Anna Jacobson Schwartz often gets buried under the mountains of study Milton Friedman conducted on his own. Contrary to what some, perhaps many, might think, Friedman didn’t write A Monetary History by himself. Anna Schwartz was his co-author for what would become one of the most important volumes of economic scholarship of the entire 20th century.

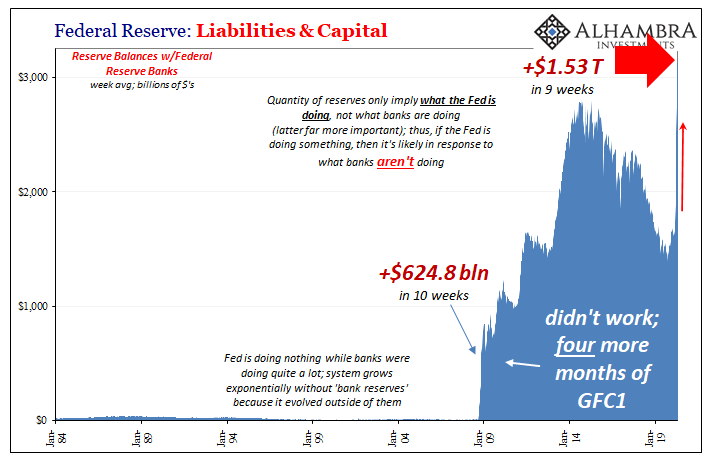

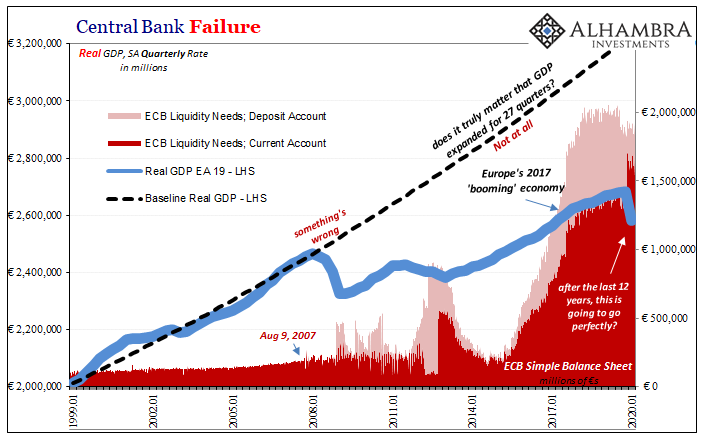

Pretty much every central bank in operation today lifts its policies directly from the book’s pages. Quantitative easing sounded new and radical when it was introduced to Americans by then-Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke late in 2008, but not only had it been tried (and failed) in Japan earlier in the same decade Friedman and Schwartz had written about monetary policy “bond buying” all the way back in 1963.

And yet, among Bernanke’s most vocal and personal critics was Milton Friedman’s co-writer. Penning a searing op-ed in the New York Times in July 2009, the Global Financial Crisis still fresh in everyone’s everyday senses, Dr. Schwartz charged:

Mr. Bernanke seems to know only two amounts: zero and trillions. Before 2008 there were only moderate increases in the Federal Reserve’s aggregate balance sheet numbers, but since then the balance sheet has exploded by trillions of dollars.

You could count her among the growing chorus of critics who were deathly certain runaway inflation had already been baked into the monetary cake. Bernanke had overdone it, she said, and the US would pay for the mistake with another inflationary fireball.

None of them, however, reconciled this explosion in “money printing” with another half a year of continued crisis even after that jump had been begun. [I’ll save Paul Krugman’s IS-LM liquidity trap version for another day.]

She wrote the essay to oppose his re-nomination as Fed Chairman on the grounds he’d gone too far.

Schwartz was hardly alone. Three months before her, Martin Feldstein, the influential leader of the influential NBER, wrote in the pages of London’s Financial Times how inflation was looming on America’s horizon. In fact, that phrase was used as the title for his article, where he predicted that the combined efforts of the Obama Administration (fiscal deficits) and the Federal Reserve (Bernanke’s QE) would certainly lead to uncontrolled consumer price appreciation:

But now the large US fiscal deficits are being accompanied by rapid increases in the money supply and by even more ominous increases in commercial bank reserves that could later be converted into faster money growth. The broad money supply (M2) is already increasing at an annual rate of nearly 15 per cent. The excess reserves of the banking system have ballooned from less than $3bn a year ago to more than $700bn (€536bn, £474bn) now.

It didn’t matter that the predicate forces of deflation had re-emerged in 2010. Once Bernanke attempted to counteract them with QE2 late in that same year, the highly distinguished experts of the so-called E21 group famously published its letter to him demanding that he stop before it was too late.

The planned asset purchases risk currency debasement and inflation, and we do not think they will achieve the Fed’s objective of promoting employment.

Why had Bernanke been led to believe a second round of QE was necessary in the first place? Because it was such potent money printing it had to be repeated? Instead, not long after, beginning in the middle of 2011 (Euro$ #2), the Federal Reserve would end up trying to dismiss a 5-year stretch undershooting its inflation target (implicit before March 2012, explicit thereafter). And the dollar? Up, up, up, and away.

None of the predicted disasters ever came to fruition, including those which surmise US Treasury prices must be heading toward zero along with the plummeting dollar and skyrocketing consumer prices. How can we sit upon the opposite of so much of this currency “debasement?”

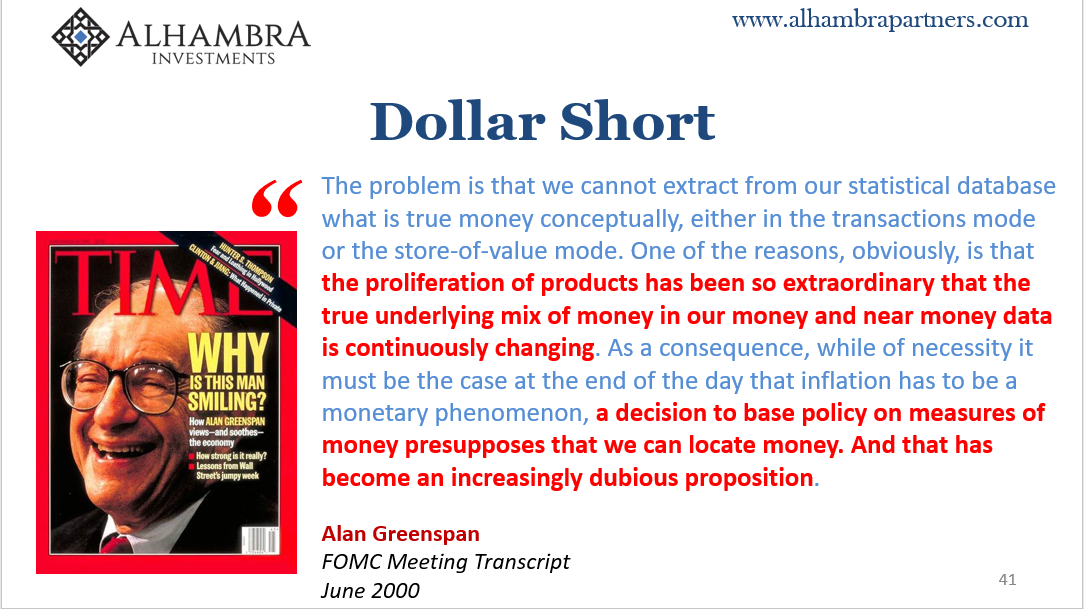

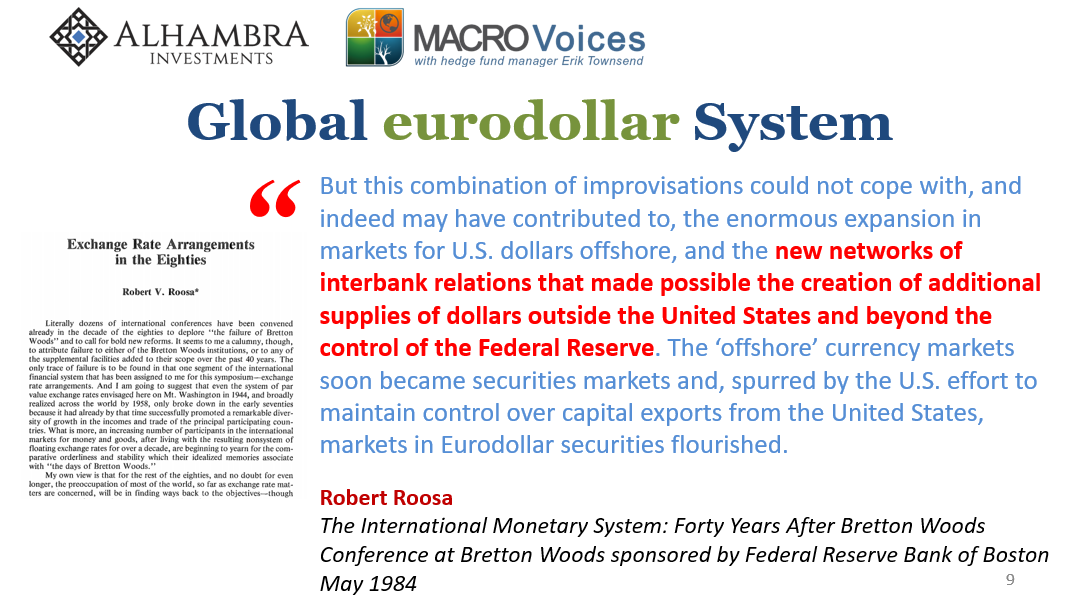

It’s as if something big had been missing from these monetary calculations; including those made by Anna Schwartz, co-head of the entire monetarist discipline. As if between 1963 when the book was written and 2007 when the system finally needed to lean on it, the monetary system itself had been rendered wholly unfamiliar to its writers and all who followed them.

Alan Greenspan had confessed that much throughout the speeches he gave and the discussions he held in the nineties and beyond. Even Bernanke, who TIME Magazine ignominiously awarded with their 2009 Person of the Year title, had been forced to admit, numerous times, that there was always more going on than he could ever put together.

None of us appreciated what a jury-rigged thing the financial system had become. Of course there were things we could have done better, but this was a perfect storm.

In giving him their highest acclaim, the magazine noted that Bernanke had been pushed by extreme events to completely “reshape monetary policy.” Maybe that was because he didn’t know what he was doing. “Reshaping” is something that would’ve been particularly useful had it taken place before the crisis, don’t you think?

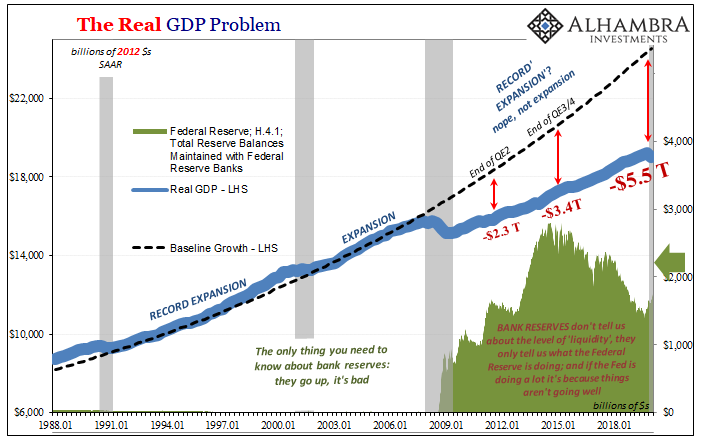

What critics all fear, and what Bernanke and his supporters all love, is bank reserves. The explosive increase is to the former a curse and a future evil while to the latter the world’s salvation. The disastrous truth lies in the middle, united by what both sides get very wrong.

There’s nothing particularly useful about bank reserves; no one can hold them in their hands, nor can any person or business have them in their accounts. Yet, they are treated as “base money” why? Tradition and inertia are not sound reasons to begin with, let alone given the dynamic world which we inhabit.

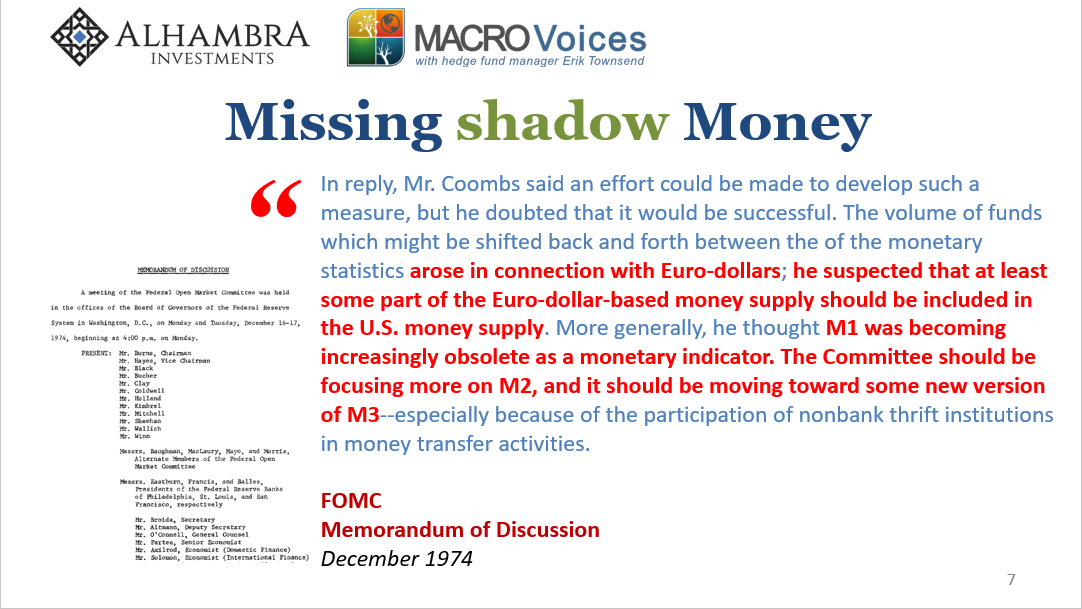

The concept of such base money was invalidated more than half a century ago, only it was done in secret or, where in public, with as little fanfare as possible. Ironically, when the Fed discontinued M3 early in 2006 the central bank was accused of trying to hide inflationary money.

Now, everyone can see what they think is the “money printing” but no one can find the inflation.

Whether the monetary system was being inflationary or not, they couldn’t have told you one side or the other. That job had been turned over to the federal funds target, and at that particular time Alan Greenspan was having his “conundrum” about what role it exactly played in this system. Neither he nor his disciples would choose to consider the alternative staring them in their face (the central bank isn’t central; on the narrow issue of bond yields and interest rates these are determined by a global dollar market rather than the central bank and its policies).

Just before M3 was discarded, in November 2005 Bernanke traveled to Europe where he recognized the substance of the disturbance if not, obviously, given what unfolded less than two years later, the potentially grave implications:

In 1960, William J. Abbott of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis led a project that resulted in a revamping of the Fed’s money supply statistics, which were subsequently published semimonthly. Even in those early years, however, financial innovation posed problems for monetary measurement, as banks introduced new types of accounts that blurred the distinction between transaction deposits and other types of deposits. [emphasis added]

That kind of blurring wasn’t a one-off; innovation of this type, including repo throughout the Great Inflation of the seventies, would continuously alter the monetary order. If Ben Bernanke was going to really reshape monetary policy to make it monetarily effective, he would’ve been wise to have done so long before August 2007.

He just didn’t think it was necessary. The central bank didn’t need to define money because so long as everyone believed the Fed Chairman was a monetary Santa Claus bearing gifts of base money there’d be no other requirement of monetary policy (expectations policy).

Fed funds, bah.

Notice who was at the center of this monetary revolution even as Bernanke told it; not the central bank, but the banks which were conducting all the monetary experiments in the real economy and therefore driving all that transitionary distorting. M1 and M2, as the FOMC would note in the early seventies, were made obsolete by who does matter in this pecking order.

Bank reserves are, therefore, little more than one form of account the banking system might hold. They are not money in any meaningful sense. They are possibly money only in that if a bank or banking cohort wishes to use them in a meaningful way.

But that requires the right combination of balance sheet factors (the real money in this global system) in order for it to happen. Unless animated by the banking system, bank reserves, no matter at what level, are inert. They come off Bernanke’s printing press that way and remain in this condition so long as those bank factors say so.

Not much more useful than a laundry token (as Emil Kalinowski likes to say).

This explains both sides of the QE divide (which, then, isn’t really a divide at all). The inflation critics don’t factor balance sheet constraints in their view of this outdated “base money.” Neither do central bankers, which is why they expect bank reserves to be equivalent to “liquidity” at the least. To the latter, laundry tokens are a command to the banking system from Santa which, in theory, is always beloved and obeyed without question.

Thus, the central bankers think QE will be effective but not inflationary while the critics all think it will be over-effective and very inflationary. Neither want to concede the reality. So long as the real monetary stuff of the banking system reigns supreme and independent, the long-ago financial innovations banks came up with for the real economy, QE won’t be either of those.

Here in May 2020, it’s as if none of this had ever happened. Once more the financial media fills with regrets that Jay Powell will become too successful with all his “money printing.” In combination with President Trump’s flirting with a $4 trillion deficit, hyperinflation here we come!

The dollar will surely plunge to zero, they’re saying again, Treasuries are definitely going to get priced in the same range, and consumer price inflation is guaranteed to be on par with Weimar Germany. How could it end up any other way? Didn’t you see the $1.5 trillion!!

In other words, there’s this sense that authorities risk taking these (ineffective) rescues too far. And while that could be true, it won’t matter in the realm of the monetary system. Why? Because authorities don’t get to decide where that line is.

The banking system does. So long as it does, and so long as it remains detached in this manner, the only risk is the one we’ve been stuck with ever since August 2007. The same one that was just handed another “L”-shaped boost, a second GFC-level deflationary mistake. No matter what level of bank reserves, global dollar shortage.

That’s the thing about laundry tokens. Other than exciting even the most credentialed and honored critics, they don’t actually do much outside the laundromat. Japan 2001. America 2008. Japan 2013. Europe 2015. Do we really need more proof? Yes, because Economics is an ideology.

Stay In Touch