COVID-19 is a 2020 story and not so much one for 2021. Pretty much everyone, however, will be seeking to make it that way. To begin this week a stark reminder of that promise: vaccine-phoria. While that unleashed a curiously narrow risk and reflation frenzy, the fact that it wasn’t more widespread speaks to this disparity.

A vaccine doesn’t really change all that much over the intermediate term. An unquestionable good for public health (whatever that means) and a positive development given the circumstances, the world was on track to achieving herd immunity anyway (if it hasn’t already). Not only that, given how even a “fast tracked” vaccine is more than a year away from full production, we’d have hit herd immunity long before.

Instead, the problems which will define next year began in the middle of this year. Not case counts and certainly not death rolls (which aren’t spiking). The economic factors which have been underlying the non-economic portion of the rebound this entire time have been coming to light.

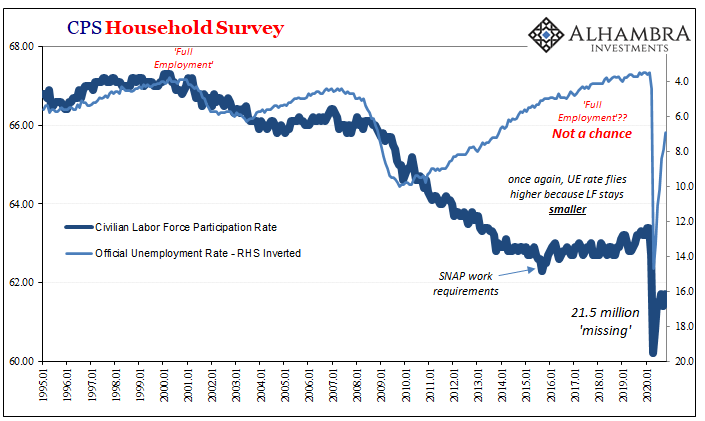

Those in the labor market most of all.

Where jobs and employment have been concerned, it has become more concerning that there hasn’t been more here.

While it was good that last week’s regularly-scheduled FOMC meeting received less attention than usual, unfortunately this was only because of so many other distractions rather than a healthier trend toward acknowledging its irrelevance. But with COVID to blame this time, central bankers have become a bit more forthcoming than they usually have been.

Not only that, having made a (partial) confession about the lack of full recovery the last time (inflation puzzle) it’s interesting how monetary policymakers are sounding so much less resolute about what they do when compared to days gone by. QE used to be the greatest thing ever, but now:

All of us lived through the experience of the years after the global financial crisis, and for a number of years, there in the middle of the recovery, fiscal policy was pretty tight. I think we’ll have a stronger recovery if we can just get at least some more fiscal support.

Cowards. The above is what the Federal Reserve’s Chairman had to say last week at his press conference following a policy decision and statement whereby the Federal Reserve isn’t as optimistic as you know it really, really wants to be. The last recovery wasn’t great – or even a recovery – but it’s not their fault, they say. Blame “austerity.” Convenient.

Not only does it rewrite the QE history, it’s even more convenient given where things stand right now. While in some places it might seem like where things stand is incredibly good, not even Jay Powell is willing to say so. Thus, his plea for more fiscal “stimulus.”

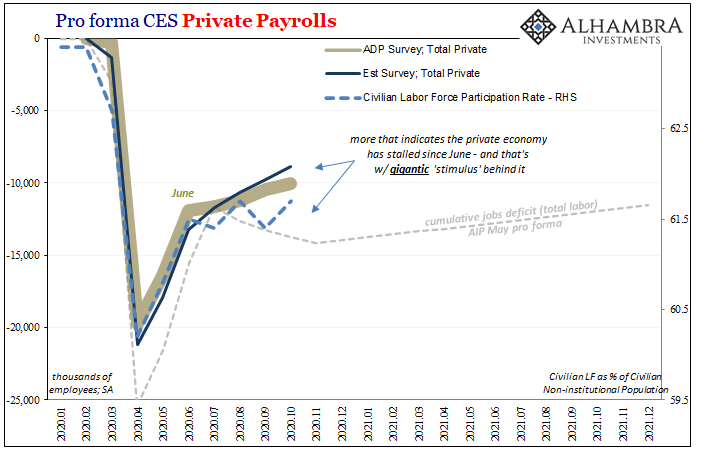

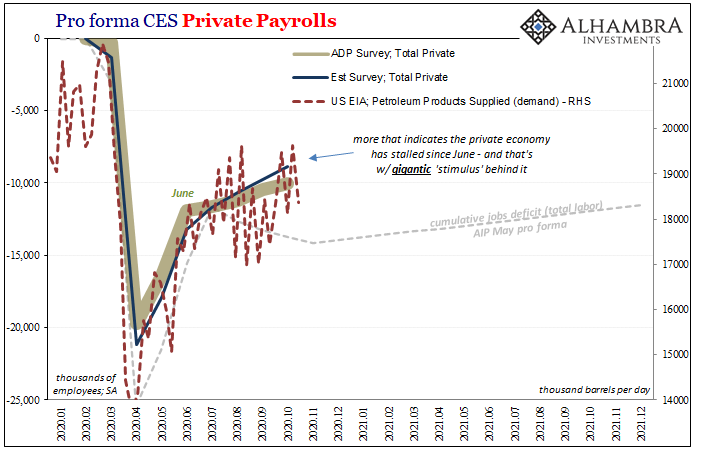

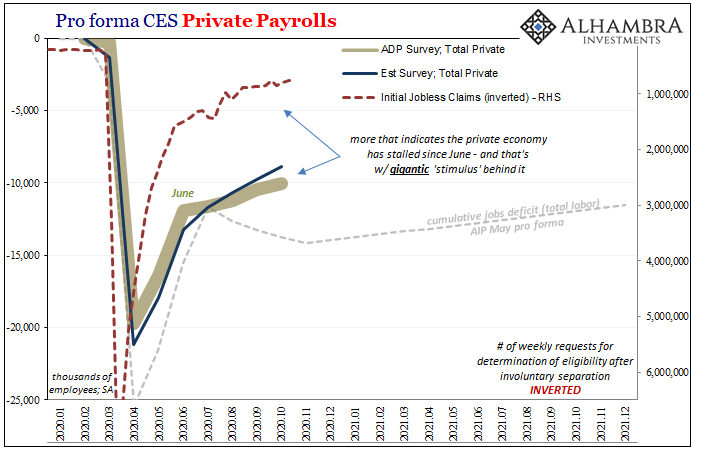

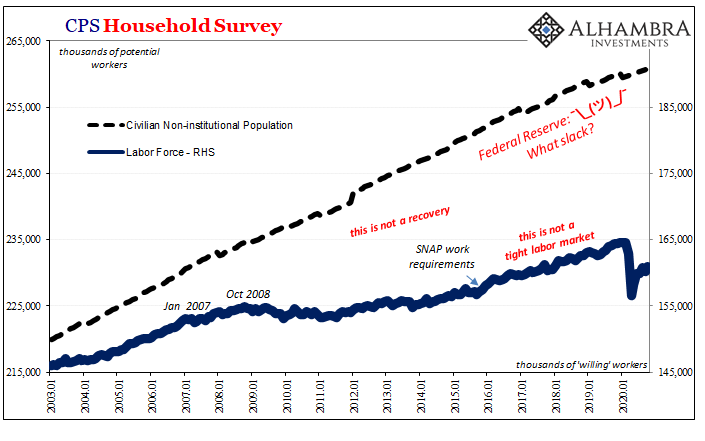

In particular, the main emphasis for the economy, as Powell said, is “a long way from our goals, and we’re halfway there on the labor market recovery, at best.” Halfway is putting it charitably because it had been the initial rebound euphoria which got it that far on its own (no thanks to Jay’s QE) but now seems to have stalled.

While last week’s drop in the unemployment rate skewed the narrative, the rest of the BLS labor data showed that something has been different in the rebound since June. That’s not a COVID second wave; it’s the economic damage done to the economy becoming more evident as the initial stage euphoria fades. Though QE was sold as one, there actually is no policy vaccine against such emerging second and third order effects.

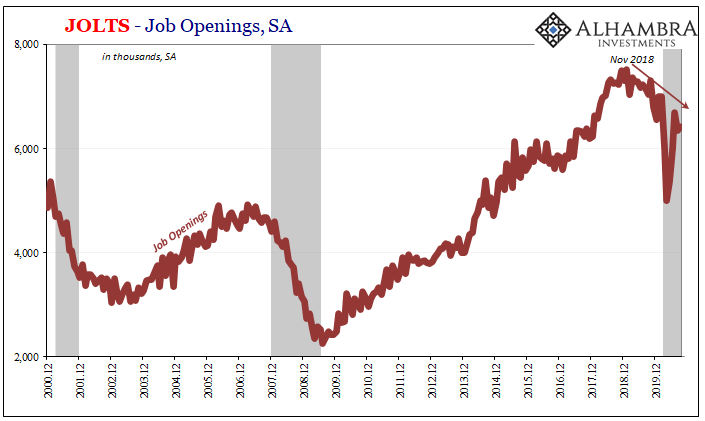

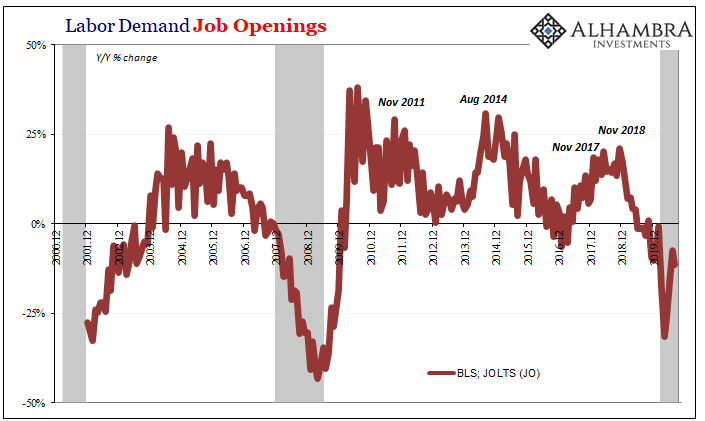

Today, the BLS provides more evidence, the JOLTS series, testifying to this. First up in them was an absolute favorite amongst US central bankers for a very long time. Going back to 2014 when Job Openings surged and Janet Yellen pointed to it as confirmation of inflationary recovery she was sure was for sure by 2015, like the unemployment rate it has remained as one of the few policymakers could lean on for all those years since 2014 when the recovery and inflation failed to show up.

Now:

If JO was your go-to picture of economic strength (when there wasn’t any), look at it now especially in the context of 2020 and “we’re halfway on the labor market recovery, at best.” The lack of rebound in this particular measure of labor demand remains its defining feature when it really should have been exploding upward.

The first “V” is dead. This is now the second attempt, notably being led by Jay Fiscal Cheerleader Powell.

Not only has that rebound come up well short of February, it’s even that much shorter from November 2018 (landmine) when this current downturn had actually begun (not COVID, either). More to the point, these things all related, the number of estimated Job Openings has declined slightly since…July.

Stall.

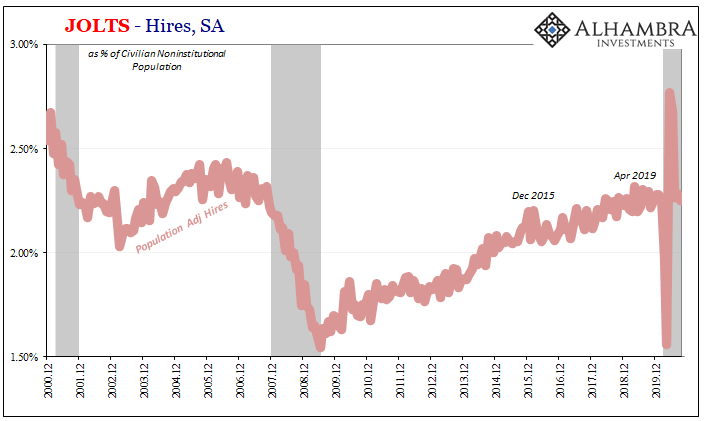

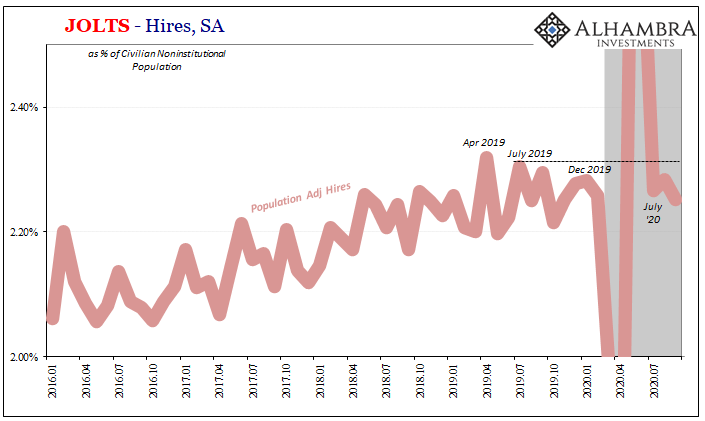

And that’s not all. Perhaps even more important, so far as the JOLTS data might be concerned, hiring activity (HI) is only sideways, too, and moving along at an appreciably lower level than the economy needs. The rebound got off to a good start, but then…?

After spiking in both May and June, as you would expect with businesses ramping back up as the economy reopened, by July the rate of hiring was back down to levels below what they had been last year. Compared to September 2019, hiring in September 2020 (the latest data; JOLTS is one month further behind payrolls) was “somehow” 1.5% less even though the economy of summer 2019 was one on the verge of recession and the economy of summer 2020 is supposed to be charging ahead at full QE-power.

Let’s not forget, too, how much fiscal “stimulus” has already been uncorked and how it only led (arguably) to “halfway.” Chairman Powell, the prime purveyor of that QE power, is in front of the assembled press pleading for more help from Congress; daring its membership to remember how the last “recovery” came up so very short already.

In that sense, it’s kind of a shame that more people aren’t paying attention to last week’s FOMC meeting. Once the unequivocal slayer of all monetary dragons, the Mr. Universe of monetary policies, the Fed now admits it can’t do much without much (a ton) of someone else’s help. How the mighty have fallen; they were never mighty to begin with.

That’s what the economy is saying, too.

Stay In Touch