For the second time this year, the PBOC has today affirmed Chinese banks are offering a lower benchmark loan rate. The Loan Prime Rate was reformed last August just in time for the monetary authorities in China to make it seem like they are being removed from the decisions. And in time for rate cuts to begin, too.

What is the LPR? It is, supposedly, the weighted average rate (after throwing out the highest and lowest) at which eighteen of China’s designated banks will lend to their best customers. They all submit their monthly quote to the central bank which then compiles the panel, tabulates the results, and publishes the single benchmark.

Here’s what I wrote about it last August when it was rebranded and unleashed:

The Peoples Bank of China had always been reluctant to let banks decide deposit funding for themselves. A relic of old Communist thinking, there had remained anxieties and opposition about what could happen when banks “compete” for deposits. Authorities feared an out-of-control bidding war and therefore an out-of-control interest rate and monetary environment.

China’s deposit rate infrastructure was perhaps the last mile on the long road to market reform. In March 2015, the ceiling was abruptly changed, moved to 130% of the benchmark. Two months later, 150%. In late August, the PBOC announced that the interest on term deposits of longer than one-year maturity would be uncapped. Finally in October 2015, the ceiling was scrapped for all deposits.

When the central bank let the long-term deposit rate float, it said, “This marks another important step forward in interest rate marketization reforms for our country.” The timing, August 2015, was shall we say curious. You might remember that particular month for other reasons.

Or, what better way to “demonstrate” monetary easing is easing than to have what is meant to be a bank-derived lending rate follow along an underlying predetermined course. No one but China’s central bankers really knows what rate the 18 banks quote.

Yi Gang says he is easing and here’s his “proof.”

According to the revamped guidelines, the chosen 18 (the list was increased last August to include eight small and midsized banks in addition to the ten large institutions that had made up the panel going back to October 2013 when the LPR was first conceived but rarely used) must link their submissions to the rate charged by the central bank’s medium-term lending facility (MLF); thereby creating what is essentially a spread merely “influenced” by the PBOC before being confirmed by these banks.

The MLF rate went unchanged today though the LPR was reduced (by 20 bps for one-year loans, and by 10 bps for five-year terms). Is credit becoming easier to obtain in April 2020 because of effective policy easing and accommodation, or do PBOC officials want you to think that it is?

In either case, it hardly bodes well for the probability of a global “V”, a scenario which will require China’s economic lift. Had policymakers any confidence that this is all about the non-economic shutdown and how it will leave no lasting scars, what need for convincing all of Chinese lenders, global markets, and the already optimistic Western financial media of more “stimulus?”

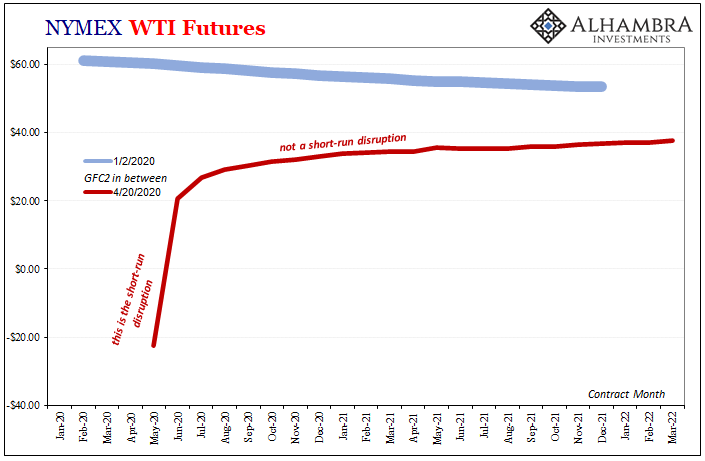

Basically, what we are seeing in oil markets today. The chaos in the short run is garnering all the headline attention when it is, in fact, the back end of the oil futures curve that should be scaring the living daylights out of you.

It’s obviously quite easy to understand why WTI as low as -$40 (that’s not a misprint; oil is deeply negative in trading today) May 2020 oil delivery should grab everyone’s notice. A bit harder to realize, as the June 2020 contract is pulled down toward $20, that the market is putting the global economy on notice as to how there’s a lot more than a non-economic shutdown to consider.

Settle in, this sucker’s not going to be a one-and-done.

Once the front-end chaos is eventually cleared up, which it will be, then what? More and more, it’s not the contours of a “V” that are becoming visible just over the near-term horizon. There’s a long road back – at best – which increases the risks GFC2 follows along the same way as GFC1.

As bad as GFC1 had been, it was its aftermath which cost the world by far the most. We were still dealing (trying to) with the repercussions a dozen years after the first global dollar eruption in August 2007.

And thus, why the PBOC might also be interested in raising the stakes on crediting itself with unverifiable “market” successes. After all, Chinese banks have been recognizing this “easing” going all the way back to August 2019. China’s economy, like the world’s, was experiencing increasing trouble long before Wuhan.

Stay In Touch