yellen, Mario Draghi, etc., could have done differently. They instead believe we should be thanking them it hasn’t been worse.

You can see why in all likelihood R* has become so popular over the last few years in official circles.

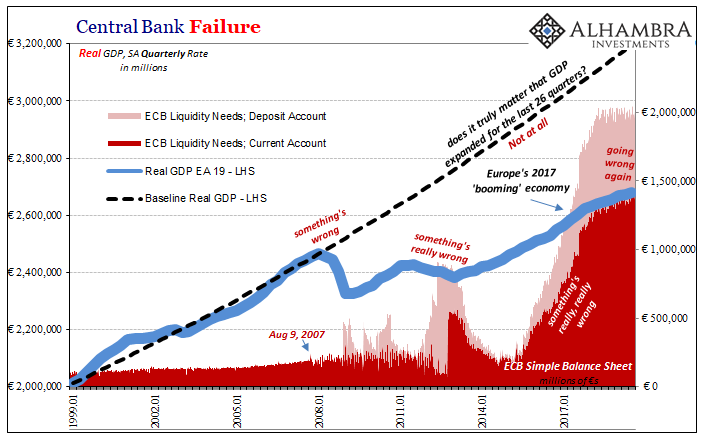

But in recognizing that, you also have to recognize the larger significance. Even officials tacitly acknowledge that there is “something” broken in the economy such that even when they say it is “booming” it really isn’t. Not by any prior standard, anyway. Accepting R* means accepting no-growth as a baseline.

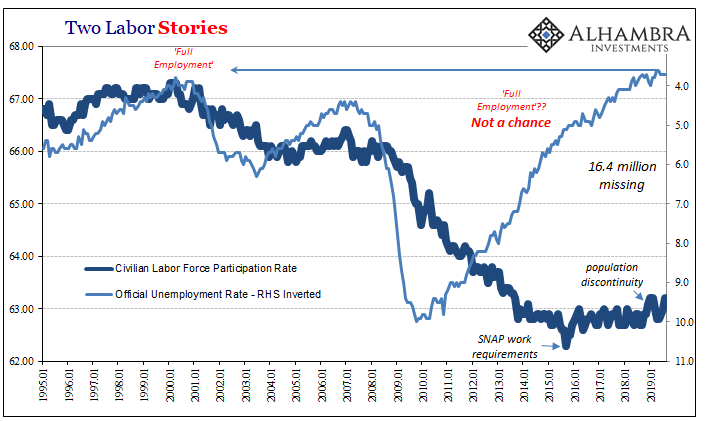

The last few years have presented the R*/secular stagnation view with several inconsistencies, however. The first, slack. For the economy to be broken on the supply side due to its labor deficiencies, you have to embrace the unemployment rate and take it literally.

Long story short: there should have been inflation in 2018. A lot of inflation. There wasn’t.

The problem with R* isn’t limited to what we didn’t see, either. There is a lot which is contradicted by what we did.

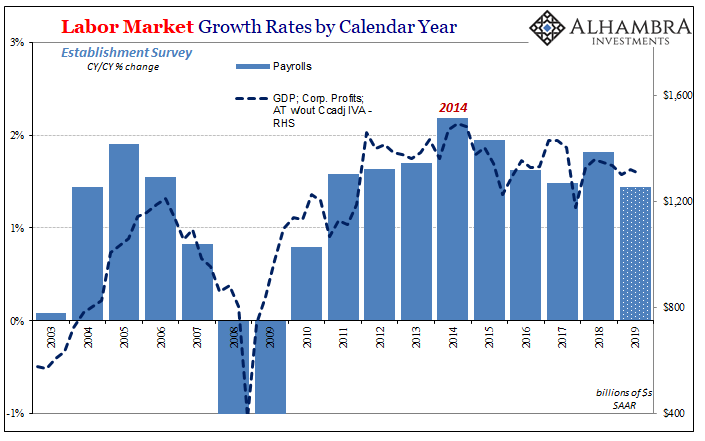

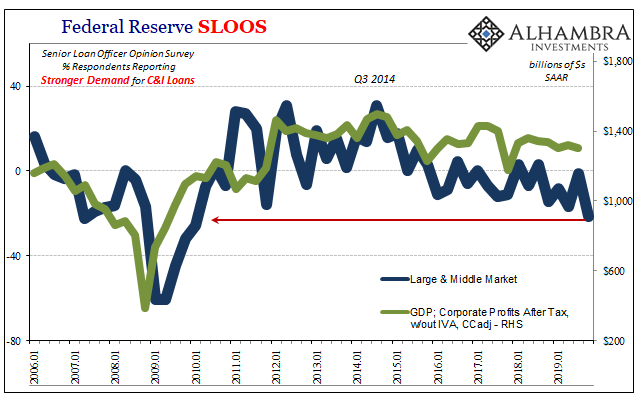

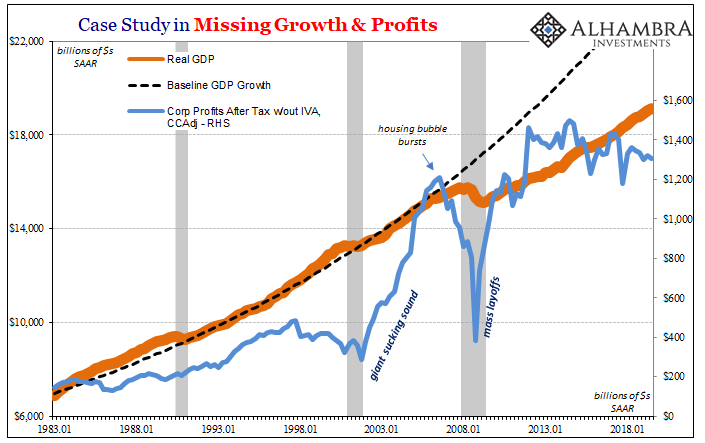

When the BEA last updated its figures for quarterly US GDP, the outfit also updated the portion of it (GDI) attributed to corporate profits. Companies hadn’t been able to restore the same trend in profitability after the Great “Recession” as they might have been expecting from before it.

And that was before 2014.

What the BEA shows is that this one particular year ended up being the absolute peak in profitability. Whatever sluggishness before then, there at least had been some growth and upward trajectory (though never enough). Since then, profits have not recovered, instead sinking (not decelerating, but actually dropping in absolute terms).

What follows from that is every bit just plain common sense – companies that collectively have trouble growing their collective bottom lines are in the aggregate going to overmanage their costs as a result. That means labor as well as capex – the two most significant parts of the “supply side.”

Powell likes to talk about the “strong” labor market but the truth is last year’s employment growth will turn out to have been the worst of the last decade (and that’s before the large downward benchmark revision next month).

How about capex?

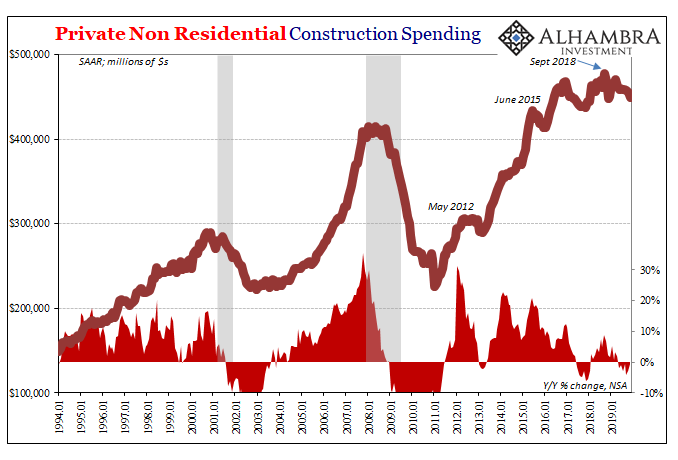

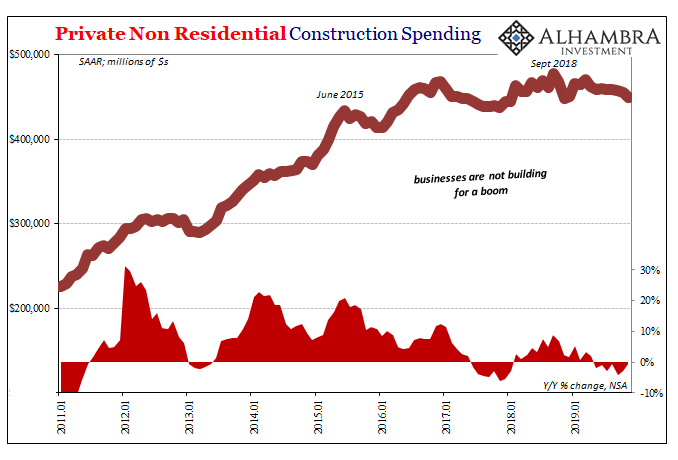

Total Private Non-Residential Construction Spending in November 2019 (seasonally adjusted) is up just 3.7% when compared to June 2015 (when the monetary reverses of 2014 finally caught up to the economy). Not per year, total. Four and nearly a half years and the amount spent on the construction of new supply side facilities has barely budged. It should immediately grab everyone’s attention for reasons that have nothing whatsoever to do with heroin and adult education.

Obviously macro factors.

Since September 2018 (landmine), capex is waning again including the latest downward lurch showing up over the past few months (when the economy was supposed to be getting better).

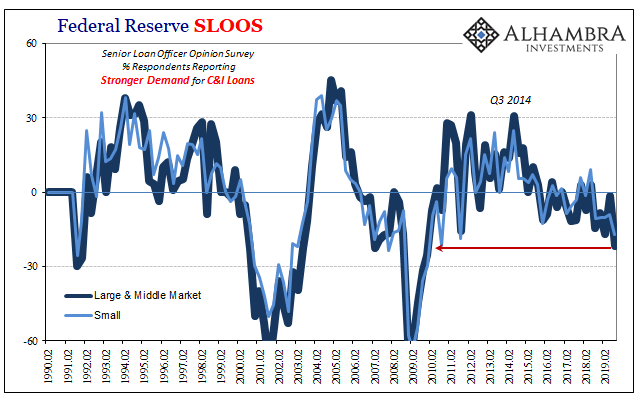

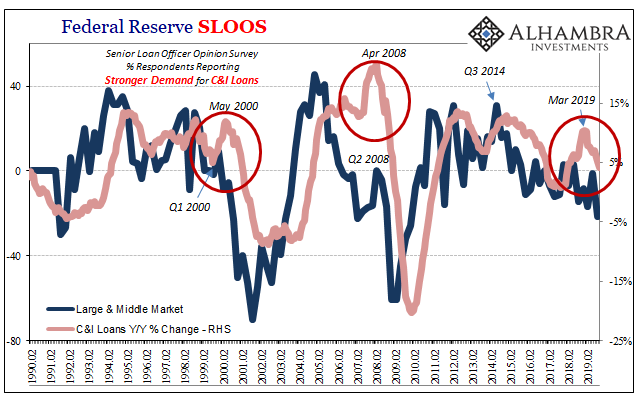

According to the Federal Reserve’s Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey (SLOOS), don’t expect this to turn around any time soon. The Fed asks, as the series’ name implies, those closest to commercial and industrial lending to give their opinions on conditions in that area.

Again, common sense. If businesses aren’t in demand for something like C&I loans, then it is probably because they aren’t optimistic about the need for C&I loans to, among other things, build new facilities in order to expand in the manner a booming overall economy would lead them to. The SLOOS data for Q4 2019 (recorded and released in October) says that the demand for credit funding here is likely the lowest it has been since 2009.

These loan officer opinions correlate pretty closely, also recently, with the actual trend (lagged) in C&I loans (including the ominous surge in them just prior to recessions).

In 2019, companies once again had retrenched back into less borrowing and less building (and less hiring) despite constant assurances the economy was booming because the labor market was so damn tight.

Why?

Twenty fourteen. Everything changed.

As I wrote recently:

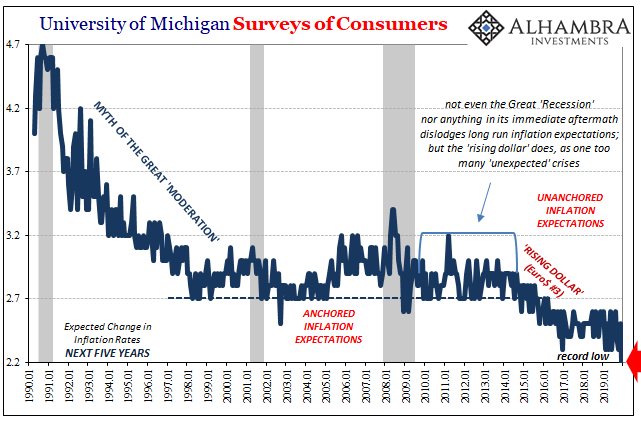

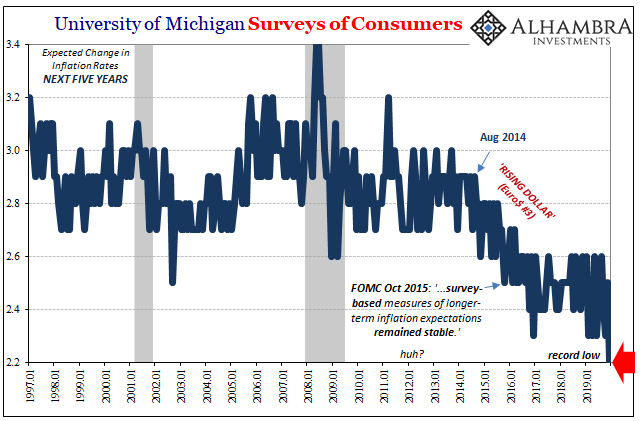

The unemployment rate says the economy is booming, and so everyone says the word boom out loud and nods along in agreement with Jay Powell all the while expectations, along with bond market, show how deep down they don’t really believe it.

In a word: Japanification.

And that word is wholly inconsistent with “secular stagnation” and R*. These are macro things. Japanification is, at its root, what the Japanese have called the “deflationary mindset” which in reality is nothing more than constant QE’s and overactive central banks proving time and again they have no idea what’s wrong or how to fix it. The deflationary mindset is when the population has enough evidence to know in their hearts we’re all stuck.

What really created Japanification in Japan was too many false dawns. The Japanese people, despite constant assurances and reassuring genius monetary policies, became conditioned to expect instead nothing else.

Time and time again; chart after chart. Twenty fourteen. That’s when it dawned in America. Like Japan in the nineties, one false dawn too many.

Supply side factors. Inflation expectations. The dollar. Eurodollars.

Once the eurodollar system erased all possibility of an actual recovery, suddenly R* and “secular stagnation” become more and more popular among policymakers. Rather than look inward for answers, they blame outward lacking any.

No one will say it, but this is in every way worse than the Great Inflation. Inflation, at least, is momentum and movement. This 21st century version of deflation is the antithesis of those. Dullness. Deadness. Hell.

At least in the 1970’s there was action and activity. This version is where the economy is simply frozen. In Dante’s Inferno, Hell is not hot, it is increasingly cold as each layer is further removed from God’s true warmth. Heat is passion and life; cold is where living is further stripped away toward the inanimate. The bond market is making that same journey, if not in a straight line, further into the lower reaches as the economy grows colder and colder.

Who or what could ever be responsible? Is the economy broken, like Jay Powell and R* guru John Williams says? Or, do Economists and central bankers have no idea what they are doing, and the economy is stuck bearing the consequences of their ineptitude?

There is no historical precedence nor template for a broken labor force hooked on opioids becoming far too lazy to go back to college to learn to code. There is, on the other hand, numerous even plentiful historical accounts of central bankers screwing everything up – and blaming everyone else for it.

Those accounts even show how they can get away with it for incomprehensibly long periods of time, too. The Great Inflation lasted at least fifteen years (1965-80). It took nearly two decades and a second world war to finally escape out from under the Great Depression. Japan is still Japan thirty years (and 24 QE’s) later.

Secular stagnation is the right idea about what’s going on, the wrong idea about why, and therefore the wrong name for it. If we are going to label this sucker properly, it has to embody, like the seventies term stagflation, the duplicity and contradictions that come with the official avoidance of common sense and facts.

No one needed Arthur Burns’ confirmation over how inflation was out of control. The Japanese didn’t require Masaru Hayami to tell them they had lost a decade. In those cases, at least central bankers acted honorably if incompetently.

Over the last decade, though, very different story. The idea of recovery itself has be recast and repackaged into something which before 2014 (let alone 2008) would never have been associated with it.

This is the Booming Depression.

That would be the only benefit to a recession showing up in 2020. Without one having been declared since 2009, this is the only reason they’ve been able to get away with calling this depression a boom. A record expansion. It’s so laughable, as if the NBER’s cyclical declarations are all that matter.

But that’s the true significance of 2019 as far as the economy goes. Still one more false dawn to further prove two things: the Booming Depression; and, some things never change, meaning how they really have no idea what they are doing.

Stay In Touch