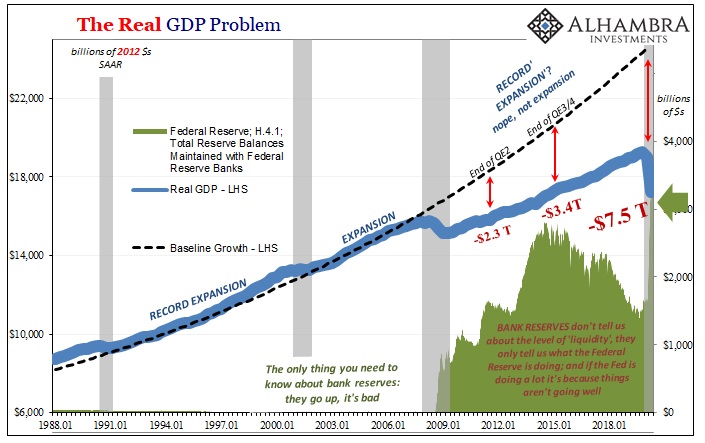

The term “balance sheet recession” is one that had come up more often a little more than half a decade ago. At the same time everyone at the Fed, especially Bill Dudley, was wondering why QE had kept coming up (way) short of every one of its goals, some of them began to speculate about this other thing. If the Great “Recession” had triggered one, then monetary policy would have looked as helpless as it was looking.

What is a balance sheet recession? For one thing, it’s much closer to the truth than everything else the Federal Reserve has cogitated on. Simply put, credit bubble goes pop.

The idea is straightforward enough – before GFC1, the US (and global economy) had suffered a debt-fueled imbalance to an extreme. Central banks don’t favor the possibility because, well, see Bernanke in 2005.

However, regular people unbiased by econometrics and its deeply embedded efficient markets hypothesis knew different. Hints and allegations, as they say, were everywhere by 2005. The US housing bubble was practically undeniable – but that didn’t stop Bernanke and his like

Once the inevitable pop, though, quite naturally people and/or businesses deleverage themselves – a form of basic de-risking after having been shown the downside of aggressive risk-taking. They had racked up massive amounts of debt pre-crisis based on all the common bubble-type rationalizations, so in the post-crisis period they come to really appreciate and internalize the error of those ways.

Good Chairman Ben can lower rates as low as he might want, down to zero, “stimulating” debt in the textbook fashion, but, balance sheet recession, debt will not be stimulated. Deleveraging takes priority even in the face of the cheapest ZIRP credit (in the textbook imagination).

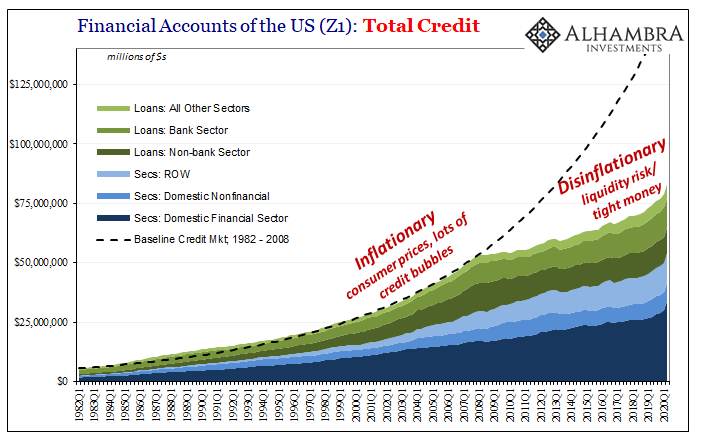

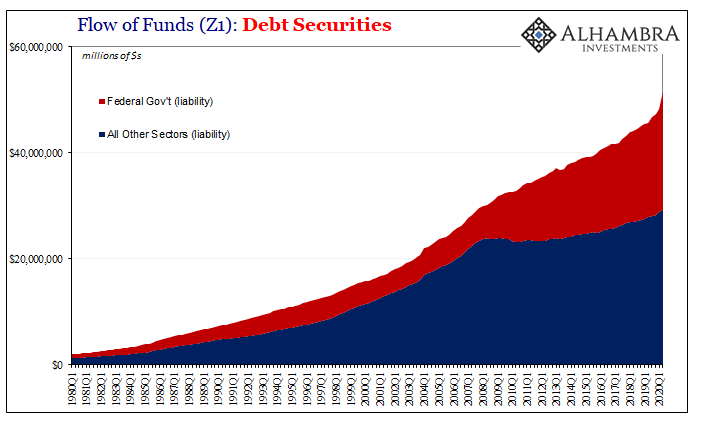

Might this explain, then, what we see above? Too much pre-crisis debt and then concerted deleveraging, the dreaded balance sheet recession?

Given the debt figures alone, it seems a possibility but only up to a point. The main point with this kind of deleveraging is that it doesn’t go on forever. The issue is strictly time. At a certain time, enough debt has been cast aside – paid down or forgiven – and the world goes on, salivating banks (who can’t believe their luck with so much QE “free money” and low rates at the front) get their customers back.

Recovery at last!

Twelve going on thirteen years, however, that seems like enough time to call it. And that’s the primary reason you don’t hear much about a balance sheet recession any longer. It might’ve been possible up to, say, maybe 2013 or 2014 at the latest.

Beyond, where’s the demand?

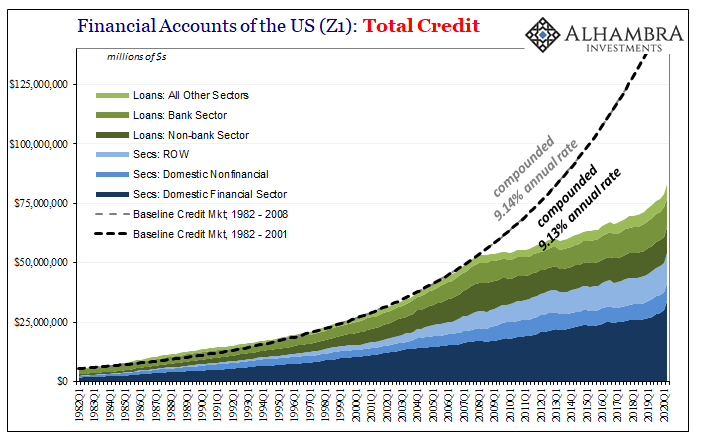

Credit growth was actually pretty stable throughout the pre-crisis period (which makes sense, eurodollar). Thus, playing around with any baseline comparison, using one up to, say, 2001, doesn’t really alter the view. Credit wasn’t so excessive between 2001 and 2007 when compared to 1982 through 2001.

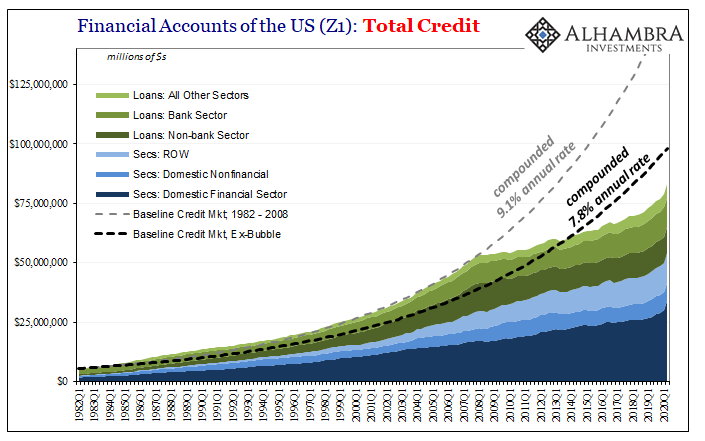

You’d really have to squeeze credit growth all the way down under 8% historically in order to just get a situation approximating what a balance sheet recession might have looked like out to 2014.

While it might not seem like much, the difference between 9.1% compounded and 7.8% compounded doesn’t just remove the housing bubble in the US, it totally rewrites history to the tune of tens of trillions. In other words, placing the “true” underlying non-bubble baseline for the credit market down that much just to push deleveraging out as far as 2013 is wholly unrealistic. And even then, where’s the credit restart post-2014? Never happened.

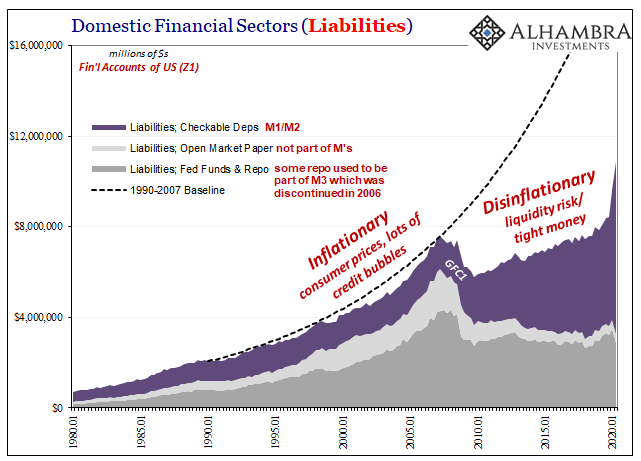

But that’s not even the biggest problem with this idea. A balance sheet recession, deleveraging even to a substantial degree, just wouldn’t produce the kinds of repeated liquidity problems and global dollar shortages we have observed and continue to witness.

That’s because the balance sheet recession begins with the premise that the shortfall is in credit demand, not credit supply. QE and ZIRP, those would have fixed the banks so banks otherwise stand ready to satiate any level of demand (thanks to Bernanke). With low demand, there’s no growth thus balance sheet recession and bank managers are sad.

Deleveraging stops, demand comes back and so does the smile on every banker’s face.

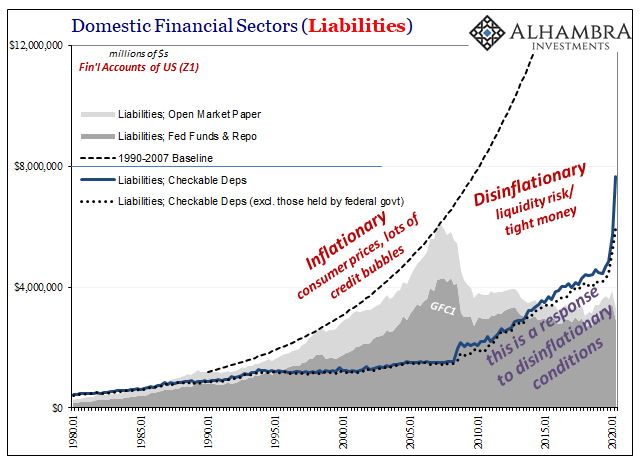

Continued liquidity problems, on the contrary, point the finger at the banking system therefore supply of both money (whatever that is) and credit (often indistinguishable from the concept of money). Banks shrink and de-risk (see below) regardless of demand factors.

Tons of evidence for this.

And this is also where the interest rate fallacy comes back into play; low rates are the consequence of ineffective monetary “stimulus” which is then perfectly consistent with both repeated liquidity events (eurodollar squeezes) as well as these supply side credit factors.

Including time, which now stretches out well past a decade.

That’s not all; in terms of credit demand, the only one truly taking advantage of low rates in reality has been the only one which really can. Another key piece of evidence for the interest rate fallacy, basically the sole source of credit growth (which, obviously, doesn’t even come close to making up for this credit shortfall even factoring a reasonable baseline that excludes the pre-crisis bubble levels) has been the federal government (as well as other sovereign issuers around the world).

Banks won’t lend to anyone else, but “somehow” they sure do love their UST’s (yet we’ll continue to hear about how there’s “too many”). Balance sheet recession? No. Liquidity/money problems? You betcha.

And it becomes a self-reinforcing cycle, the very one the central bank exists to break the economy and money/financial system free from – if instead of fairy tales about money the central bank actually did money in the way the textbooks all claim.

With federal government borrowing the largest additional credit source to the economy, it is also the least economically efficient method which only adds more to negative factors piling up against legitimate growth.

The more only the government can borrow, the more only the government does borrow. And the more the government does borrow, the harder it is to get the economy growing (sorry, Krugman). The more difficult it is for meaningful growth, the more banks will only lend to the government.

And so on.

A balance sheet recession might have explained only one set of facts and only up to around 2014 at the latest; at some point, widespread demand for credit should’ve kicked back in and the banking system immediately meeting it. And 2014 was the perfect time for it, too – recovery stuff, including, as you might remember, the best jobs market in decades.

Instead, the only way to explain all the facts, including both time and repeated liquidity cycles, as well as, obviously, a thirteen-year long (and still counting) deviation in economic growth worldwide, is chronic eurodollar system problems. And it’s not like we have the slightest trouble finding evidence for them.

Stay In Touch