What the hell is a bank reserve? Is it money? Since its very creation is a byproduct of concerted central bank action, the thing sure sounds like it has to be. As we know only too well since 2008, the financial media will uniformly call these things and the creation of more of them “money printing.” If everyone says…

Not only that, the accounting. One day, there’s little to no bank reserves on the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet, then, seemingly the next, there’s tons of them. Trillions. How can the Fed go from a small (or smaller) amount to a much bigger amount without that being a noteworthy monetary event?

Easy. The perspective is all wrong. If you begin with the central bank, then it certainly looks like a huge, massive, inflationary increase in money supply. And we can’t forget how we are all taught from the very beginning to anchor our monetary perception with that central bank at its center.

A large-scale asset purchase (LSAP), those programs like QE which increase the Fed’s balance sheet, analyzed instead from the more appropriate standpoint of the banking system ends up seeing bank reserves very differently. Even the Federal Reserve’s vast staff of academic accountants know this (unfortunately, many perhaps most of the FOMC’s voting members themselves appear to have no idea what’s going on when it comes to QE’s and LSAP’s).

Bank reserves are nothing more than the byproduct of a central bank doing something. That’s it. Even when we extend our view to what banks do in response, it isn’t what they are supposed to, either.

But since the central bankers want you to think inflationary and only inflationary – because, let’s face it, the reason they are conducting one or more QE’s in the first place is because conditions are threatening deflationary – they are quite content to sit back and let the financial media spread the lies and misinformation on their behalf. Officials judge this distortion to be on the one hand harmless, while on the other more than helpful (in theory).

Monetary authorities see this is a little white lie told for your benefit, therefore harmless. And it’s helpful to the official cause because it reinforces the myth that central banks are money printing goliaths, and that what they do with these QE’s could only be tantamount to inflationary excess – if not some reckless extreme.

If it had been or still is money printing, why, always and every time, the need for more and bigger?

The credibly promise to be irresponsible just isn’t so credible. You can never forget about the rest of the zoo. Here’s why.

Let’s go through the accounting, and then afterward we’ll actually check our work with real data; the Federal Reserve’s data, no less (and you could just as easily use bank balance sheet reports filed with the SEC).

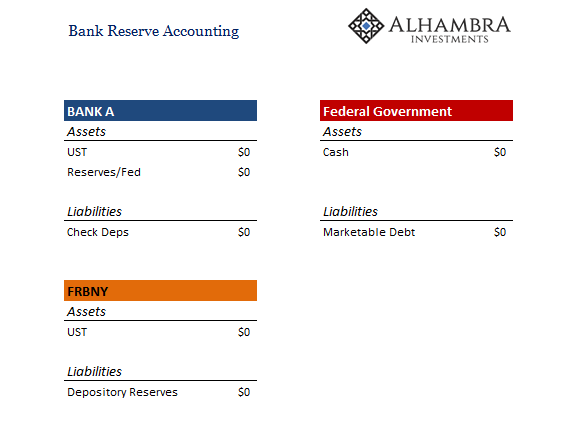

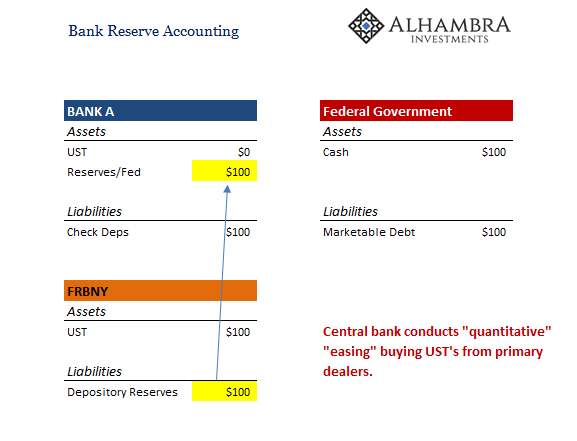

Here we start with a simple bank model. Bank A is our primary dealer, the federal government is the federal government, and FRBNY the Fed’s primary branch agent which puts the large in LSAP.

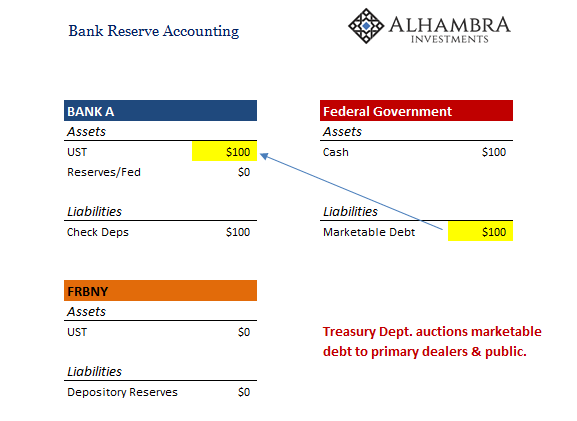

The federal government, as it always does, wishes to sell marketable debt to the public. It conducts an auction. These happen regularly, meaning the real world is obviously more complicated, but our simple example here will more than suffice for illustrative purposes.

The Treasury Department creates a bill, bond, or note depending upon various factors put together from conversations with primary dealers like Bank A as to both public as well as bank appetite and to what terms the debt offerings might reasonably satisfy them.

The UST becomes a liability for the government and after auction it is now in the hands of Bank A (above).

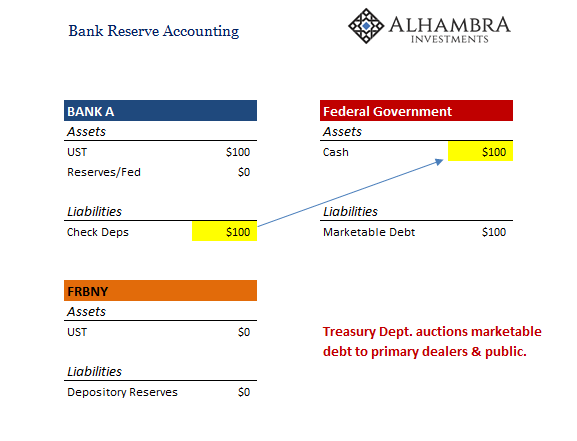

At the same time, Bank A has created a checkable deposit balance for the Treasury Department (in reality, adds to the one which has existed since the primary dealer became a primary dealer). Against this bank liability, the government now has the same amount in cash (above).

Notice who actually creates what sort of monetary form, keeping in mind there are many more that make up the zoo – no bank reserves are required, nor were they ever necessary. That’s why up until 2008, there really weren’t any (nor were there much by way of checkable deposits, again the zoo).

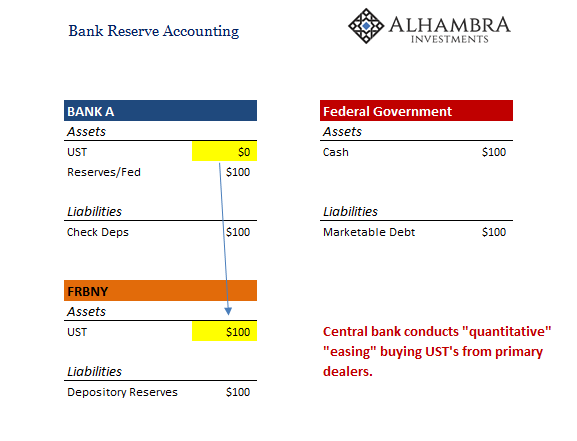

The Federal Reserve, however, for “inflationary” policy reasons that have everything to do with the Zero Lower Bound (ZLB) rather than “money printing”, it decides to expand its balance sheet therefore it has to conduct an LSAP. All that means is the central bank has to buy an asset from the banks legally authorized to do business in this manner; primary dealers.

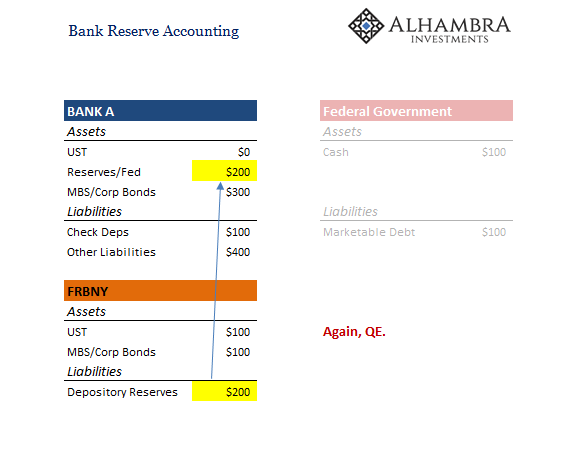

FRBNY purchases the UST from Bank A (above).

On the Fed’s books, the increase in asset becomes an increase in liabilities called bank reserves. That is credited as an asset in the name of the primary dealer doing the selling (above).

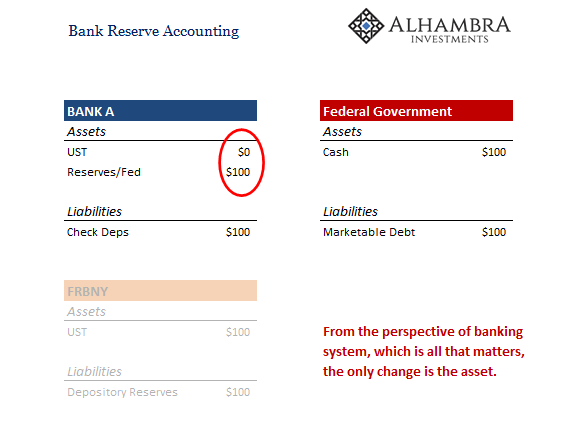

It becomes confusing only because people are taught and told over and over to look at things from the central bank perspective; and when you do that it really looks like the Fed has “added” something.

However, if you correctly view the system from the banking system perspective you realize instead that the only thing which changed was the asset the bank ends up holding – swapping a UST, in this case, for a reserve balance (above).

That’s it!

Where this is all supposed to become inflationary is in how the public (and even banks) interprets, is led to interpret, these convoluted and mostly hidden or at least opaque activities; not from the money itself, because there isn’t any! The bank, not the central bank, created the money to start with.

What matters is what banks do, including what and why they might do something with their own liabilities.

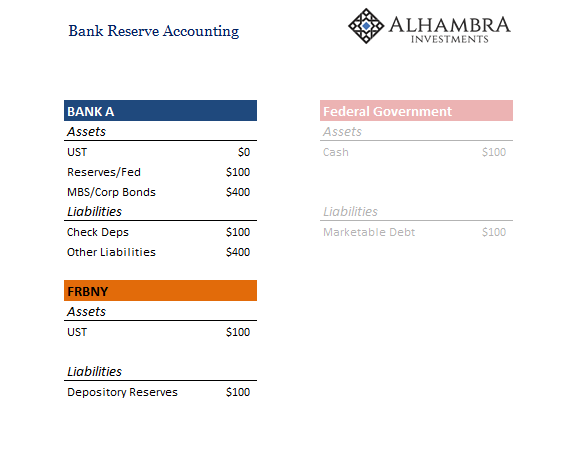

That in mind, we extend our QE-type scenario to where it might begin with existing bank holdings on its books. In this one, the true nature of QE’s asset swap becomes more pronounced.

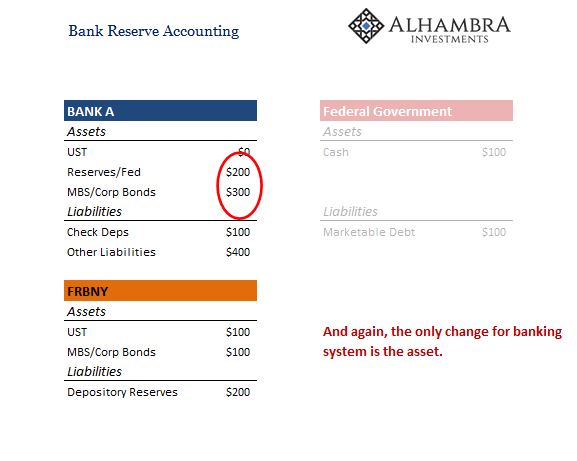

Here we have Bank A with the same transactions still on its books as our earlier example, only now we’ll also assume it already held $400 in various other assets for which it had already created (or borrowed them from some other counterparty) $400 in various liabilities. QE in this case is exactly the same as it was in the first example. FRBNY buys an asset from Bank A, the primary dealer (above). In return, Bank A is credited with more bank reserves (below).

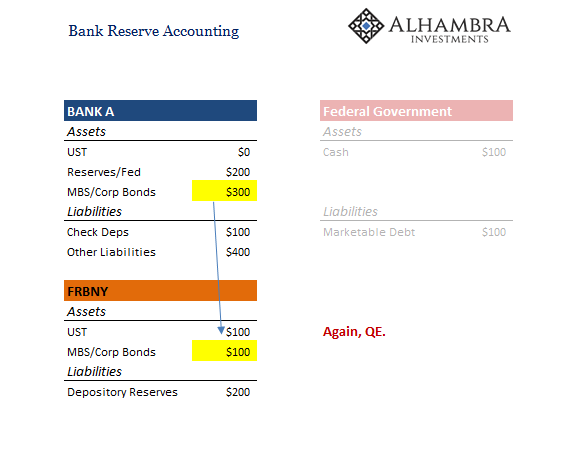

QE in this case is exactly the same as it was in the first example. FRBNY buys an asset from Bank A, the primary dealer (above). In return, Bank A is credited with more bank reserves (below).

From the banking system’s perspective, as before, the only change is in the composition of assets. The deposit or bank liability creation is done before QE ever showed up (below). Bank A had $500 in total liabilities before, and it finishes with the same $500 in total liabilities afterward.

From the banking system’s perspective, as before, the only change is in the composition of assets. The deposit or bank liability creation is done before QE ever showed up (below). Bank A had $500 in total liabilities before, and it finishes with the same $500 in total liabilities afterward.

So we know, without a single doubt, QE does not create money; banks do that.

Would it matter if they did so, however, at the behest of an LSAP or QE? If bank reserves aren’t money, and they aren’t, what are all these checkable deposits?

This has become a more common fallback position for many who see and appreciate the accounting but who aren’t yet ready to let go of the classic money worldview with the central bank at its center. Maybe bank reserves aren’t money, but, go back to our first example, perhaps the Fed gets banks to create money on its behalf when it announces its intentions to do QE.

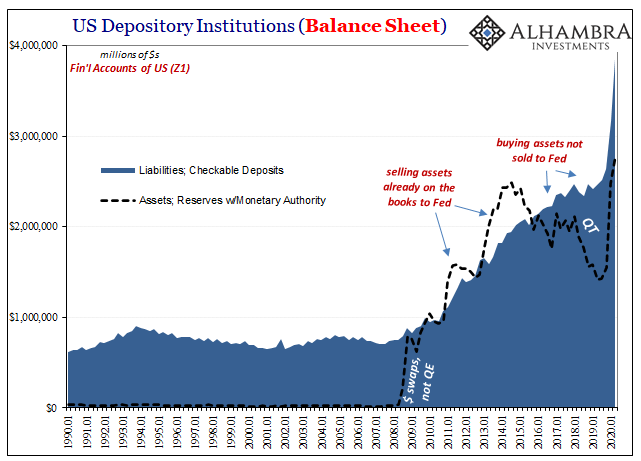

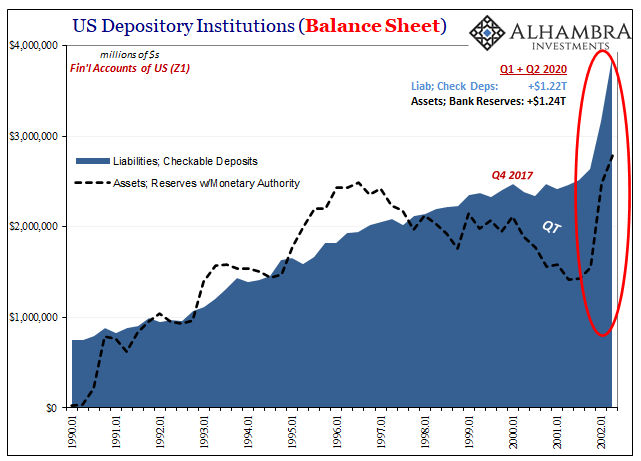

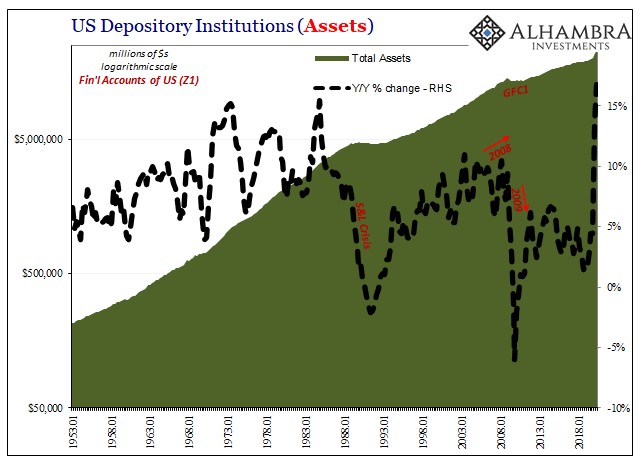

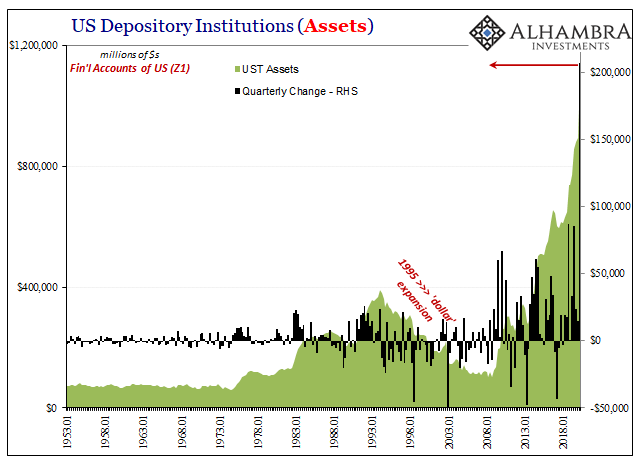

What I’m showing you here (above, below) are all figures published by the Federal Reserve. In its Financial Accounts of the United States (Z1), the central bank aggregates all the balances reported to it, and surveyed from, in this case the nation’s depository institutions (and there are only depository institutions nowadays, all the formerly “commercial banks” converted during GFC1; the Z1 used to report these separately, which was extremely helpful, but since there’s only the one type of bank there’s now only the one series of bank data).

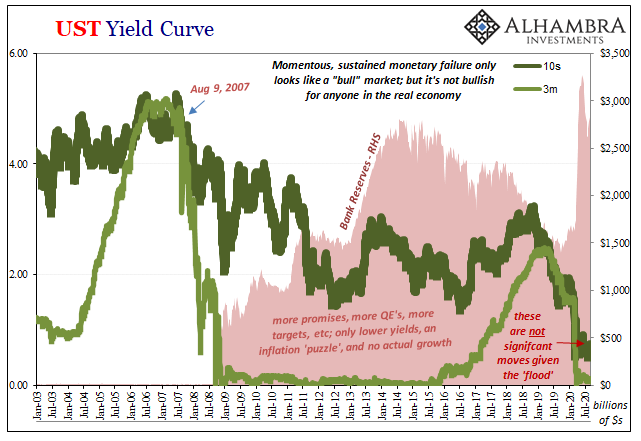

Above in blue is the aggregate level of checkable deposits (liabilities) for all US depositories (including US-based subs of foreign parents; something that doesn’t matter for us here but sure does elsewhere). The dotted black line is the quarterly reported balances of outstanding bank reserves (assets). There’s a pretty clear relationship.

With the introduction of QE’s, the level of aggregate checkable deposits began to increase for the first time in decades.

In the most recent couple of quarters, notice how the latest QE’s, including Q1 2020’s not-QE preceding QE6 in Q2 2020, are a near perfect match: +$1.22 trillion increase in checkable deposit liabilities against +$1.24 trillion in bank reserve assets. Banks created the former before swapping the asset they used the liabilities to purchase to FRBNY during QE gaining the latter.

QE itself was just an asset swap, but did it make banks create money the Fed can’t?

Checkable deposits, but for who?

We aren’t seeing the whole picture, one that is more complicated as we try to evaluate what the banking system might be up to.

For example, while the balance of checkable deposits was increasing rapidly during GFC1, the balance of federal funds and repo liabilities was falling – by an almost equal amount (between Q1 2008 and Q2 2009, +$139.9 billion checkable deposits against -$134.9 billion repo/fed funds). Banks created deposit money for the government, while at the same time getting the hell out of shadow money arrangements.

And that makes sense! The end result of a shadow money arrangement had left formerly commercial banks with a ridiculously shaky proposition (owing money in repo on crap collateral, for instance). QE offered a much safer alternative where at the end of it the primary dealer created a stable deposit liability (with the federal government) offsetting the bank now holding one of the least risky assets (bank reserves).

Repo MBS vs. checkable deposit. No contest. Plus, with the latter, the bank would end up with a choice of holding UST’s or bank reserves (to QE, or not QE – depends upon repo collateral!), both liquid and bulletproof. De-risking on both sides of the balance sheet.

In fact, banks wanted to do as much as they could to offset tremendous risks they might not have been able to rid themselves of.

So even if bank deposits (checkable deposits, in this case) increased during the crisis, these were not deposits held by the public nor were they intended to create more money and credit for the public (or the shadows). It was more deposits in the hands of the government which banks used to help themselves thoroughly de-risk their balance sheets.

Though the aggregate level increased, the mix of monetary forms (the whole zoo) continued to favor less usable, less used, and less effective money.

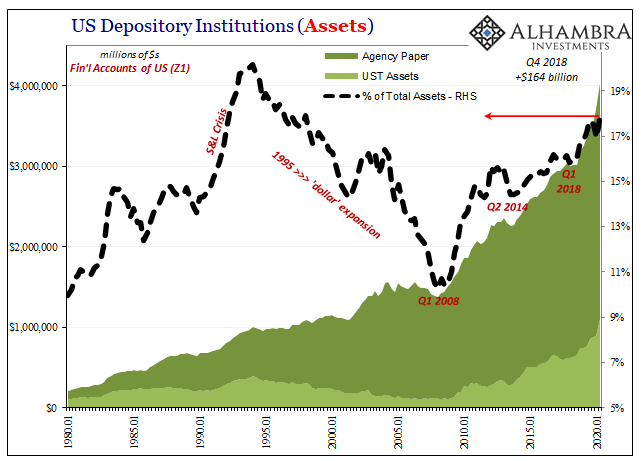

In fact, during the worst parts of GFC1, there had been enough of this asset swap/checkable deposit activity that bank assets overall continued to increase – as did overall liabilities (because the one has to balance the other). But that only masked this massive, and ultimately deflationary, rotation of bank assets (and liabilities) toward more safe classes (including bank reserves) while purposefully avoiding (for a very long time) the risky assets (like loans) the economy needed to expand.

It wasn’t until later in 2009 when the big balance sheet purge finally showed up. Once the banking system had added enough safe assets including a huge dose of Treasuries (for repo), then they took the axe to their balance sheets.

And that was the opposite of what QE was supposed to have accomplished. It’s fancy name is portfolio rebalancing, the belief that banks will be thoroughly impressed by their interpretation of central bank policy – because banks know the accounting they sure aren’t going to be impressed by all this asset (and liability) swapping alone.

But, as noted above, and as you’ll see below, as well as any survey of the mainstream literature, banks never do this. To the contrary, they end up de-risking both sides of their balance sheets in lieu of portfolio effects. We’ve seen this everywhere QE happens, including places like Japan and Europe even when a penalty has been added to holding bank reserve assets (called NIRP).

Banks consistently choose de-risking. Everywhere. Every time.

In fact, this lack of portfolio rebalancing had been evident right from the beginning. I wrote last month about the first big study conducted in 2005 by the Bank of Japan in the aftermath of its first two QE’s where bank activities post-asset swap had been concerned:

The other major theoretical channel for QE is called rebalancing, or portfolio effects. This is where because the central bank is buying government bonds as well as handing out what people say is free money, the banking system itself then uses all this free money to go out and buy risky securities or to engage in lending to replace lost income streams scarfed up under BoJ bond buying.

And in the paper the rebalancing effect “has not been found to be significant”, either. What Japanese banks did do is repurchase more of the same safe, highly liquid government bonds.

Yeah, exactly what American and European banks have done, too. Both sides, assets and liabilities.

OK, to sum up: QE doesn’t create money, banks do. Ultimately, bank behavior is the key to success, which we can observe from both the asset as well as liability side. Even when the banking system is creating additional checkable deposits, even when those checkable deposits are an indirect byproduct of QE inducement, that’s only the beginning not the end of the story.

Like QE itself, these are just transactions moving ledger balances from one perception to another often without regard or full account of the shadow money transactions (the whole zoo, and so much destruction of it) that provoked the QE response in the first place. It is what banks do and why they are doing it, not what the central bank does.

If the banking system is content at creating checkable deposits for the government, it’s not inflationary, either, because banks must not be interested in the rest of the zoo, shunning rebalancing into risky activities like credit, lending, or replacing lost shadow money globally.

In fact, the more you see these risk-less types on both balance sheet sides go up, bank reserves like checkable deposits, the less inflationary you should be thinking. When you see the Fed’s balance sheet expand, that’s not a good sign. Neither is it one when banks are only interested in creating deposits for the feds.

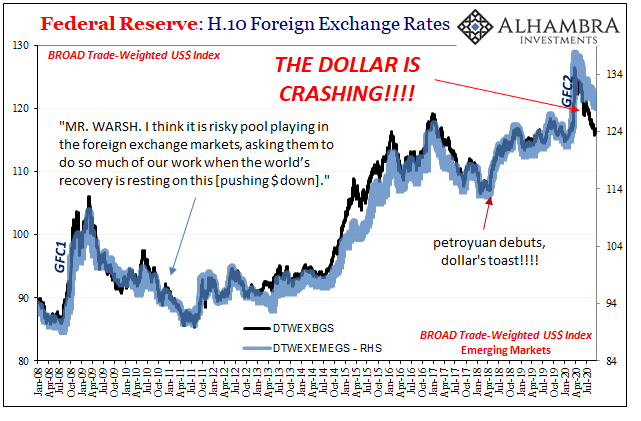

That’s why even the Fed has admitted it can no longer use the word “transitory” despite five previous QE’s (including the fourth begun separately from the third, targeting a different asset class, at the end of 2012; and the fifth which is what 2019’s not-QE actually was). These had already failed to bring about enough small inflation just to meet its own explicit (and explicitly symmetric) mandate even though each and every QE was met with mainstream interpretations of horror and disgust leading to so many constant forecasts of dollar like Treasury market crashes.

Instead, only consistent indications of the opposite disinflationary monetary case. Size doesn’t matter; only bank risk does.

Checkable deposit like bank reserve numbers in 2020 are even bigger again, but that just means more asset swaps – not different asset swaps – and more thorough de-risking not re-risking. Like Japan’s QQE, which was supposed to the awesome-ist monetary program ever, now in its eighth year, why would we expect different results?

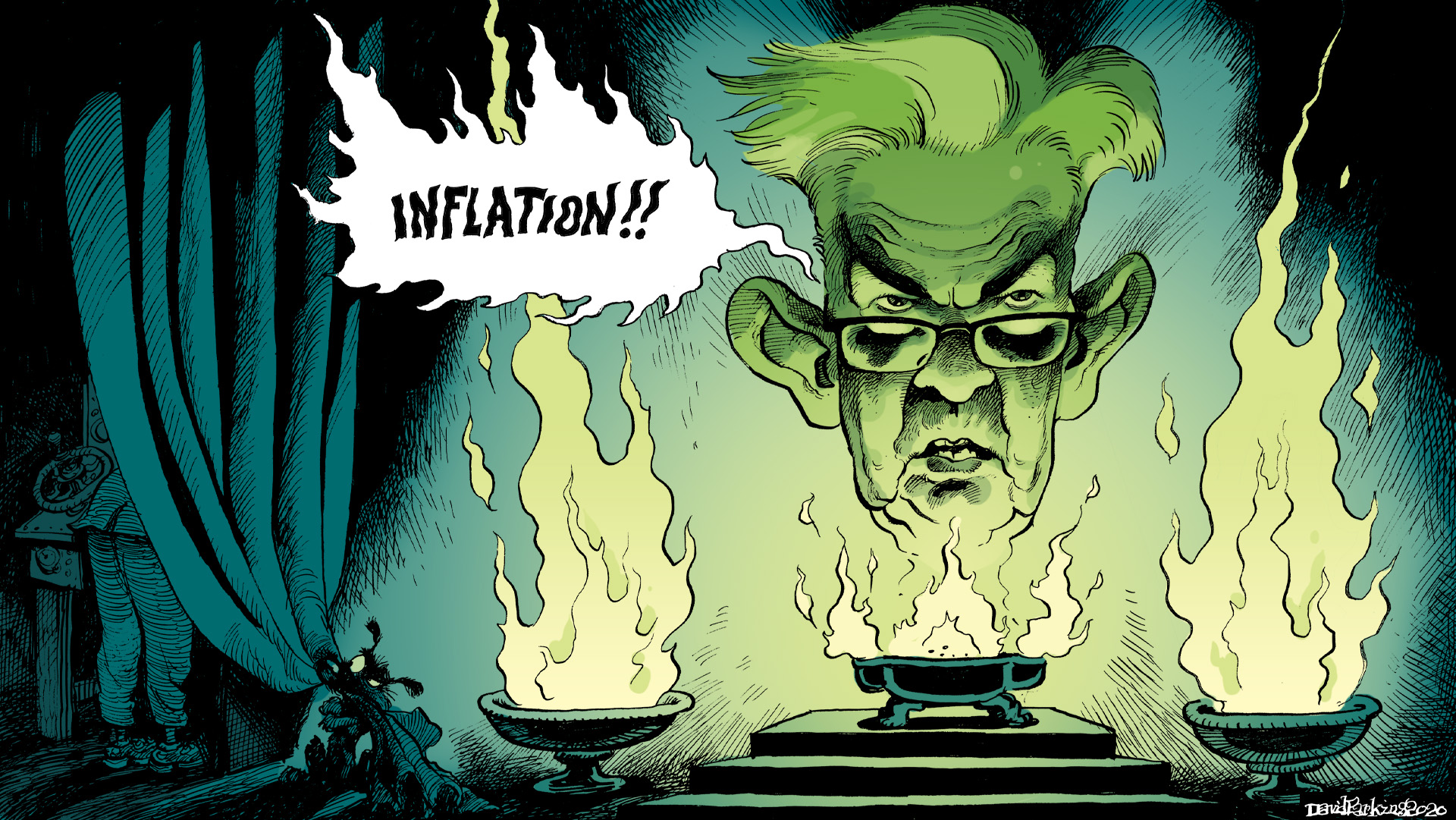

The (bond) markets obviously aren’t, because the credible promise to be irresponsible just isn’t credible. What you can see is only part of it. When you look at the accounting, I think it does help to see why; you peer behind the curtain, realizing the Great Oz is nothing more than a silly little man hoping to impress you so much you won’t bother ever doing the math.

Stay In Touch