A fascinating and useful bit of economic research was put forward just last month by Britain’s House of Lords (and thanks to Greg for digging it up). That body’s Economic Affairs Committee heard detailed testimony on the subject of Quantitative Easing, commonly known as QE. From the title of the report prepared in advance of the witnesses presenting their opinions and findings (QE: A Dangerous Addiction) you already know they’ve come to the right conclusions if launching from the wrong, textbook approach.

Taking the latter first, money printing and all that nonsense. It is exceedingly difficult to get everyone to realize the contradiction between citing “easy money” as what’s policy and then going through all the plentiful ways (such as Frontline did not long ago) there could not have been easy money.

Small signs of progress, therefore, at least in how even some places around the official and political world there are some visible pockets no longer simply taking QE’s plethora of myths at face value. It has only taken twenty years – even though the very first QE two decades ago was launched under these same questionable assumptions.

I won’t go over all the details of the British efforts here, though many are, again, fascinating in this more scientific affirmative. Instead, the crux of the report comes down, basically, to two parts.

The first is, essentially, “jobs saved”:

The impact of quantitative easing has been subject to growing academic and central bank research. However, there is a recognition across the literature that measuring the effectiveness of quantitative easing is difficult to do with precision. The use of quantitative easing at scale is still relatively new and there are long lags between its deployment and the ability to assess its precise effect. Furthermore, the counterfactual—what would the effect have been if quantitative easing had not been deployed—is difficult to establish.

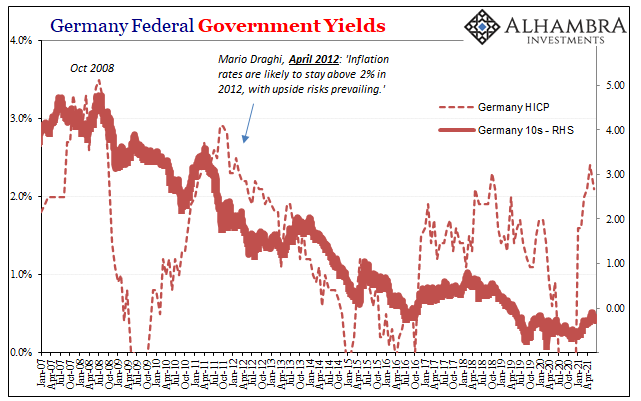

If QE hadn’t been done, maybe it would’ve been much worse. No one can say for certain (but we do have various ways of measuring otherwise, even if Economists and Parliament don’t know about bond yields), so at best no can immediately reject (at least with conventional assessments) the idea that QE didn’t provide some assistance during the world’s darkest hours.

This also a basic summary of how central bank performance last March is being considered (which, again, isn’t really that hard to measure and take apart – if you know where to begin).

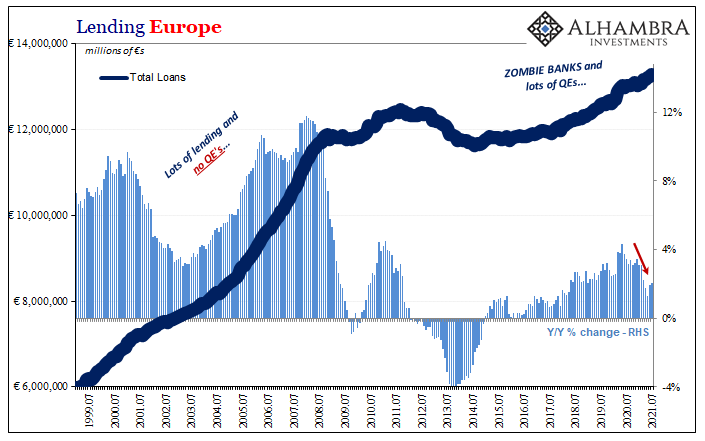

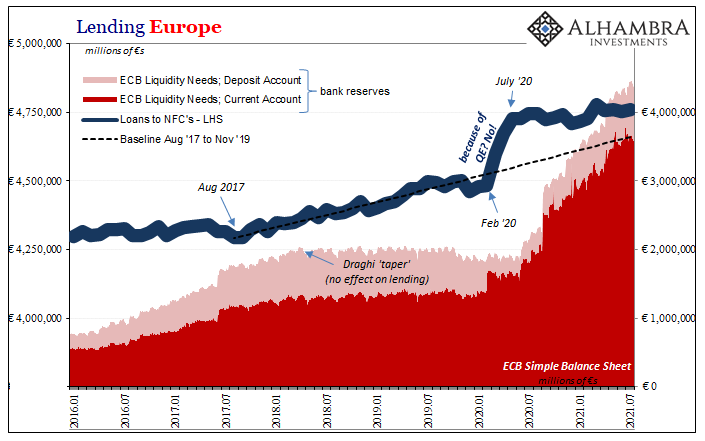

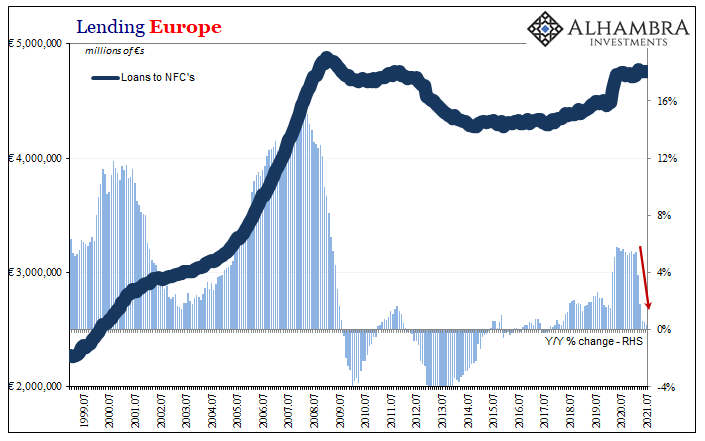

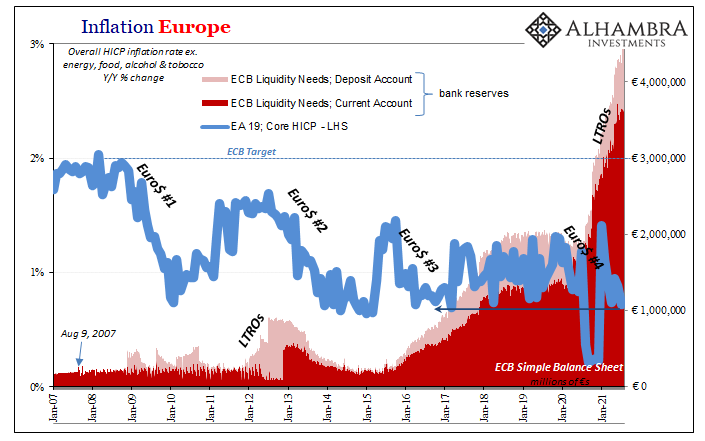

There is, instead, much more confidence as to just how effective QE has been globally in all the various ways it was supposed to have contributed. Lending, inflation, growth, etc. Because these things can be measured and whose measurements are easily understood by layperson and specialist alike, there is this growing confidence as to just how ineffective QE has been globally.

This, rather than the other, is the opinion which is, pardon the pun, gaining currency.

Here’s but one summation which quite perfectly describes what really is not a QE dilemma:

Daniel Gros, Distinguished Fellow at the Centre for European Policy Studies, told us that there is evidence which shows that quantitative easing is “very important” in a crisis when markets are dysfunctional. However, he argued that the overall impact of quantitative easing on the real economy and inflation has been “vastly overestimated.”

In short, QE doesn’t work in anything we can measure but it might work in a “crisis” when counterfactuals don’t allow for it to be falsified under commonly-accepted terms. How’s that for QE science!

However you feel about it, nothing here (or in any real economy) musters up to “pouring trillions of dollars/euros/yen/pounds into the real economy.” No part of this repeated mainstream description is actually true; not a single world other than “trillions.”

Even “jobs saved” is a fiction already discredited outside the convention which views central banks as central banks (again, start with bond yields and you’re golden; also gold).

A big piece of the problem – in fact, most of it – begins with the banking system, the real money globally, and therefore ends QE before it ever begins. After all, even Alan Greenspan in the raging irrationality of the exuberant nineties had warned for his successors as he had for his contemporaries:

Policy rules, at least in a general way, presume some understanding of how economic forces work. Moreover, in effect, they anticipate that key causal connections observed in the past will remain fixed over time, or evolve only very slowly…Another premise behind many rule-based policy prescriptions, however, is that our knowledge of the full workings of the system is quite limited, so that attempts to improve on the results of policy rules will, on average, only make matters worse.

Banks, not central banks, make the money therefore they make the rules. Central bankers haven’t bothered about money or monetary rules since before the eighties; and hadn’t been able to really keep any track or make use since before the mid-sixties.

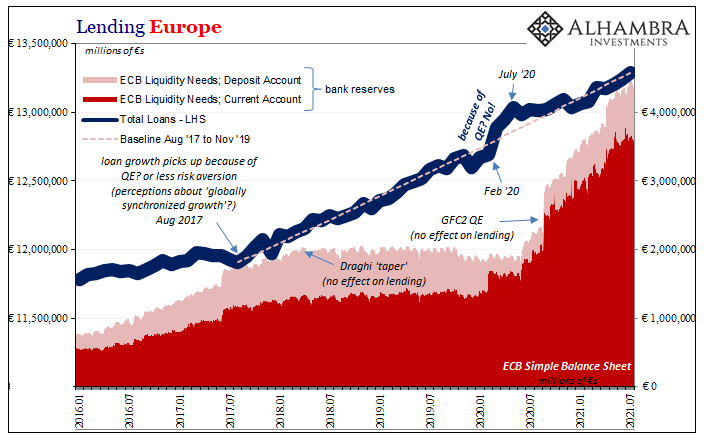

The data I’m adding below isn’t English lending, though it needn’t be (particularly since the House of Lords didn’t limit themselves to examining BoE QE). Without banks, forget the whole thing about “money printing” and any anticipated effects.

Realizing this, the next step (which should’ve been the first step) is to figure out banks. Forget central banks. The system already did a long time ago. Even during its darkest hours.

Twenty years is apparently long enough for the hard-headed to finally start thinking and not just rote reciting myth.

Stay In Touch