It was another one of those good news, bad news data days in China. Unfortunately, the good news just doesn’t make much sense. That was Chinese exports which, according to the country’s General Administration of Customs, increased by 4.5% year-over-year in April 2020. Given the state of the world last month, exports were expected to drop by 12 to 14% (depending on who you asked).

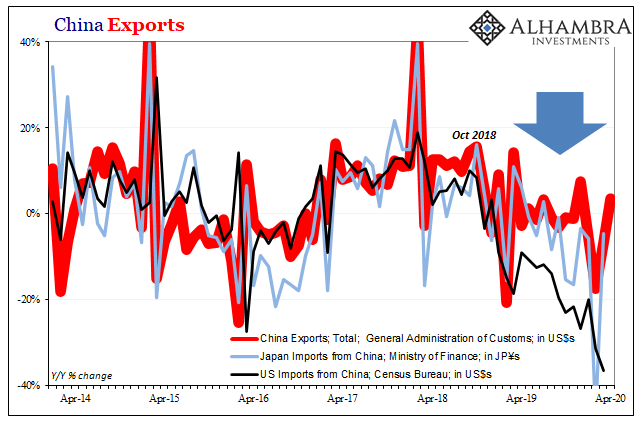

Like the last couple years of the US unemployment rate, increasingly China’s trade data finds itself in isolation without corroboration. What goods leave its borders have to arrive somewhere else, primarily the United States and Japan. Therefore, if the Chinese estimate one level of exports heading to either of those we should find, within some margin of error, the same or abouts in the place where they are scheduled to arrive.

Going back to October 2018 yet again (the landmine), that’s increasingly not the case. China’s Customs Administration isn’t going nuts suggesting that the export business is thriving, but it isn’t matching up with the serious weakness its partners figured this globally synchronized downturn was leaving the global economy.

China’s export data is weak, near-zero. Japan and the US are saying it should be well below.

Notice how up until late 2018 both import estimates from Japan and the United States line up pretty well with the Chinese. Since, Japanese import figures have been slightly weaker (data in yen) especially February 2020 while US data is in a different world from China.

Some have proposed that in order to get around tariffs and trade restrictions, the Chinese are re-routing goods through intermediary countries; meaning that overall exports heading out from China on this more circuitous route are relatively constant even if the United States shows a huge drop from what’s on paper originating in China proper.

While that’s undoubtedly true for some proportion of US-China trade, the Chinese Customs agency actually says there’s been barely any slump in exports directly to the United States. Combined, for the first four months of 2020, the Chinese indicate they’ve exported 1% more into the US than they did in the first four months of 2019.

In March, they claimed the accumulated export total heading this way was +0.4% bigger for the first three months of this year compared to last year. Not a huge windfall, to be sure, but that’s not at all what the American government shows.

The US Census Bureau, on the contrary, puts US imports from China at an accumulated -28.4% through March (the latest American estimates). This isn’t a margin of error kind or error. These are categorical differences.

The numbers are somewhat closer with Japan, as shown above, but still some distance.

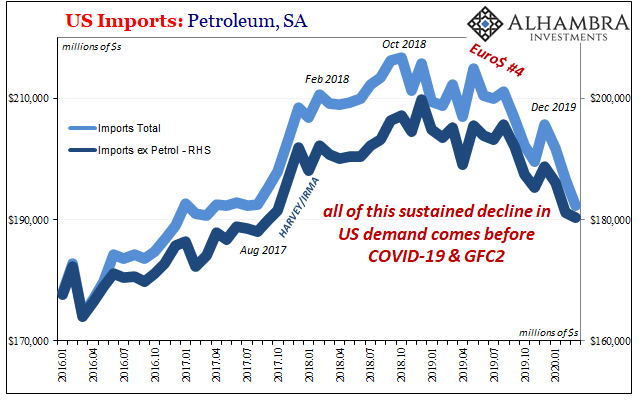

If China’s export economy, while not exactly thriving if it is treading water at least as the Chinese numbers suggest then where are the goods ending up? They aren’t coming in to the US due to a combination of tariffs and weak American demand (the huge slump in total imports which began long before COVID-19, too). And China’s production isn’t ending up in Japan, either.

So, if Chinese exports seriously outperformed all reason and expectation in April, is it real good news – or the manufactured kind?

There’s a big and as-yet explained discrepancy somewhere.

That’s a bad-news segue into the real bad news which was China’s imports. Questions surrounding these numbers, too, though maybe put to rest in April’s data. Year-over-year, imports crashed by 14% after falling by just 1% and 4% in March and February, respectively. The latest estimate is the biggest decline in four years, going back to January 2016.

December’s outlier pop has quickly dissolved as last year’s hope gave way to a much harsher reality. At least for inbound trade.

But then why the difference and the possible goosing of the export data? If you’re going to cheat, why not cheat on both sides? Some real 4-d chess-playing going on here?

Obviously, no one’s going to get any answers on this, not from the Chinese, anyway. Leaving the data open to interpretation instead, you can choose to believe the good news, the questions surrounding it, or the bad news. Maybe that’s the point?

Stay In Touch