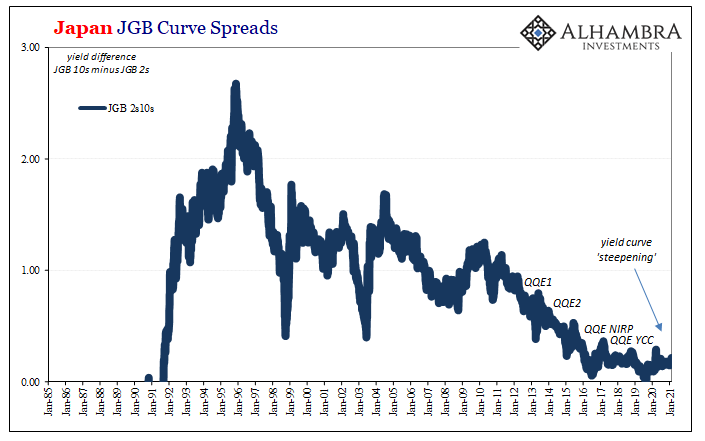

The Aussies weren’t the first to drive into the YCC channel. That “honor” belonged instead where it always does: Japan. The Japanese had also pioneered yield curve control just like they had for practically every single element behind post-crisis monetary policy everywhere else around the world. It’s always a safe bet that if some central bank somewhere starts doing something it has already been tried – and failed – at the Bank of Japan.

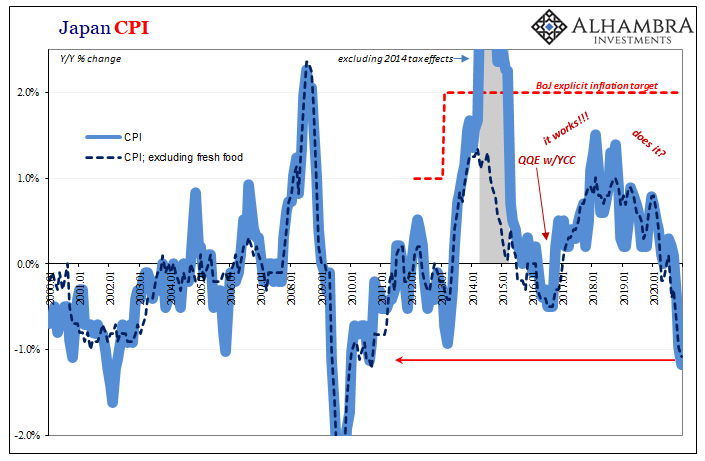

YCC, or yield caps as practiced by the RBA in Australia, has a couple of purposes. The overriding goal is the same as all the other monetary policy “tools”; to bring inflation up to a specified target, or, as in Japan and now the US, to boost inflation and keep it elevated long enough so that it overshoots and averages out for all the many, many years of policy-defying disinflation and deflation.

Where YCC differs from QE is in how policymakers believe the bond market trades. Quantitative easing specifies and even fixes the level (or a range) of monthly bond purchases, whereas yield curve control opts to convert the idea to a fixed interest rate outside of the short end of each curve.

No one can say for sure how much of an impact, say, ¥80 billion a month in gross bond buys spread out across the entire JGB curve might have over the nominal levels of the entire yield curve. While neither Bank of Japan officials nor their global counterparts take heed the words of Richard Fisher (why are we buying bonds the market is already buying?), such uncertainty can and did lead to the situation where the central bank buys huge quantities over the course of several years because QE doesn’t work.

How, then, to keep “stimulus” low rates without being forced to buy nearly every asset on Earth?

Rather than being kept to a promise to purchase specific quantities year after failed year, it was believed that monetary policy could achieve the same immediate goal – low interest rates – by specifying a yield target (or cap). In this YCC case, the central bank only has to buy the amount of bonds necessary to maintain either a target or target range.

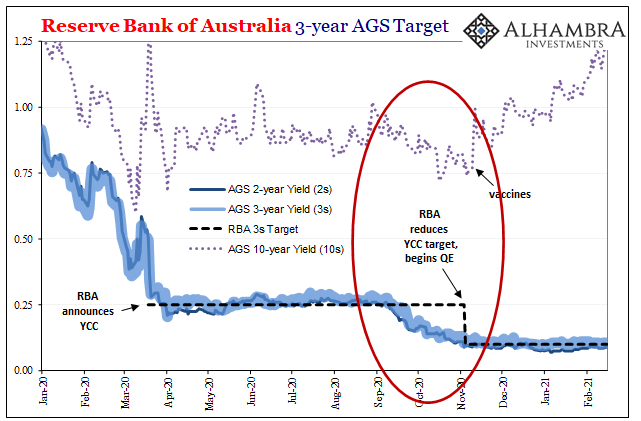

As in Australia’s initial experience, RBA didn’t have to buy any!

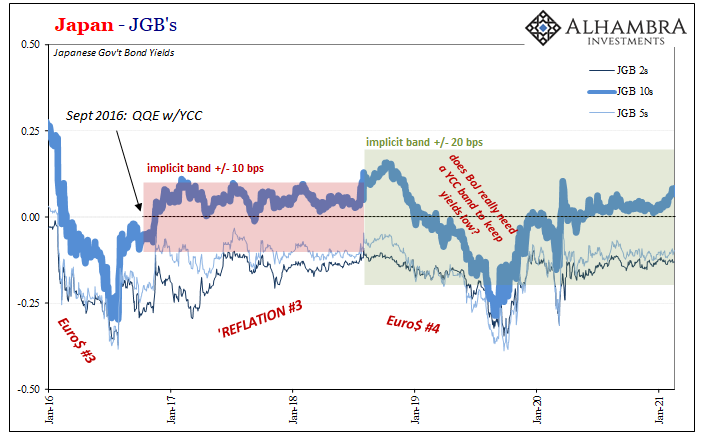

Specifically, the Japanese version of QQE w/YCC (already having been added to QQE2 as well as QQE w/NIRP) says that the 10-year JGB would be held “around” zero yield “until the year-on-year rate of increase in the observed consumer price index exceeds the price stability target of 2 percent and stays above the target in a stable manner.” The market then allowed for an implicit range of +/- 10 bps from that target, which was adjusted to +/- 20 bps at the end of July 2018.

Again, the idea is that low rates are stimulus, and without some monetary policy activity rising rates would rise “too much” and short circuit the recovery before it ever had a chance to get going.

But how long is a “chance to get going?” In the Japanese case, bond yields behaved as BoJ wished, but was that the case of the market unwilling to challenge the top end of the yield range, or, as in the case of Australia 2020, the market not buying into the inflationary recovery scenario and thus, Richard Fisher, there hadn’t been much selling in JGB’s (no BOND ROUT!!!) and rising yields to begin with?

As is also typically the case, US central bankers take a more honest view of Japanese results (before then becoming disingenuous about reviewing their own even when US central bankers follow the Japanese example right down to the smallest details). Just about four years into QQE w/YCC, last year FRBNY’s Liberty Street blog admitted:

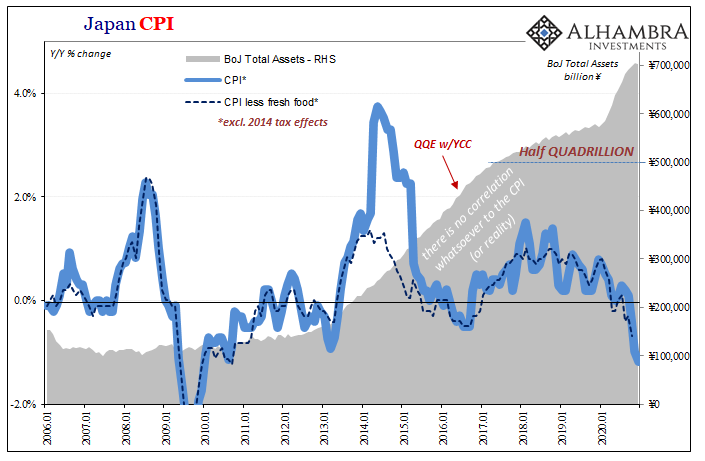

Has YCC been a success? Seemingly not on the inflation front, at least thus far. Core inflation has been running near 0.5 percent in recent months, barely higher than when the policy was adopted.

Despite this, the author desperately tried to give the Japanese an out, claiming that the labor market had grown tight only to be disrupted by COVID in 2020 and therefore not giving wage-driven inflation a full chance to materialize (as if four years later that was still possible). So, the usual standby is deployed:

Of course, we don’t know what inflation would have been without YCC.

In other words, as little inflation as any of these things generated – despite each and every projection claiming otherwise – central bankers will always say that it might have been even less had their monetary policies not stepped in. Always “jobs saved” with these things.

A far more reasonable, logical, and evidence-based explanation is that none of these things have much of an effect – right down to the very basics. Like QQE, or QE, adding YCC only changes the pace or level of asset purchases and doesn’t have much effect on inflation or recovery, and that is why yields trade the way the trade! Such is only inferred; meaning, that policymakers desperately want to attribute low rates to their efforts so as to claim “stimulus” even as nothing ever gets stimulated.

Interpreting the bond market and its yields independently of monetary policies, all of them, we end up realizing instead that low rates aren’t stimulus at all (interest rate fallacy) and can therefore reconcile the real economy and the real-world untangling market reality from repeated failure. In the process, we easily discard these central bank efforts knowing both why and how they are, largely, irrelevant.

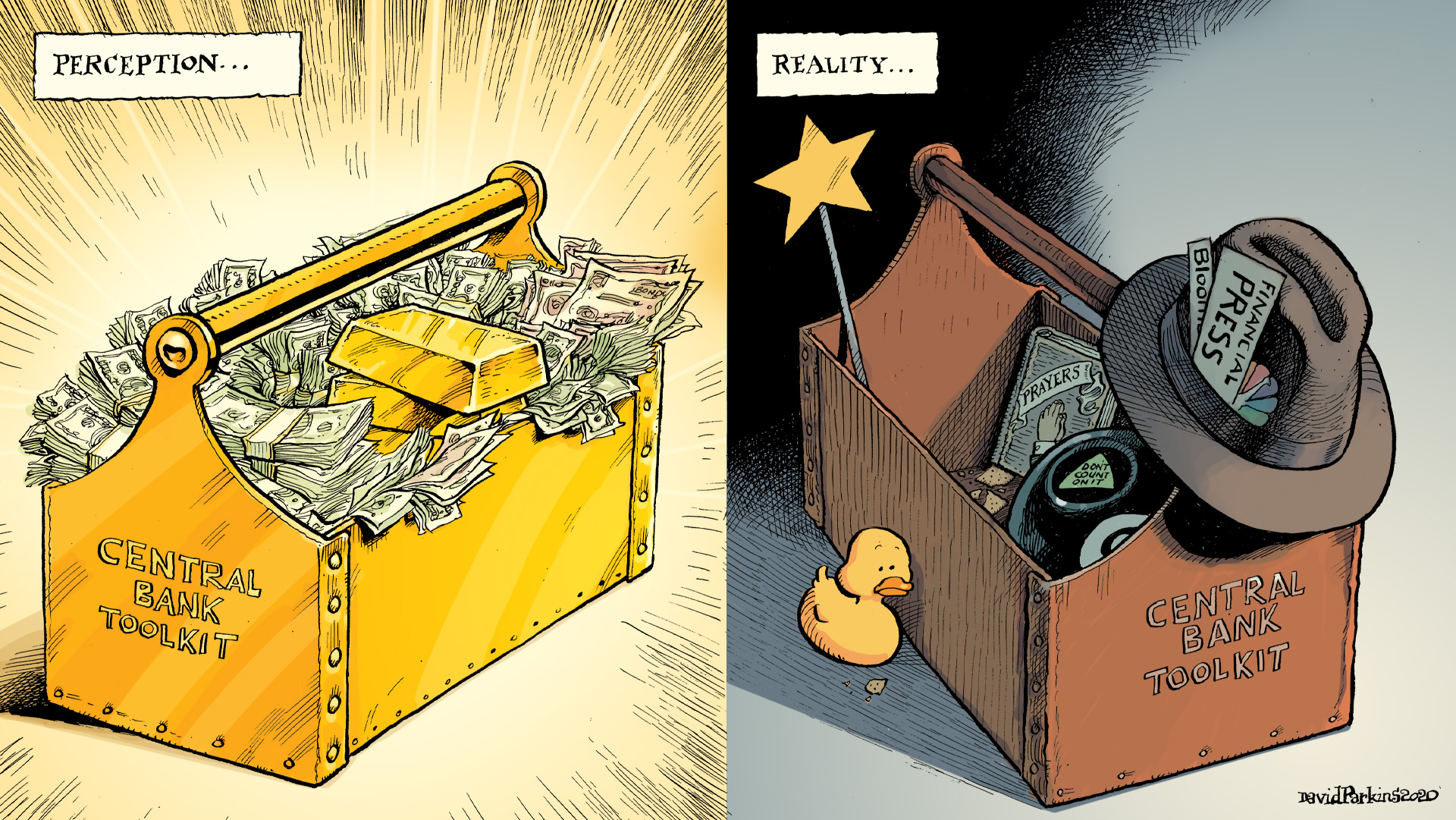

Central bankers say YCC is needed, or will be needed in other jurisdictions, in order to keep yields low long enough. Bond yields, despite the occasional reflationary trend, which never lasts, remain low because bond market participants know how futile and impotent monetary policy actually is – as all the evidence consistently shows – no matter which specific “tool” or tools is pulled out of the homogenized toolkit.

YCC is nothing more than changing a parameter of QE. Since QE doesn’t do much, YCC is therefore equally as ridiculous; including how it is and will be described in the mainstream view. Some people will never believe this, but it is actually only that last part which truly is the whole point.

Stay In Touch