He called it “unfair competition.” That’s one way to describe it, surely not the proper way. But who could blame the guy? After all, these were not normal times though at the time hardly anyone had yet realized it.

James J. Davis was the second person to hold the title Secretary of Labor. Appointed by Warren Harding, he began his tenure in March 1921 and would ultimately serve three American Presidents (Coolidge and Hoover both kept him on), a feat still unmatched.

Shortly before the end of his time in the Presidential Cabinet, in September 1930 Secretary Davis was as optimistic as almost every other expert and leading businessman. Depressions, even bad ones, these were cyclical in nature. No matter how far down, there had always been a way back up usually in quick succession once reaching bottom.

He wrote that the economy in the late Summer of 1930 was definitely on the upswing, “unquestionable signs of life” in all corners.

What was keeping the recovery from leaping forward out of the doldrums, he reasoned, was this “unfair competition” among businesses that was “ruining business of the country by forcing men to sell under cost of production.” The result of which, mass unemployment. If prices are discounted so far, there was little left for any businessman whether strong or weak to pay workers.

It was what would shortly thereafter be classified as monetary deflation. And John Maynard Keynes was right about it being by far the worst of the evils. As Jim Davis was only beginning to reckon at the twilight of his lengthy labor career, inventory discounting and liquidation, companies so desperate to recoup “liquidity” they have to sell at almost any number just to raise cash.

Surviving the short run becomes all that matters on the ground.

In doing so, the lack of money leads to a gross devaluation of all production (which includes services). The systemic worst of all worst cases.

This is the classic monetary deflation of scholarship, more above the “deflation” we often speak about in today’s terms. I’m as guilty as anyone, if not more so, of using the term a little too loosely to fit our current age. Commodity price deflation as a result of Euro$ #3, for example, doesn’t really go far enough.

But it could if the resulting economic contraction and scramble for dollars leaves such overcapacity and desperation for liquidity in the business and financial sectors. Once that happens, past some unknowable threshold, true deflation takes hold and it can only end up in the labor market (as Keynes recognized).

I want to be careful here and stress that I’m not suggesting we are in any way in the same deflationary ballpark as 1930. While that’s the good news, the bad news is delivered to us from Markit today in the form of its final manufacturing estimates for the month of April 2020. The whiffs of the bad stuff are becoming just a little bit more noticeable.

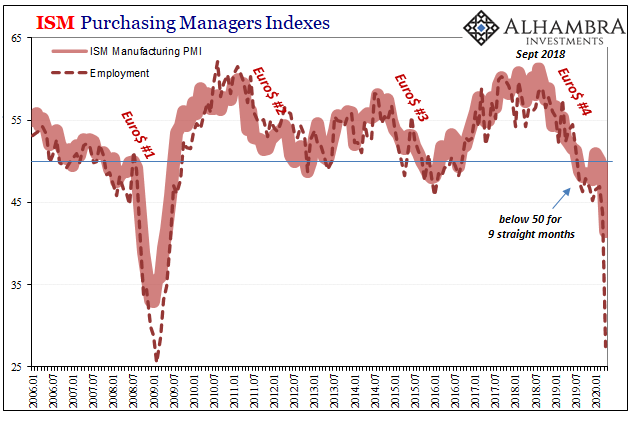

Spare capacity across the sector and pessimism about the year ahead meanwhile resulted in the fastest fall in employment since March 2009, despite efforts to furlough staff. Both input costs and output charges fell sharply as companies and their suppliers offered discounts to boost sales.

Again, this isn’t 1930-33 levels but it is beginning to look like the same kind of thing, a serious fracture in the economic system which extends beyond the first order effect of the COVID-19 shutdowns.

I maintain the reason for its quick and easy, dastardly appearance is that original sin officials made right from the start. The economy everywhere was in poor to troubling shape to begin this thing.

Counting on it to have been seriously strong as the unmovable rock to stand on while the non-economic storm raged past, more and more it seems as if this could go down as the biggest mistake. Existing fragility.

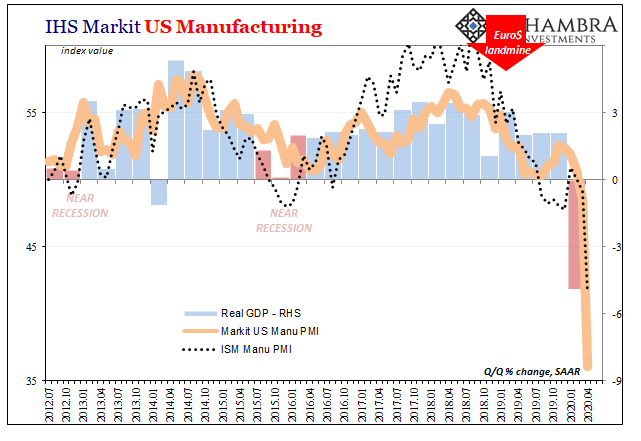

While IHS Markit’s Manufacturing PMI was revised down a little more to 36.1 (from a flash estimate of 36.9), the actual pace of the current downturn is more determined still. These PMI’s are a bit funky in that with so little business, supplier delivery times have shrunk which gets added on to the headline number.

The underlying condition away from these quirks might be better represented by the latest figures from the ISM. Its Manufacturing PMI estimates, released today, functioning largely the same way: an artificial 41.5 for the month of April 2020.

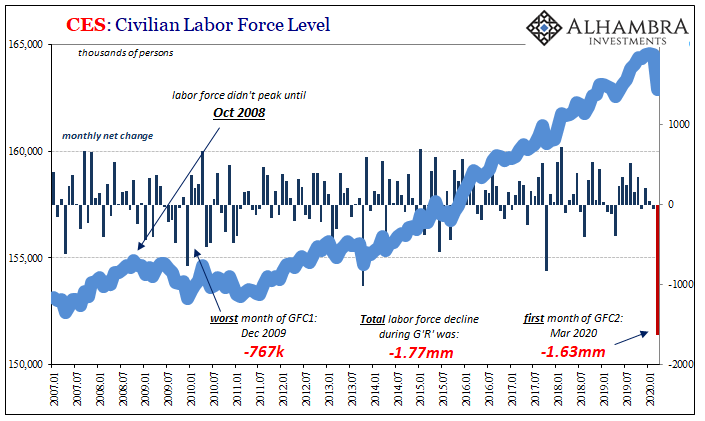

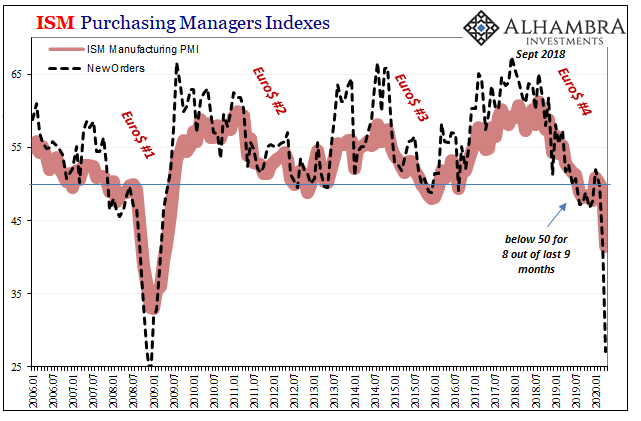

While still the lowest headline since 2009, the New Orders index dropped to 27.1 while the component for employment collapsed to 27.5. These are, of course, already among the lowest in the series’ long history.

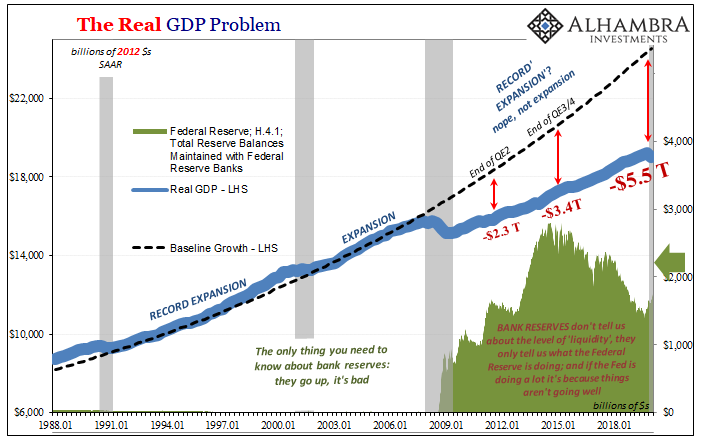

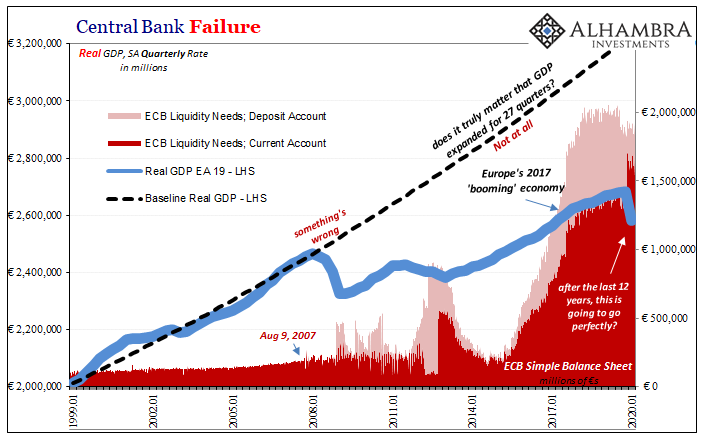

Apart from the stay-at-home orders, economic weakness was obvious in these figures for months beforehand. Manufacturing employment, according to both the ISM and Markit, has been weak to contracting ever since last summer; Jay Powell’s rate cuts, not-QE QE5, and “repo” operations all making no difference.

The same was true in manufacturing orders, despite one outlier increase (result above 50) in January. In short, the US economy had been struck by a very deliberate downturn and manufacturing recession going back to the end of 2018 (again, the bond market nailed it). This turned more serious by mid-year 2019 (thus, the inverted curves and recession “scare”) and then stuck around for the start of 2020.

Just in time for the coronavirus pandemic.

I’ll go back one more time to what I wrote yesterday (published today):

No one is downplaying the severity of the situation, even the worst offenders deserve some limited credit here. Where they’ve offended is in overplaying both the starting position and then their ability to limit the downside and pick everything back up on the other side. In between is not really the issue.

We’re only getting data on the first part of it, and already it’s enough to make you sick. They bungled 2008, badly. They botched everything about the last two years. And now the first steps into the current crisis couldn’t have gone worse.

If the coming second order effects (especially those derived from the first order effects of GFC2) include classic deflation, then that’s a result of the economy like the monetary system being fragile and weak from the very start.

And it argues not for a replay of 1931, we can’t know what it will look like until we begin seeing these second (and third) order effects up close, for now all it portends is how you might be wise to shelve your hopes for the pain free “V.” There would be, will be, a whole lot of negative forces for that kind of recovery to overcome.

Which is exactly what central banks are for, which only further means forget about it.

The good news, if you want to see it, is that “L’s” can look a lot of different ways; they don’t necessarily have to be what Secretary Jim Davis faced. But they aren’t painless and they do punish.

Hopefully this time the punishment will include some accountability toward the top.

Stay In Touch