Trading partners like Mexico didn’t have a labor participation problem by which to hide the economic downturn last year. The whole idea of “decoupling” in the 2018 sense of the word was how the US economy, by virtue of its 50-year low unemployment rate, couldn’t possibly be as weak as it increasingly appeared overseas.

The US was good, they kept saying. If there was a problem it was China. And Germany. South Korea. Japan. South America. All of Europe. Mexico, too.

The truth was more straightforward: last year did not go well for anyone, anywhere. That’s the thing about this globalized economy. There aren’t discreet parts which become immune from economic (meaning monetary) diseases cropping up in the others. Like the coronavirus, what goes wrong in one place soon spreads and infects the rest.

The only differences are to what degree and in what order.

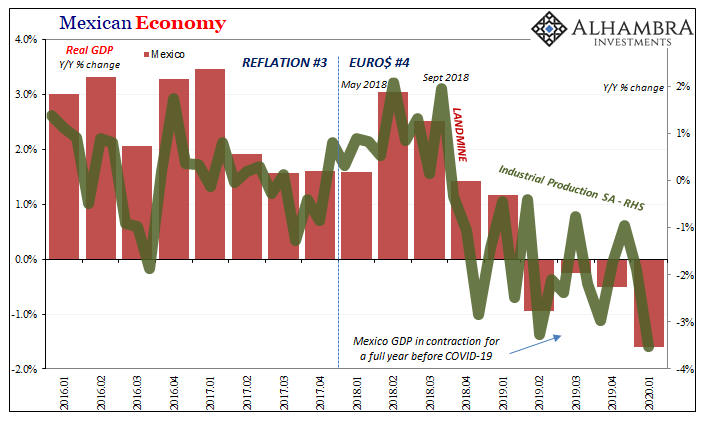

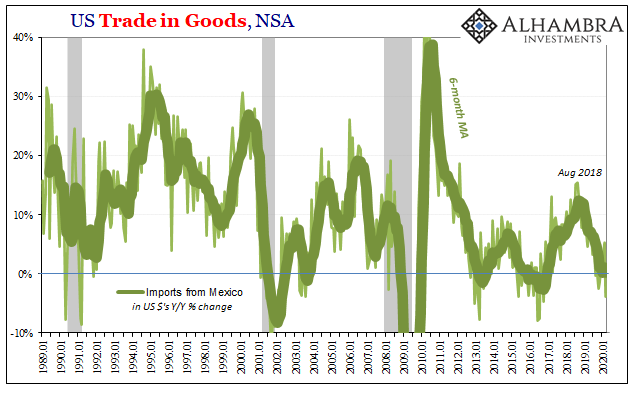

Take Mexico, for starters. It’s difficult to (honestly) argue that the US economy must be booming if our biggest partner to the south has been in recession for nearly a year. Mexico can and certainly has exhibited its own negative idiosyncrasies before, but the major pull of all these economies is global.

That’s why Euro$ #4 shows up in every single chart in any country around the world at almost exactly the same time. The sync in synchronized.

More evidence to pile up onto the mountain backing up the bond market’s view of late 2018. For all of last year, the Mexican economy had been contracting – and not just contracting, but consistently in a manner it hadn’t suffered since 2008-09’s Great “Recession.”

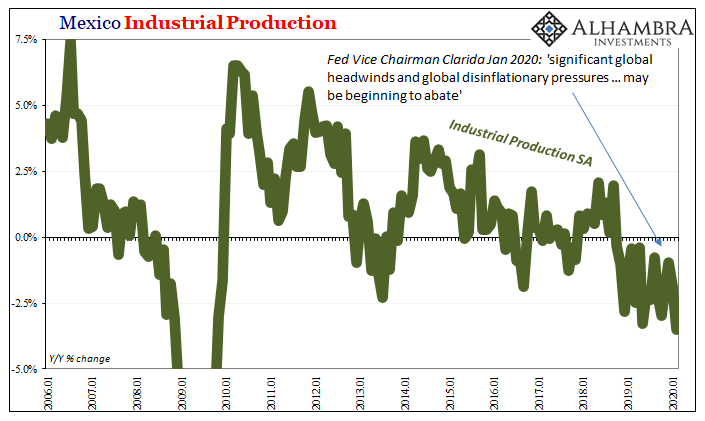

The nexus of that suffering emanated right from the country’s industrial heartland, and in the same fashion as other global trade bellwethers like Germany and Japan.

The world had been warned years ago:

The bond market told everyone throughout 2018 globally synchronized growth wasn’t happening, and that there was far greater risk of (renewed) deflation and downturn due to monetary breakage than there was of inflation and growth acceleration of the kind which would have (conveniently) vindicated the last three Fed Chairmen.

Flat and inverted curves all over the place by 2018’s end, guess who won that argument a long time before COVID-19?

In short, Mexico demonstrated all-too-well how the world was in very serious trouble throughout 2019. Contrary to what Jay Powell and his group tried to claim at the end of last year, there was nothing solid to indicate the situation had gotten any better as 2020 opened up. Instead, there were far more suggestions of the downturn growing worse.

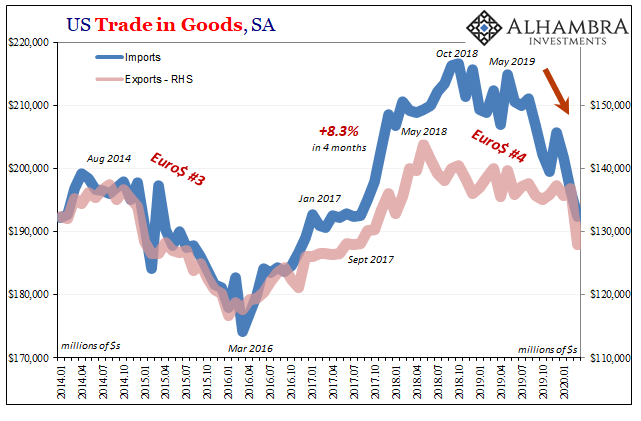

That possibility echoes throughout US accounts, too. You can dismiss what had already become a manufacturing recession for reasons more broadly related to a services-based economic system, so while one doesn’t necessarily mean a full-blown cycle is underway this sustained goods economy downturn is still a substantial argument for serious weakness.

If a core sector is struggling to this degree no matter what, that’s very strong signal for the opposite case from a strong economy.

US factories like their Mexican counterparts had been in retreat dating back to the same turn in September 2018 (landmine beginning October 2018 which, again, the bond market immediately picked up; unlike Jay Powell who was still hiking and the financial media still cheering him on).

In March 2020, according to the latest estimates from the American Census Bureau, orders at US manufacturers (of all kinds) fell by the largest monthly amount (seasonally adjusted) on record (-10.3%). The only comparable monthly decline was a 2014 quirk due to Boeing orders. The worst month during the Great “Recession” had been November 2008 (-7.7%).

What this data shows, like other figures, is that the decline was well-established before 2020 began, continued through January and February of this year until March when the system seems to have buckled.

Just folded up like the cheapest of suits when commentary surrounding this “strong” US economy was ginned up as if the unemployment rate would be the foundation from which the recovery was going to be built upon.

It’s an uncomfortable reality which is further driven home by the rest of the US trade figures supporting the factory data. US exports to the rest of the world finally showed up in the deep minus in March. Exports had been on a slow burn downward since the middle of 2018, unlike imports which had continued climbing until the landmine.

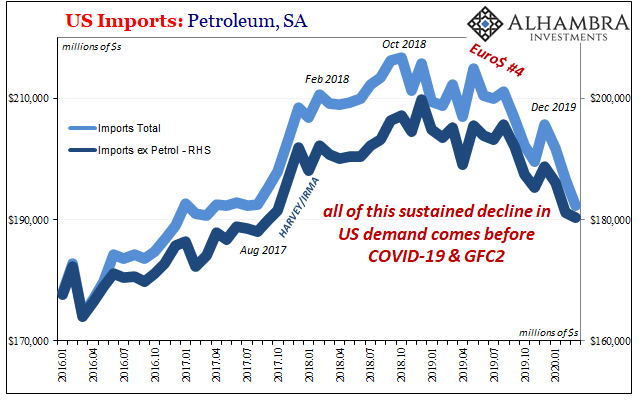

But that just meant US demand for foreign-produced goods, like those made in Mexico, had been more deeply disturbed following Q4 2018. Throughout 2019, it was weakness in American demand which had been most apparent and pressing – therefore the recession “scare” 2s10s curve inversion by August – heading toward the final months.

That didn’t change, as another key piece of evidence contradicts Jay Powell’s notion of a year-end turnaround. As we see in Mexico, Japan, Germany, etc., if anything, the globally synchronized downturn accelerated in the first few months of 2020 before the most extreme forms of COVID-19 “mitigation” were brought up.

That’s why so much data ends up in sync; and not the way 2017’s bumper sticker slogan had you believing. US imports, US factory orders, ISM sentiment, Mexico’s economy, and all the rest. This year is shaping up to be an “L” in large part because of problems that showed up, and were decidedly obvious, years ago.

Euro$ #4 was a huge problem and a key reason why there was such a violent reaction (GFC2) to the negative economic and financial prospects raised by March 2020. The entire world economy was in such bad shape, in many ways as bad as it had been since 2008-09, and somehow central bankers and politicians managed to convince most people they had it all under control.

Worse still, that message somehow still resonates widely.

I’ll reiterate again:

No one is downplaying the severity of the situation, even the worst offenders deserve some limited credit here. Where they’ve offended is in overplaying both the starting position and then their ability to limit the downside and pick everything back up on the other side. In between is not really the issue.

We’re only getting data on the first part of it, and already it’s enough to make you sick. They bungled 2008, badly. They botched everything about the last two years. And now the first steps into the current crisis couldn’t have gone worse.

Stay In Touch